By Katharine Moody*

The mothership of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) reform has landed in the form of the Natural and Built Environment (NBA) Bill and the Spatial Planning (SPA) Bill introduced to Parliament last week, reported by interest.co.nz here.

The NBA alone contains 10 parts, 861 sections and 15 schedules. My first thought was, what a nightmare – time to retire.

From an ideological perspective, this mothership is light years away from 1991. Buckle-in for a new horizon. Here are but a few 1991 vs 2022 comparisons.

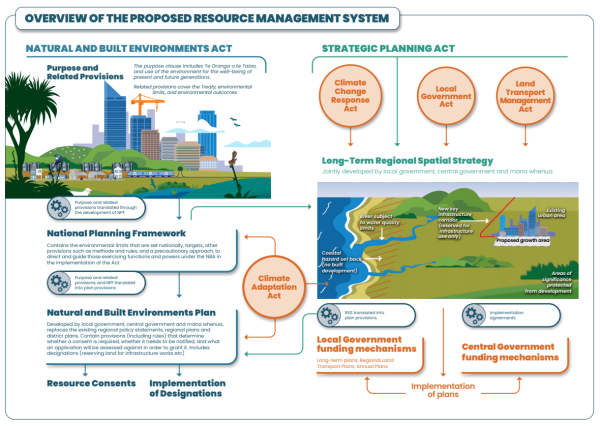

Credit: Heidi O'Callahan (August, 2021). Note: in the above diagram, ‘Strategic Planning Act’ has since been re-named the ‘Spatial Planning Act’

Effects-based vs outcomes-based

The RMA heralded a world-first in introducing an effects-based environmental management regime. This novel ideal seemed to faulter in practice, but its intent on conception was that anyone could propose to do (nearly) anything as an activity, provided that the activity could be shown to either ‘avoid, remedy or mitigate the adverse effects of that activity on the environment’.

In comparison, the NPA is an outcomes-based environmental management regime. In 1991 New Zealand had no environmental reporting regime. Hence, Geoffrey Palmer’s resource management reform group, had no nationally standardised, quantitative understanding of the state of New Zealand’s environment. Since the enactment of a reporting regime in 2015, data collection and

reporting has gone some way to fill this information gap.

The cumulative effects of all the activities are/were not adequately dealt with under the RMA, as each consent applied for has to be considered on its merits - in isolation of the wider implications to the receiving environment on the whole. The NBA with its outcomes-based focus, changes all that.

Sustainable management vs te Oranga o te Taiao

The RMA purpose introduced a uniquely New Zealand legal construct, the concept of sustainable management (not to be confused with the more common globally used concept of sustainable development). The RMA purpose, section 5, goes on to provide a definition of sustainable management, on which this singular purpose of the RMA is based.

The NBA however has a dual mandate, or purpose. The second leg of this dual mandate likewise introduces a uniquely New Zealand legal construct named, te Oranga o te Taiao, literally translated as the health of the environment.

The Randerson Report (the conceptual basis on which the NBA was developed), explains that this new concept was included in the purpose of the Act, with the “…intention is that this will help to promote a shared environmental ethic” (page 75, 115-116). And the Government in its explanatory note on the NBA Bill, tells us that, the new Act;

“…draws on te Oranga o te Taiao, a te ao Māori concept that speaks to the health of the natural environment, the essential relationship between the health of the natural environment and its capacity to sustain life, and the interconnectedness of all parts of the environment.”

This is a somewhat misleading statement by the Government, as the definition of te Oranga o te Taiao (NBA, interpretation) includes an additional ‘limb’ not mentioned above, that being;

te Oranga o te Taiao means—

(a) the health of the natural environment; and

(b) the essential relationship between the health of the natural environment and its capacity

to sustain life; and

(c) the interconnectedness of all parts of the environment; and

(d) the intrinsic relationship between iwi and hapū and te Taiao

This fourth ‘limb’ (clause (d) above) looks to have been latently added to the definition, as it is not mentioned in either the Randerson Report, nor the Government’s explanatory note. I doubt it has been through the same rigour in consideration that other changes to the Act’s purpose have been.

If indeed te Oranga o te Taiao is intended to be a shared environmental ethic, the exclusionary reference to iwi and hapū (as opposed to “people and communities” as per the RMA definition of sustainable management) is a concern that I imagine will be raised in the select committee stage of the Bill’s development.

Bottom up vs top down

The RMA was intended to be a bottom-up form of resource management, with an emphasis on participatory democracy by those living closest to, or most directly affected by, decisions made under the Act. The NBA looks to have reversed that direction, being far more prescriptive ‘from above’.

The NBA confers wide-ranging centralised powers to bureaucratic elites, including iwi and hapū elites in decision-making. It introduces ‘hard’ environmental limits, as either minimum states or maximum pressures on the biophysical environment, via a National Planning Framework. Activities that exceed these limits will be prohibited. And, should an activity fall somewhere between an environmental outcome and an environmental limit, then a set of measurable, time-bound targets will be defined to achieve environmental outcome improvements with respect to the resources concerned over time.

Replacements for district and regional plans, now called natural and built environment plans, must reflect these higher order, directive legislative instruments, and those centrally developed instruments in the lower order plans ‘will reign’. Which leads to the next comparison.

Community planning vs committee planning

Whereas the RMA purpose referred to enabling “people and communities” to provide for their social, economic, and cultural well-being; reference to “people and communities” makes no appearance in the purpose of the NBA.

Natural and built environment plans will not be written by a local council planning department, made up of people living in the communities they serve and answerable to locally elected council members. Instead, they will be written by a new form of statutory authority, called a Regional Planning Committee (RCP). These new statutory bodies will have “…separate legal standing from its

constituent authorities and organisations for the purpose of commencing, or being a party to, or being heard in legal proceedings” (NBA Section 100(4)), including of course, plan development and plan changes.

NBA Schedule 8 describes the provisions relating to membership, support, and operation of these regional planning committees. The composition of these committees is defined in NBA schedule 8(2), and reads;

2 Members

(1) A regional planning committee must comprise at least 6 members, but there is no limit on the total number of members.

(2) Each local authority in the region of the committee may appoint at least 1 member.

(3) Members appointed by a local authority must be appointed in accordance with a composition arrangement in accordance with this schedule.

(4) Iwi authorities and groups that represent hapū must, by a process they determine themselves, set up an iwi and hapū committee for the purpose of determining the Māori appointing body or bodies.

(5) At least 2 members must be appointed by 1 or more Māori appointing bodies of the region.

(6) The responsible Minister may appoint 1 member to participate in the functions of the committee under the Spatial Planning Act 2022.

Closing remarks

There is of course, much water yet to go under the bridge in bringing the new regime to fruition. There are many more comparisons not made here. But, some key questions about the reform that are worth contemplating are;

- Will it demonstrate improving trends in future state of the environment reports on New Zealand’s natural environment?

I think so.

- Will it provide for greater efficiencies and lower costs in realising small scale developments by individual property owners?

I think so.

- Will it make larger scale development more difficult?

I think so, as the parameters for commercial and industrial development will be more constrained by targets and environmental limits. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as constraints can foster greater innovation in design and engineering of activities pursued within the environment.

- Will the mothership ever actually fly?

Good question, as planning is political.

That said, the need to embark on a new horizon of repeal and replacement of the Resource Management Act is one thing all sides of the political spectrum likely agree on. To my mind although the bills look dreadfully cumbersome, they are a basis worth sticking with.

Enunciating a legal framework for the integrated management of buildings, infrastructure and natural resource use, development and protection in a single statute, is a mammoth task. It was in 1991, and so it is in 2022.

*Katharine Moody is a senior tutor at Massey University's College of Humanities and Social Sciences in Palmerston North, who comments on interest.co.nz as "Kate". The views expressed in this article are her own and don't necessarily reflect those of Massey University.

30 Comments

One of the chief problems that I can see from the RMA is that it got hijacked by special interest groups, and a whole industry of paid experts whose interests were served by making it more and more convoluted and difficult. The original act was pretty reasonable if people behaved and administered it reasonably.

These people have not gone away and their motives remain the same. Replacing the act with two mammoth and more complicated acts will only enhance their power to bog down and exploit the system. We can only expect matters to get a whole lot worse.

It is interesting to note that for the rebuild of the Kaikoura state highway the RMA was suspended. The project was executed quickly and with good environmental outcomes.

Yes, that restoration of the state highway is an engineering feat to behold - and I agree with you, it is beautifully sympathetic in design with the environment as well. Although I understand from a student essay written on it that the bicycle path isn't contiguous throughout the route given problems with lack of agreement in that regard associated with the area adjacent to the Mangamaunu surf break. And good point about the suspension of the RMA. So very sensible.

Neither Act achieves - or will - real sustainability. This one appears to facilitate growth (land supply, I heard Parker mention, so help us), so will fall over like the last. And who sets - and monitors - the bottom lines? We don't even do that now...

And your motorway was made of fossil oil, using fossil energy, requires fossil energy to maintain it, and won't be serving the same purpose ex fossil energy (a society running on renewable energy, won't be commuting; to much a waste of energy). Just saying....

I think we're out of time; that this and many other initiatives (some laudable, like Onslow, some pointless like stadiums) won't see the light of day.

All kinds of new monitoring provisions - and huge jumps in maximum penalties regarding non-compliance/fines. New enforcement tool as well, 'monetary benefit orders' - break a rule and make a financial gain - the Courts will have that in addition to your fine, thanks.

Not out-of-time - in the sense that human civilization perishes altogether - unless hit by an asteroid or some such event. Society will run out-of-fossil energy - I'm with you on that one. All the more reason we need to be able to triage fast and in an less bureaucratic way. The new Regional Spatial Plans will sort out infrastructure consenting issues, new provision for 'route protection' and I imagine spatial plans could designate areas for managed retreat too. I'm with you, if it's going to get built, the sooner the better. NZ-scale mega-projects, like the Gully motorway and/or Onslow are going to be a thing of the past for those in the future (hence, my thought build it now or forever hold your peace - lol). NZ simply won't be a 'wealthy' country. I just hope it remains sovereign :-).

Where resource allocation is concerned, first-in-first-served is gone. Some decisions on allocation will be merits-based by bureaucratic elites (i.e., use of centralised powers), others will be market-based allocations. Three principles/tests in the allocation criteria: sustainability, efficiency and equity.

Consents no longer the 'bankable' sort of thing they seem to be presently - new provisions for review and cancellation.

Yes and the bill only requires that the future is not compromised, just a rollover from the RMA. How underwhelming is that?

Well, don't necessarily disagree - but I'm always keen to explore other options!

So instead of the purpose of the Act being:

The purpose of this Act is to—

(a) enable the use, development, and protection of the environment in a way that—

(i) supports the well-being of present generations without compromising the well-being of future generations; and

(ii) promotes outcomes for the benefit of the environment; and

(iii) complies with environmental limits and their associated targets; and

(iv) manages adverse effects; and

(b) recognise and uphold te Oranga o te Taiao.

What kind of language would you prefer?

For example:

The purpose of this Act is to achieve national self-sufficiency, through -

(a) reversing degradation of the natural environment

(b) reducing energy consumption

(c) building accommodation for all

(d) producing sufficient food for all

Just a thought-exercise, but I'm really interested in what you might both see as an ideal aspiration given the need for transformational change, if indeed that's what you think necessary..

Yep something along those kinds of lines

I don’t share the same level of positivity Kate.

The purpose of the NBA is incoherent. The bill is a mish mash of the RMA and ‘new additions’. What I find especially incoherent is the attempt to move more towards an ‘outcomes approach’ but there is still so much clinging to the RMA effects-based approach.

There is nothing on urban design and amenity and I am sure that is intentional. If one cares solely about the quantity of housing rather than the quality of housing then I guess that will be welcomed.

And good luck to planners having to grapple with the public notification assessment tests in the Bill!!!

I was looking forward to your comment, HM. I can tell you've got a lot of knowledge and experience, so really appreciate your views and oipinions. You are right about the provisions that cling to the effects-based approach and, yes, much detail was just a cut and paste. However, I'm hoping that far, far, far fewer consents will be required in the urban development environment under the new framework. I'm guessing (hoping) for example, that a granny flat; a home extension; tree removal and all such minor improvements - including subdivision from one lot to two - will all be permitted activities under the new regime. No resource consents needed (yeeeha) - only Building Act permits. And of course, going from single unit to multi-unit will be included in that. So, I see lots of potential upside for small owner-initiated urban development. My positivity coming through, of course.

Yes, I imagine the lack of urban design and amenity is intentional. And I'm far more liberal in my thinking on that. I quite like this ideological approach;

https://marketurbanism.com/2017/03/29/towards-a-liberal-approach-to-urban-form/

If one wants a more prescriptive type of amenity - there are communities such as Whitby with amenity managed collectively by the village administration. I don't see these sort of neighbourhoods necessarily being impacted upon by the new regime. That said, I don't like restrictive covenants that push up dwelling build-costs.

For me personally, I like more organic neighbourhoods - and the more quirky and spontaneous 'sense of place' they afford. That's why I'm a Wellingtonian - that city is generally not 'predictable' or orderly.

I only briefly had a look at the public notifications criteria - but I understand they are far more complex at this stage. I did note the phrase "relevant concerns of the community" - very fuzzy, But, take for example the limited notification decision by the KCDC to erect a large multi-use structure on the Paraparaumu open space beachfront. It should have been publicly notified for exactly that kind of reason - a 3000-signature petition against the proposed design once publicly released. So, yes, swings and round-abouts and (I hope) legal wording can be improved. My experience of how "affected party" is currently applied/determined is very dubious. If we applied a 'reasonable person' test/approach to affected parties and notification, that would be far superior to my mind.

I wanted something far more black and white on notification, Kate. Eg. All discretionary activities automatically notified, everything else non-notified.

There’s a huge amount of unproductive wastage in the system in terms of 1. Applicants having to mount an argument for non- notification 2. Council planners having to do an assessment of notification, with the risk of judicial review hanging over their heads.

Respect your view on urban design, and have some sympathy for it. There’s something to be said for accepting ‘the good, the bad and the ugly’ of cities.

On notification, great idea - depending of course on what becomes discretionary in future. But, really agree with your point on the unproductive wastage in the current system - ridiculous. To my mind (and I'd like your opinion of this) at the moment something like less than 1% of a consents are publicly notified. Of course, I'd hope in future that there are just a lot, lot less consents (far more permitted activities). But more generally it does seem to me that that current stat is pretty right - very few activities/projects are of such a significant impact that they should be subject to wider public scrutiny. And I also wonder whether for some of the more controversial projects, such as the Waiheke Marina development or the Kāpiti Gateway - whether we would be better to introduce provisions for local citizen juries - as opposed to local hearings panels.

I should rephrase what I said. I am not so concerned about the nebulous concept of ‘urban design’ being missing. I am more concerned about amenity in terms of things such as access to daylight and sunlight. For most people these would be pretty central to wellbeing and liveability. And of course access to sunlight is important in terms of energy. This will be one of a number of things I submit on.

Japan is one of the things mentioned elsewhere here. I quite like some of their approaches, such as focussing on core things such as building height and sunlight access (ie. amenity) and not focussing at all in terms of design. I also like how the Japanese planning system enables very small scale commercial uses in residential neighbourhoods.

You both obviously haven't noticed that our urban areas are being built by group house builders, or developers who have their houses designed by CAD designers. The result is awful architecture and you cant have a quality “built environment” without good architecture! The uproar in Mt Wellington about houses that looked like “shipping containers” being but one example.

I like the concept of environmental limits. This should reduce the amount of time and resources wasted in attempting to come with a local authority setting arbitrary limits based on the resources of the applicants. Less chance of low level cronyism and corruption.

I agree on that aspect.

Me too.

...draws on te Oranga o te Taiao, a te ao Māori concept that speaks to the health of the natural environment

The Japanese also draw on their inherent cultural values regarding space, design and the natural environment. On the whole, I think they do a much better job at implementing these values into "harmonious" urban development and regulation. Is it perfect? No. Is it better than what appears to be happening in NZ (nothing), then yes.

It's also quite amusing to see how Māori concepts need to be filtered and translated through a bureaucracy mindset and prism.

Yes, I and many in my family have what I would call an intrinsic relationship with the environment - or put a better way, many people feel at one with nature in a spiritual way.

If they substituted "people and communities" for "iwi and hapū" I think many NZers would be able to identify with that environmental ethic - a move in the direction of something shared across cultures.

That said, I teach the philosophy of ethics, so I'm likely a whole lot more comfortable with the idea that environmental management (use, development and protection) has an ethical premise associated with it. Even utilitarian ethics recognises that inexorable link between humans and the environment - the emphasis being on use and development for anthropocetric purposes, but nonetheless it is an ethical view.

Why do you think the Japanese do it better?

Because the offshore their resource-use. Always have. Keep their own intact. Went to war over it, once.

Same reason the proposed - and the old - legislation fail the sustainability test here: we offshore damn near everything; mining, fossil-energy extraction, carbon offsetting, food/feed supplements.....

JMTCW. No expert at all on it - just a visitor/observer. I think they have a shared environmental and aesthetic ethic - more homogenous in terms of their society. Also (in my experience) a very 'agreeable', non-confrontation people. Not the same 'keeping up with the Jones' western mentality. A clearer respect for public good. Stronger sense of tradition (Māori would call it tikanga) - its shared and it matters.

(d) the intrinsic relationship between iwi and hapū and te Taiao

This fourth ‘limb’ (clause (d) above) looks to have been latently added to the definition, as it is not mentioned in either the Randerson Report, nor the Government’s explanatory note. I doubt it has been through the same rigour in consideration that other changes to the Act’s purpose have been.

A fair assumption over clause d Katharine.

And how do applications cover off the intrinsic relationship? Bottle neck in the making both time and cost in consulting with local iwi.

Good luck New Zealand, yet another mess brought about by incompetent Labour ministers.

Yes, serious potential bottle neck - see my comment above to re-word more in keeping with the inclusivity of the RMA Purpose which refers to people and communities.

We spent so much money and time trying to clarify the meaning/interpretation of RMA Section 5 (Purpose). And more recently of course the Supreme Court moved away from the 'overall broad judgement' approach/precedent that was set early on in RMA case law. We have got to get the Purpose tight and right this time around to avoid that kind of ridiculous waste of human (time) and financial (cost) resource.

Every new piece of legislation is now littered with reference to Maori, just like the nebulous “principles of the Treaty” which has found its way into the Spatial Planning Act. Completely undefined of course.

I am deeply suspicious the changes will result in greater enforcement. It will be the same Local Councils, many too close to those they “regulate” or more focused on “customer service” than meeting their responsibilities under the Act.

in my view enforcement should either be undertaken or audited by the EPA.

Eric Crampton's take on the New Gordian Knot is worth reading. Essentially, there are so many mutually incompatible Objectives, and no methods for weighting 'em in some sort of sensible hierarchy, that the New Bureaucracy will be able to find novel ways to stifle, well, almost anything. By pointing to an Objective that is ever so slightly Bruised by the proposal.

And the kicker, which Eric does not mention, is that activities undertaken without consent, quietly, on properties with high fences and paid-off neighbours, have, as per now, free rein.....

His article in Newsroom is worth reading;

What interests me is that the argument is basically one surrounding growth, and in particular the need for urban growth.

But is growth good, particularly urban growth? I'd suggest urban renewal is better than urban growth.

And he's got a good point about Auckland viewshafts. I don't live there but I do wonder how many Aucklanders would bemoan the loss of a viewshaft in terms of their 'sense of place', or feeling regarding the city's overall identity/amenity? Perhaps the long-term spatial plan will not provide for them anymore - and if that were the case - would there be some kind of major kickback from the public?

Thank you so much Kate for your thoughts....It is indeed a mammoth task! Our very chequered experience with the last attempt, the RMA is a cautionary tale indeed.

It was a bill introduced into Parliament with some haste, not even drafted or vetted by the usual Parliamentary agencies, & in fact was lost when the then Labour Government was voted out, but the incoming National Government (rather naively) enacted their predecessor's Bill in 1991. It was touted in very similar terms to this new proposal, promising to be faster, cheaper and better than the old Town & Country Planning Act. And we all know how it turned out, although the true cost of implementation has never been measured. I would hazard a guess of billions of largely wasted dollars which might have been much better spent on hospitals, transport, schools etc., & even specific environmental protections (eg pest control)

The moral of the story might be summed up as a comparatively poor nation with champagne tastes, or perhaps the old adage of "perfection is the enemy of good".

The problem is, that much of our modern, shoddy legislation starts with "nice", "inspirational" objectives, but whose precise legal meaning is very hard to define. It seems that those who draft the principle legislation aren't worried about any unintended consequences and really just expect the bureaucrats to produce detailed regulation in due course to fill in all the unknowns.

In my view it is useless to try to develop any body of law until the major, wider questions (of in this case) of land management have been widely discussed and as much consensus as is practical has been reached.

In particular, a discussion on the reasonable rights and responsibilities of land ownership, & secondly how our nation state is to preserve the rule of law and the best methods of democracy whilst respecting the reasonable expectations of a range of minority interests, eg tangata Whenua. Not easy or quick matters!

If the Act was only about land management - that would be much easier. But the RMA had the idea of integrated resource management at its core (it repealed I cant recall exactly how many other pieces of legislation when enacted - 30+ I think). This new reform follows that approach - rules for the management of soil, freshwater, coasts and air/atmosphere and the built environment. The NBA 'does' all that and in addition, seeks to manage/provide for infrastructure development, including transport.

In their submission on the exposure draft, my colleagues argued for two separate acts - one to manage the built environment and another for the natural environment - the latter, more often than not, relating to the use and development of common pool resources.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.