By David Skilling*

‘We all know what to do, we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it’, Jean-Claude Juncker.

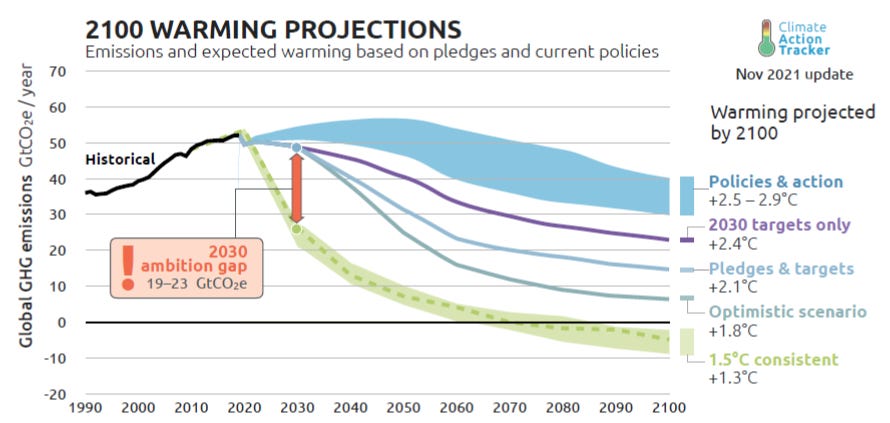

Progress was made at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow. Although the commitments made fall short of what is required, it was more than ‘blah, blah, blah’.

But addressing climate change is a deeply political process, and policy approaches need to respond to domestic political realities to make meaningful progress. In thinking about the best way forward, it is useful to learn from the good and the bad of managing globalisation.

First, avoid utopianism. The claims that free trade would inevitably create prosperity and that the distributive impacts would be taken care of by rising incomes (and assumed compensating policies) led to policy neglect. Now similar claims are made that aggressive climate change policy will simultaneously deliver net zero as well as green jobs and prosperity. From the US to the EU and beyond, the green transition is portrayed as central to strong and inclusive growth.

I’m in favour of both trade liberalisation and net zero, but the associated costs and risks need to be recognised and managed. A utopian view that sees everything as win-win is likely to lead to political pressures that undercut the feasibility and sustainability of effective policy. And there is no time for delay in reducing emissions.

International economic integration has led to a backlash in some countries. For example, the ‘China shock’ on US manufacturing, and the politics around migration in the UK, contributed to the election of Mr Trump and the Brexit vote respectively – both of which led to reversals in integration.

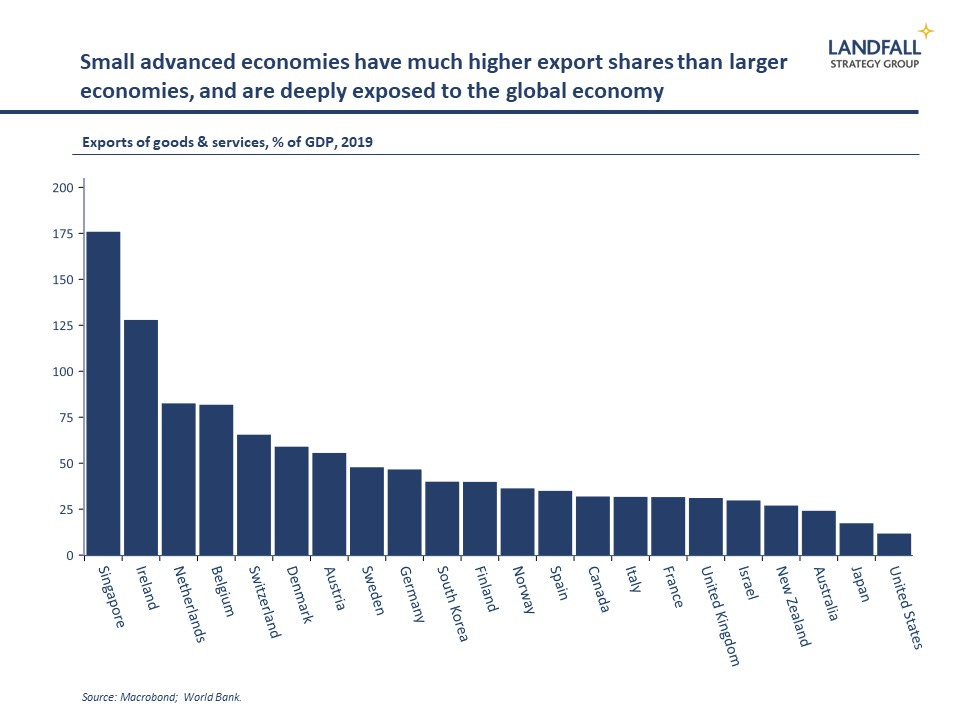

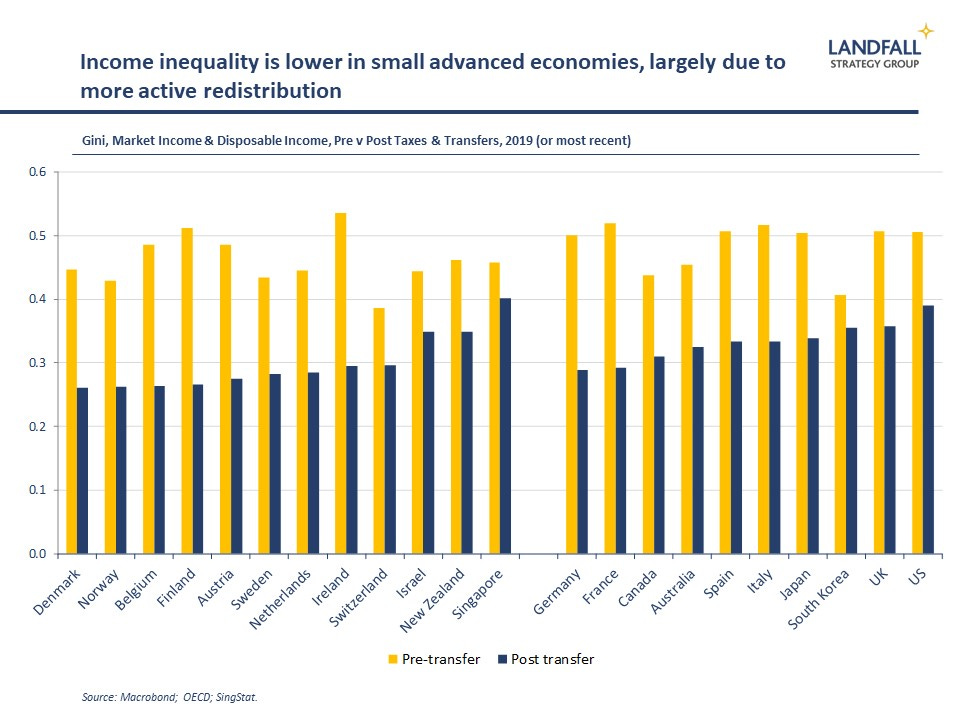

Second, deliberate policy responses can capture the opportunities and manage the risks. It is striking that political pushback on globalisation has been stronger in the US and the UK than in small open economies that have managed their deep exposures to the global economy.

Small advanced economies have focused on managing risks and ensuring that the costs and benefits of global engagement are broadly distributed; through social insurance, active labour market policy, and so on. And they have actively worked to develop competitive advantage in global markets. This policy approach has allowed small economies to maintain high levels of support for open policies.

From globalisation to climate change

This experience is relevant to designing climate change policy. As with globalisation, the net zero transition offers the potential for substantial economic benefits: new jobs in the green energy sector, new low emissions growth sectors, and cheaper energy sources over time (as well as avoiding the economic costs of environmental disaster).

Indeed, some emissions reducing activities come at negative cost with existing technology - and some companies already see a market for low emissions goods and services.

But there are also significant economy-wide transition costs: emissions intensive goods and services will become more expensive (energy and transport); the value of substantial amounts of capital will be destroyed; and there will be disruption to labour markets. It is a significant negative supply side shock. And people on lower incomes will often be disproportionately exposed to these costs.

Public concerns about risks to household incomes are slowing policy change: note the protests in response to rising energy prices or proposed carbon taxes, from France to New Zealand. The climate-conscious Biden Administration has responded to high energy prices by exhorting OPEC to increase supply.

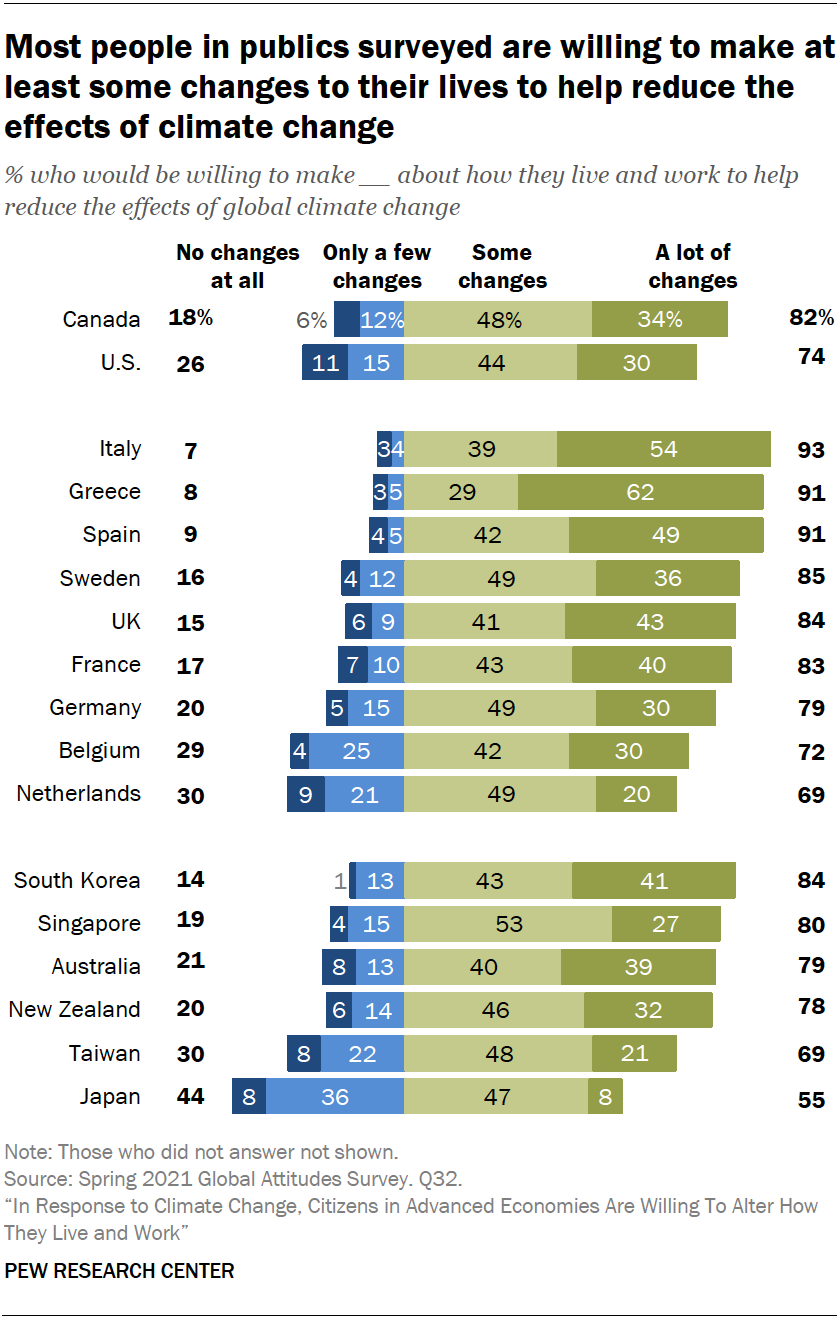

Although surveys report widespread public concern about climate change and support for policy action, there are limits to the public’s current appetite for substantial change.

These political realities explain why aspirational statements of political intent and net zero targets are running well ahead of policy action. In politics, losses are weighted more heavily than gains.

The international politics of climate change also complicate the transition. The costs and benefits are unequally distributed around the world. Whereas many developing countries pushed trade liberalisation, many fear the economic and financial costs associated with a rapid transition to net zero. The financial support required to create political space in developing countries has not yet been forthcoming.

So what to do?

The insight from small economies that have managed globalisation best is that getting the domestic politics right is the precursor for meaningful progress. Climate change policy needs to be oriented around widely-shared welfare.

Without a well-developed, ambitious policy strategy to maximise opportunities and manage the costs and risks of the green transition, there will not be broad-based political support for ambitious climate change action – and there will be a likelihood of policy reversals.

This matters because a major economic transformation is required in a compressed time frame. The IPCC estimate that emissions will need to be halved by 2030 to hit the 1.5 degree target, on the way to net zero emissions by 2050. Updates prepared for the COP26 meetings show that there is a long way to go.

Actions to create the political space for this transformation include active labour market policy to provide displaced workers with skills and opportunities to move to new jobs; adapting national economic strategies to support opportunities in the low emissions economy, and reducing reliance on high emissions strengths; and providing compensation to those exposed to higher prices, such as through recycling carbon tax revenues.

Government balance sheets should also be used to support the transition – investing in renewable energy, supporting the development of new low emissions industrial and transport systems, and so on. This investment can help push the supply side out, encouraging the development of new technologies as well as supporting a fairer transition. The policy response has to be broader than simply implementing carbon pricing.

A rapid transition is more likely to be politically feasible if households and firms can see attractive alternatives, from compelling jobs and high quality public transport to competitive energy alternatives. At the moment, some low emissions policies (e.g. subsidising electric cars) are seen as supporting the preferences of the wealthy at the expense of the lower income.

Although international action on climate change is important and necessary, the binding constraint on progress is what national governments are politically prepared and able to do. Climate change politics remain largely local, and aggressive domestic policy innovation is needed to respond to these realities.

To subscribe to David Skilling's email newsletter, use this:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. This article first ran here and is used with permission. Skilling recently spoke to interest.co.nz in a Zoom interview.

30 Comments

I find it amusing that the countries with the highest percentage of people willing lots of changes to reduce the effects of global climate change are also the most broke.

That brings up another chicken and egg question; are green ideologies causing them to be broke or did they subscribe to the green fad after they went broke?

I think it's the expectation and incentives of free green money in the form of generous subsidies that are driving ordinary folks from broke countries to subscribe to the green fad.

Wrong on all counts.

The problem is that none of them - green, red, yellow, blue - understand what underwrites money.

His "I’m in favour of both trade liberalisation and net zero" tells us he doesn't get it either.

In an essay I wrote recently, The Path to a Green Economy with a focus on the importance of a declining EROI, I said this; " I think it unlikely that the desire to maintain our lifestyle will be easily surrendered. I may of course be wrong, but I think that when threatened, he first instinct of many will be to protect their existing way of life."

An NZ journalist made a similar point very recently; " Asking people to pay more taxes and higher costs to combat global warming, while asking them to accept living standards stagnating or falling is unrealistic".

Politicians are trying to tell us that we can just carry on with our current lifestyle while the transition to a decarbonised economy takes place seamlessly behind the scenes and that's a big lie. Much of the apparent support for measures to tackle global warming is, i think, very soft and will rapidly fall away when these measures threaten their lifestyles.

Real change in attitudes will have to wait until the the problems become too big to ignore.

"Real change in attitudes will have to wait until the the problems become too big to ignore." That could be translated into saying we are completely stuffed, because by the time the problem is too big to ignore, momentum in planetary heating will be such that collapse of civilisation is virtually assured!

Basically the human race will continue to drive at 100mph regardless of any speed limits you try and put in place. It will all only stop when we hit a brick wall created by nature. Politicians will have to try and enforce change and we all know how popular that will be so they will not get re-elected. Its doomed to fail and COP26 was a waste of time as we all know we are just kicking the can down the road.

What is there more to say Carlos except, Yep.

Well, one could always not worry about what everyone else is doing, and make your own changes. Plant a few trees, reduce your energy use etc. You"LL find your not alone, and you might find it satisfying.

Did all that, a generation ago. Showed how to live, low energy, low impact.

Nobody listened, nobody copied.

So now I address what will happen when TSHTF. Which it will.

Good luck with that optimism bias :)

You have mini-hydro - and not everyone has a stream on their property in order to get that self-sufficient - same goes for much of the food you raise; perhaps a bit harder on a 600m2 section?

Not saying what you have achieved isn't remarkable, it certainly is, but some of it comes down to the amount of land you have.

Like a lot of commentators on this subject, this author offers nothing but the same platitudes we get from government.

We need people to suggest practical transformational policies that will drive the necessary changes in order to avoid the point you make that;

Real change in attitudes will have to wait until the the problems become too big to ignore.

So here's mine for reducing transport emissions.

Announce that in one year, all residential roadside parking spaces will be abolished. The space/lanes afforded by the move will be shared-use by commercially registered ride share operators (e.g., Uber), cyclists (if there is no existing cycle lane) and electric golf carts. At the same time - all public transport will be made free-of-charge.

People in residential areas who park on the streets, will either have to downsize the number of vehicles in the household and/or clean out their garages and/or park on their own lawns/sections.

No ones property rights are infringed; the land is all public property. No one is forced to buy anything or pay anymore for anything. Free public transport will help the disadvantage and those with children who bus to school significantly. Far less private vehicles will be needed in the longer term and the commercial ride share sector (self-employment opportunities) could grow significantly.

Nobody wants that though. I feel like people want some magic stuff that does all the changes without them having to do anything, 78% of the population are willing to make that kind of change.

When the climate change story first broke, ten or twenty years ago, the Listener published a cartoon by Tom Scott, depicting a Chicken Licken character with the sky falling on his head and the caption " Quick, somebody else do something"

Agree about us doing something practical ourselves. And it seems any government change cashflow will be to government trougher organisations and corporates. None to folk.

But also the car is the best and greatest personal transportation device. So what to do personally

1. Two Ev vehicles. We keep cars for more than a decade. But EVs will happen.

2. Solar. I have seen the claim that a domestic system is the equivalent of one and a half hectares of trees. Good reason to whack those up. Subsidy?

3. Seems my house solar produces enough spark to run three average cars. So why be a bureaucrat dick to car owners if we each had a solar on the roof.

4. Given petrol cost now, using your solar for your car seems to have massively short payback time. Why not. Might run another bank of panels.

Overall I see our future as an electrified country, with massive distributed generation. And that will mean taking the control from the big corps. (including the government ones)

I did read PM Adern's carbon piece in stuff today. Clueless, nothing organisational, or practical.

Practical is what we need.

No need to subsidize residential tie-back solar - all the Government need to do is allocate residential solar end-users carbon credits (which they can then sell or retain as an asset).

They do this for farmers (i.e., they get 100% of their emissions subsidized - i.e., free-of-charge) and energy intensive industries are subsidized too (they get either 90% of the credits they need allocated to them for free; or 60% depending on the size of the industry);

For example; highly emissions intensive firms face NZ ETS costs of 10% of their emissions, and moderately emissions intensive firms face 40% of NZ ETS costs.

By reducing their emissions they may be able to benefit from selling NZUs allocated to them. The allocation of NZUs is calculated on production levels, so if a business reduces its emissions while maintaining production levels it will have extra NZUs which it can sell.

The only entities in New Zealand who the Government doesn't give a free-pass to are the general public/residential users of energy.

Someone needs to pull them up on this.

Kate,

And just what would be the re-election prospects of the government if they proposed these measures? I would suggest that the answer is nil, or even less.

Normally your comments are thoughtful, but this is absurd. We don't have the public transport to accommodate the millions who would be affected, but practical issues aside, there would be mass insurrection.

A bizarre article ..

The author argues for being realistic and not glossing over the problems "green" policies would create however he blithely glosses over the largest and most obvious problem with the whole process - namely that there is no way most the worlds largest polluters ( China , India , Indonesia , Russia , Brasil .. the list goes on ) would deliver on any promises even if they make them.

An effective global agreement on greenhouse emissions - one is that is actually adhered to - is a pipe dream . Love it or hate it mitigation is the only way forward.

unless the top 2 polluters pull their heads in it's a waste of time for the rest to even try. China and the USA account for 75% of the problem.

The human race is largely self centred, it was probably a survival strategy, but if the price of energy increases we will use less energy. I noted, for example, US drivers are predicted to drive less miles for thanksgiving because of petrol price increases, though I wonder if COVID may be a factor.

The politicians can wait an let pricing do the unacceptable work, and not take the blame.

I'm quite happy to have a 2.5-2.9C increase in temperature. Wouldn't bother me at all. It would be less change than moving from southland to northland.

Seems like the majority of the population is willing to make changes, my question is what is stopping them?

You're confused. Climate change is about a lot more than a change in temperature - it's about unpredictable and extreme weather patterns, crop failure, huge change in where is warm (and cold), sustained migration of millions of displaced peoples etc. Little NZ will not be isolated from the chaos that is coming.

WJ - then you don't understand the physics.

At all.

Why is is that so many folk hear what they want to hear? What do you think the red sky was from Australia, when they were all crowded onto the beaches? Do you think BC won't have another '1-in-500-year flood within a decade? That's AVERAGE temperatures, but temperature is energy-delivered. That means weather-events of unprecedented intensity - because there's unprecedented energy going into them.

Spare me - we need to be a helluva lot more sapient, a helluva quickly

Whiskeyjack,

Given the spelling, I assume it's Irish Whiskey. I also assume that you have your tongue firmly in your cheek.

The hard reality that so many commentators (and Governments) are finding it hard to swallow is that Government is going to have to get bigger, do more directly, and mobilise significant resources to transition to economies that are not powered by fuels and systems that dump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

The winners at the end of the 21st century will be the countries that have managed this transition the best. They will typically be countries that put together a clear 10 - 20 year plan and sold it well to the public - offering, as the author writes, an attractive vision of a better future. - where kids can swim in rivers, houses are warm and dry, the bills are cheap, cities are amazing places to live, involuntary unemployment is a thing of the past etc. The countries best placed to do this will have fertile soils, clean water, wind, solar, hydro, skilled people to work in low carbon sectors, and relatively high trust in Govts (sound familiar?)

The countries that lose out will not have the natural resources to sustain themselves and / or they will have placed their trust in 'the market' to set their forward path. These countries will be strewn with stranded assets and will be paying a fortune for things that they can't make themselves (solar panels, building materials) whilst trying to sell things (oil, beef, etc) that other countries don't want (or can't afford due to vicious tariffs).

At the moment our path looks a lot more like that of a loser.

Nicely put . For many climate change policies are merely a conveniently disguised vehicle for a broader socialist agenda.

Actually, egalitarian is the only way we can survive. Dog eat dog is why we're in the current poo.

PDK,

It is not like you to suggest there is any dogma that could save society and I agree.

The Financial system will do the heavy lifting, passing increased costs on to any that cannot avoid them,

Governments will make largely ineffective changes to our economic systems, production and consumption.

All the workers can do is think carefully about transport and try to minimise their costs but it’s not really their problem.

I would be interested in your list of emergencies that the financial system has 'done the heavy lifting' to get us out of?!?

In fact I can only think of emergencies that have been caused by the financial system!!

A recent one would be the Marshall plan after the Second World War.

COP 26 was about the end of coal and the finances required to replace coal with renewables.

Personal efforts didn’t get a mention and that should tell us society doesn’t value that at present.

Calls for personal sacrifice are just a smoke screen for business as usual, and we should call that out.

The Marshall Plan involved the US Treasury printing millions of dollars to lend to European countries - basically to secure control over the western world?!? A modern day equivalent would be the Chinese banks printing $150 billion to finance the take over of mining operations in the Democratic Republic of Congo (thus securing the best supplies of minerals for battery production). I am not sure that counts as the financial system doing the heavy lifting - both involve state intervention on a massive scale.

100% agree on the personal responsibility thing - complete smokescreen!

They were on the gold standard in those days and most of it was pledged to war debts.

But that is neither here nor there, they kickstarted the European economy.

Im indifferent to the financial sector but it is the way the world has worked for centuries.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.