By John Mauldin*

Regular readers may have noticed me slowly losing confidence in the economy. Your impression is correct and there’s a good reason for it, as I will explain today. The facts have changed so my conclusions are changing, too.

I still think the economy is okay for now. I still see recession odds rising considerably in 2020. Maybe it will get pushed back another year or two, but at some point this growth phase will end, either in recession or an extended flat period (even flatter than the last decade, which says a lot). And I still think we are headed toward a global credit crisis I’ve dubbed The Great Reset.

What’s evolved is my judgment on the coming slowdown’s severity and duration. I think the rest of the world will enter a period something like Japan endured following 1990, and is still grappling with today. It won’t be the end of the world; Japan is still there, but the little growth it’s had was due mainly to exports. That won’t work when every major economy is in the same position.

Describing this decline as “Japanification” may be unfair to Japan but it’s the best paradigm we have. The good news is it will spread slowly. The bad news is it will end slowly, too.

Losing Decades

Before I explain why we will follow Japan, I want to briefly explain how Japan got to where it is. It was a long, slow process that, like the proverbial frog in boiling water, wasn’t fully obvious in real time.

Japan experienced rapid growth following World War II as the US and others helped rebuild its economy. That wasn’t all out of generosity; the country was geopolitically important as a Western bulwark against Russia and China. We didn’t want it to fall under the other side’s influence.

This eventually led to a roaring expansion that culminated in the 1980s Japanese asset bubble, which popped in the early 1990s. There followed what came to be called the “Lost Decade.” It was really more than a decade, as the early 2000s brought only mild recovery. GDP shrank, wages fell, and asset prices dropped or went sideways at best.

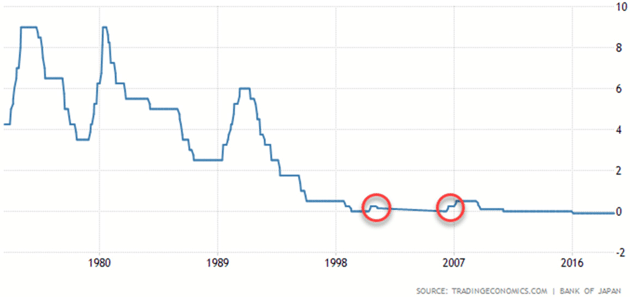

The Lost Decade had monetary roots, namely the 1985 Plaza Accord that drove the yen higher and inflated the asset bubble. The Bank of Japan tried to pop the bubble with a series of rate hikes beginning in 1989. This chart shows the BOJ’s benchmark rate.

Source: TradingEconomics.com

Upon reaching 6% in 1992, the BOJ began cutting rates and eventually reached zero a few years later. Since then it has made two short-lived tightening attempts, shown in the red circles. Neither worked and that was it; no more rate hikes, period.

The BOJ has now kept its policy rate at or near zero for 20 years, making conventional monetary policy essentially irrelevant. The BOJ resorted to increasingly large QE-like programs that also had little effect.

Meanwhile, the government tried assorted fiscal policies: infrastructure projects, deregulation, tax cuts, etc. They had little effect, too. GDP growth has been stuck near zero, plus or minus a couple of points. So has inflation.

The only thing that really helped was driving down the yen’s exchange rate, which successive governments and central bank governors have done enthusiastically. Which I kind of understand… when your only tool is a hammer, you treat everything as a nail.

That said, the BOJ’s asset purchases certainly had an effect. They more or less bought everything that isn’t nailed down, including stock ETFs and other private assets. Japan is a prime example of the faux capitalism I described last week. All this capital is going into businesses not because they have innovative, profit-generating ideas but simply because they exist. That’s how you get zombie companies.

The result, at least so far, has been neither boom nor depression. Japan has its problems but people aren’t standing in soup lines. The bigger issue is that the population is aging rapidly. Many say the present situation can’t go on indefinitely but there’s no exit in sight. The Bank of Japan has bought every bond it can except those the government will create to fund future deficits, which is why they are buying stocks not just in Japan but in the US as well. They are trying to put yen into the system in an effort to generate inflation. It simply hasn’t worked.

When you don’t have a better answer, the default is to do more of the same. That’s the case in Japan, Europe, and soon the US. Charles Hugh Smith described it pretty well recently.

The other dynamic of zombification/Japanification is: past success shackles the power elites to a failed model. The greater the past glory, the stronger its hold on the national identity and the power elites.

And so the power elites do more of what's failed in increasingly extreme doses. If lowering interest rates sparked secular growth, then the power elites will lower interest rates to zero. When that fails to move the needle, they lower rates below zero, i.e. negative interest rates.

When this too fails to move the needle, they rig statistics to make it appear that all is well. In the immortal words of Mr. Junker, when it becomes serious you have to lie, and it's now serious all the time.

“Do more of what’s failed in increasingly extreme doses” is also a good description of Federal Reserve policy from 2008 through 2016. Zero rates having had little effect, the Fed launched QE and continued it despite the limited success and harmful side effects. The European Central Bank did the same, in even larger amounts than the Federal Reserve also with little effect.

Which brings us to the next point: why Europe and the US will follow Japan.

Too Much, Too Fast

As noted in the introduction, I change when the facts change, and in the last few months they did.

The Federal Reserve spent 2017 and 2018 trying to exit from its various extraordinary stimulus policies. It began raising short-term interest rates and reversing the QE program. I think it should have done both sooner, and not at the same time, but both needed to happen.

In hindsight, it now appears the Fed tried to do too much, too fast. Which was my point when they started the process. Either raise rates slowly or reduce the balance sheet, but not both at the same time. Reducing the balance sheet has an effect on effective rates just as actually raising rates does, but not as obvious. My friend Samuel Rines calculated that when you include the QE tapering, this Fed tightening cycle was the most aggressive since Paul Volcker’s draconian rate hikes in the early 1980s. They should have started sooner and tightened more gradually. For whatever reason, they didn’t.

And so the complaints began. Wall Street wasn’t happy but, more important, President Trump wasn’t pleased with the rate hikes. Why it surprised him, I don’t know. Jerome Powell’s hawkish bent was no secret when Trump made him Fed chair. Whatever the reason, the president has made his displeasure with Fed policy clear.

But the real deal-breaker may have been the late 2018 market tantrum. Lenders and borrowers alike grew increasingly and vocally distressed as the yield curve flattened and threatened to invert. Then this year it did invert at several points along the curve, coincident with weakening economic data. That was probably the last straw. The Fed hasn’t exactly loosened, but there’s a good chance it will later this year.

Meanwhile, across the pond, Mario Draghi had one foot out the door and until a short while ago had a tightening plan in place. That plan is now out the door before Draghi is even close to gone. So on both sides of the Atlantic, plans to exit from extraordinarily loose money now look disturbingly like those two little circles in the BOJ rate chart when it tried to hike and found it could not.

Worse, we are also replicating Japan’s fiscal policy with rapidly growing deficit spending. In fact, this year we will be exceeding it. The Japanese deficit as a percentage of GDP is projected to be below 4% while the US is closer to 5%. And given the ever-widening unfunded liabilities gap, the US deficit will grow even larger in the future.

Turning Japanese, I think we’re turning Japanese, I really think so. (With a musical nod to The Vapors.)

A $6 trillion $10 Trillion Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

Let me give you the Cliffs Notes version of how I think the next decade will play out, more or less, kinda sorta.

We already see the major developed economies beginning to slow and likely enter a global recession before the end of the year. That will drag the US into a recession soon after, unless the Federal Reserve quickly loosens policy enough to prolong the current growth cycle.

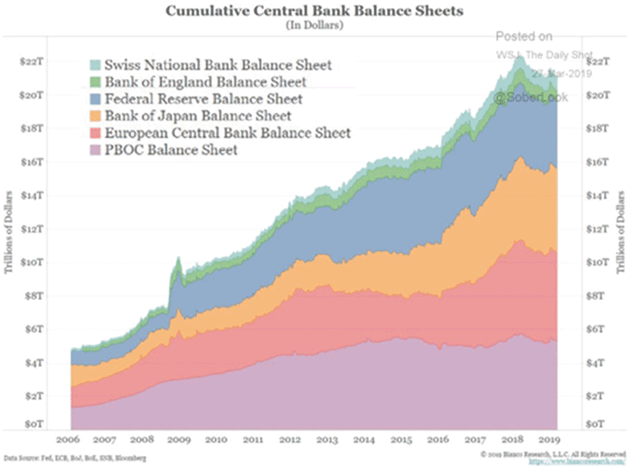

Other central banks will respond with lower rates and ever-larger rounds of quantitative easing. Let’s look again at a chart (courtesy of my friend Jim Bianco) that I showed three weeks ago, showing roughly $20 trillion of cumulative central bank balance sheets as of today. If I had told you back in 2006 this would happen by 2019 you would have first questioned my sanity, and then said “no way.” And even if it did happen, you would expect the economic world would be coming to an end. Well, it happened and the world is still here.

Source: Jim Bianco

Before 2008, no one expected zero rates in the US, negative rates for $11 trillion worth of government bonds globally, negative rates out of the ECB and the Swiss National Bank, etc. Things like TARP, QE, and ZIRP were nowhere on the radar just months before they happened. Numerous times, markets closed on Friday only to open in a whole new world on Monday.

In the next crisis, central banks and governments, in an effort to be seen to be doing something, will again resort to heretofore unprecedented balance sheet expansions. And it will have less effect than they want. Those reserves will simply pile up on the balance sheets of commercial banks which will put them right back into reserves at their respective central banks.

During the worldwide recession, there will be few qualified borrowers but a great demand for liquidity as corporate debt goes from investment grade to junk seemingly en masse. Which will disqualify them from being bought by pensions, insurance companies, and many other purchasers normally looking for yield.

The inverted yield curve is a classic sign that the central bank, in this case the Federal Reserve, has tightened monetary conditions too much. Which is why Trump wants the Fed to lower rates now (plus he doesn’t want a recession in an election year) and Powell and the Fed turned so dovish.

I will admit the Fed’s $4 trillion balance sheet expansion surprised me at the time. Fool me once, shame on you. We’ve now seen the new playbook. At a minimum, they will keep the balance sheet at its present, barely-diminished size and eventually add a lot more when we go into recession. I think $10 trillion is almost a sure thing by the mid-2020s, by which point we will have been through our second recession.

Why? Because we will see a new government at some point that raises taxes enough to actually send a still-weak economy into another recession. That’s pure speculation on my part but is what I foresee.

What assets will the Fed buy? Under current law, that’s pretty predictable: Treasury securities and a few other government-backed issues like certain mortgage bonds. That’s all the law allows. But laws can change and I think there is a real chance they will—regardless of which party holds the White House and Congress. In a crisis, people act in previously unthinkable ways. Think 2008–2009.

They will think the unthinkable in the next crisis and try everything, including the kitchen sink, but it will just increase government debt. And as Lacy Hunt has shown us from numerous sources in the academic literature, and I’ve tried to explain, that debt will be a drag on future growth.

Another reason to expect a $10-trillion Federal Reserve balance sheet is that US government debt will be north of $30 trillion. On top of that, in the next five years the credit markets have to fund $5 trillion of corporate debt rollovers, plus new debt, plus state and local debt. It won’t be coming from outside the US and there is only so much that banks and big pension funds and individuals can do. Unless the Federal Reserve steps in, interest rates will soar and the crisis will become much worse. It will have little choice but to step in and buy US government debt.

Yes, I know this is a self-fulfilling prophecy, and it has to end. But the question is when? We’re already seeing serious analysts say it really doesn’t have to end. This from none other than Goldman Sachs.

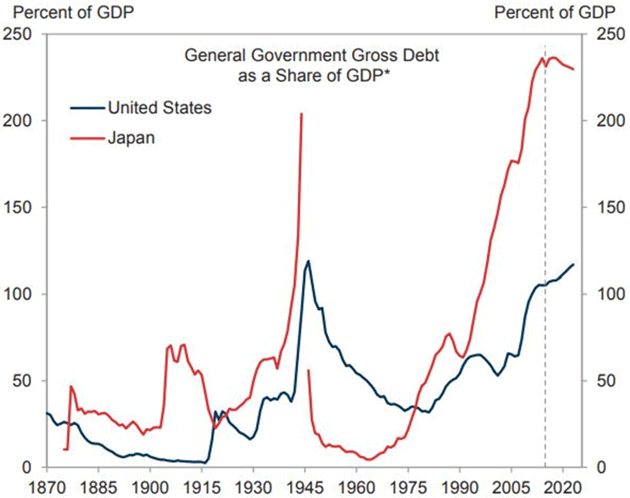

Daan Struyven and David Mericle, economists at Goldman Sachs, said the example of Japan could prove instructive as the world’s third-largest economy had not suffered a debt crisis, even though it arguably has the most public debt as a share of its GDP in the world. Japan’s government debt-to-GDP ratio sits at 236% in 2017, more than double that of the US, which stands at 108%, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Source: MarketWatch

I could spend the entire letter giving you quotes like that from mainstream economists. Note you can quibble with the exact numbers but in any case, the Bank of Japan holds at least 100% of Japanese GDP in debt, plus an enormous amount of Japanese stocks, not to mention global stocks.

The Federal Reserve holds roughly 35% (give or take) of US government debt. Can we even imagine the Federal Reserve at some point holding $20 trillion of US government debt? I don’t think the Japanese imagined that 20 years ago.

I keep saying we have to think the unthinkable as we plan for our futures because I can guarantee you that future leaders will. When there is a true crisis “they” (whoever they may be) will be looking for action and “do nothing” will not be an option. Maybe it should be, but that is a metaphysical argument for another day. They will do something. Quantitative easing is now on the table and I think will be almost a reflexive move during the next recession\crisis.

So, will we have Japan-like flat markets and low growth for years on end? Will we create a demographic crisis by limiting immigration? Public pensions and insurers are already struggling to meet obligations after years of low rates. Those betting on 7% returns (and many are) won’t make anything close to that. This will make government debt and state/local pension fund obligations a massive problem that the Federal Reserve and the US government right now are not politically or legally capable of handling. Will we change the rules in the future? Tell me who’s going to be in charge during that crisis… and then let’s ask the question.

But will it play out over a longer period of time than we might think now? Almost surely. Yet the world will not end and, for those paying attention, will be a better world. Stay tuned and stay with me.

*This is an article from Mauldin Economics' Thoughts from the Frontline, John Mauldin's free weekly investment and economic newsletter. This article first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

42 Comments

Nice piece, I agree with most of it.

Of course, it is about Europe and the USA.

Assuming NZ and Aus keep importing people at reasonably high rates, we won't have the same population stagnation / decline issues that Japan has had.

But the big picture factors still apply.

"Of course, it is about Europe and the USA."

Almost certainly not USA .. the demography there is just to different from Japan . Even Europe has more capacity to import people than Japan would / could ever tolerate politically .

Possibly a big difference between Japan and the rest of the Western world is the high immigration levels. Quite a lot of activity must be generated just by having to look after so many different diverse people that it is a type of new industry in itself.

The Herald had an article about how different ethnic groups are poorly represented in official NZ data etc. We need to identify every different group and ensure we cater for their needs which will generate huge opportunities in health and education and who knows what else for workers. As we move away from 19th century style production to the well being of all individuals we will really need to pour a lot of time and effort into this project. I'm not really joking about this either.

Actually migration to Japan from Vietnam and the Phillippines is increasing at a rapid pace partly to fill gaps in healthcare for an ageing population (as well as in manufacturing, agriculture, and service industries). Furthermore, the Japanese education system is growing because of the influx of foreign students. Japanese language is far more popular and ubiquitous for study than Mandarin in Vietnam.

Migration to Japan may be growing at a rapid pace but that is because, by Western standards, it is at a very low level. In 2015 there were 2.223M foreign residents, in 2017 2.471M. 2.5M was touted as a record high for Japan in 2018. Growing rapidly? Really? This is slightly less than 2%. Compare that to NZ or even the US. Imagine if two out of a hundred people were foreign born at your place of work. I looked around at work today and there were no NZ born people in the office.

OK. In the case of NZ and Australia. GDP per capita is deteriorating. In Japan, it is not.

So who's better off and what rate of migration is better?

Exactly. Japan is dealing well with a steady state economy , sustaining demand via fiscal policy despite demographic shifts. From Maudlin's description you'd think Japan was some dreary dull sort of stagnating place. Not my experience of it. Japanese businesses seem to have a wonderful respect for not only profit, but for customer satisfaction and social contribution. And as a consumer, Japan does not disappoint. Never seen such quality choice at low prices. A Japanese 100 Yen shop puts the Warehouse to shame. Public infrastructure is also amazing. The aging population seems to me to mean a lot of wisdom pervades policy choices. Lots to learn from Japan.

I read that article and Spoonley has a point - what is 'Asian'? Does say a Korean walking down the street seeing a Sri Lankan coming the other way say 'wow there is another Asian'. He is right for his statisitical work but when he claims unrecorded ethnic groups feeling 'marginalised and unrecognised' he is speaking rubbish.

My wife is a Mekeo from PNG and there may be two or three living in New Zealand - from her perspective everyone else is just unlucky not to be like her. My grandson is a combination that is probably unique in the world with a mix of a specific Papuan (Mekeo), Low Island and Western Highlands (all melanesian but ethnic cultures separated for over 60,000 years).

The significant fact about all ethnic groups in New Zealand is that they all want to be here. Listening to the sad stories about the victims in Christchurch a common theme was how they were involved in NZ society; they came from many countries, their faith was Muslim but their jobs and their sporting clubs and their interests were Kiwi.

Finally a good article that highlights the structural nature of global growth. Good job.

A quote that basically captures the nature of the structural problem globally, and increasingly so within Asia.. "For the first time in recorded history, there are more people aged over 65, than there are under 5"

Another good read for anyone interested

https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/asia/article/2180421/worse…

Yip , its called deflation, and I have been going on about it for years .

Very interesting piece John will have to read it more closely later.

Socially we nzers are very different to Japanese which could play a part and also multicultural.

Houseworks, "the world will not end and, for those paying attention, will be a better world" These are certainly wise words. Why bet your retirement on the one rental when asset prices will sink and debt owed will rise in size by ratio? In the near future, the buying power of those who are cash rich/debt free will increase considerably.

Something you may find very interesting Retired-pops: The top NZ summer bach destination goes to ... Hamilton? | Stuff.co.nz

https://www.stuff.co.nz/travel/111833707/and-the-top-nz-summer-bach-des…

And who do you think was booking those short stays...our brothers from the north heheh

Houseworks, if there's anything in this you can be sure the Hamilton Council will want to levy the ratepayers who use Airbnb and Bookabach. Hamilton's debt is eye watering. They are obsessed with rooting out additional revenue streams. It's a bit like choking the rooster before dawn.

Is that your best response?

Houseworks, the truth is ALWAYS the best response! You should know that by now.... :-)

Another good article, explaining the reality of the debt upon debt economic world we live in these days. It all works okay until someone can't pay their bills. It'll happen somewhere at some time. The trick, I think, is to not be the person holding the can at the wrong moment. But even then.....

When you think about the huge quantity of 'money' out there in circulation, you'd think there'd be enough everyone. The reality is it's all debt (bank credit) created & someone will have to pay the piper eventually.

Interesting article. To me the crux of this view is that companies are becoming increasingly profligate with resources (capital, human etc.) rather than genuinely focusing on reducing waste and promoting innovation. How do we increase management acuity in private companies towards tackle wasteful or inefficient practices? Also, seperately, your view seems to be a juxtaposition with those talking about a future where automation and robots makes companies more efficient?

Checking wikipedia and gross domestic product (at purchasing power parity) per capita has the Japanese about 10% better off than the Kiwi - the IMF, WB and CIA all agree. I would like my income to increase by a tenth.

For exports Japan is 4th and NZ is 52nd but they are much bigger. More significant is annual growth rate per capita - Japan's 1.9% is over double New Zealand's.

What are they doing right that we are doing wrong?

Working?

I think that is their problem - they haven't realised that the whole idea of becoming rich is to work less. A lot of Japanese work long hours, often unproductive sitting at their desk waiting for their boss to go home. They get very few holidays.

I wouldn't do that to be a tenth better off!

According to https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm Kiwis work 34 hours per year more than the Japanese. I still wish I was Japanese - less work and more money

Not according to the people I met over there.

They were amazed we get 4 weeks leave.

Most worked weekends and confirmed the 'don't leave before your boss' mentality.

Evening rush hour seems to be about 8 PM.

I highly doubt they work less than the OECD average, something fishy there...

Data versus anecdote. Which to believe... hmmm...

What are they doing right that we are doing wrong?

Productivity. Also, Maudlin fails to mention that Japan is a net creditor to the world partly because of their industrial output.

Ummm, the answer is pretty simple. They are using central bank funded fiscal deficits to offset private sector savings drains and sustain effective demand at near full employment levels and not worrying about public debt to gdp ratios cause the Yen is a fiat currency that is in unlimited supply. Basically they are MMT in action. Meanwhile in NZ the government hoards its surplus with its love of austerity settings to the detriment of us all.

I realise the situation is quite complicated, but since infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible, it's a bit odd that Japan's situation is considered to be 'bad'.

Is there actually a limit to economic growth on a finite planet?

Of course there is. What is the point of "economic growth" unless you can spend it on resources, and there's the rub.

When it is all boiled down, growth means more people, and we have to stop overrunning the planet.

Economic growth doesn't necessarily require more people. For example machines can create economic growth.

And not all resources are finite. Its quite conceivable that all of our food and energy needs could be met sustainably.

Oh boy, where to start. Machines creating economic growth, okay, but how does that happen? By people purchasing what they produce, so if population is decreasing then not so much stuff will be needed by a) fewer people b) older people, and if stuff is made by machines, then what are the people to purchase that with. Then, who owns the machines, do you have a handful of people with ownership so that any growth goes just to them or do you have ownership by the collective so all gain an advantage from it?

And yes there are resources that are not finite in terms of being able to do them over and over in the same place, but there is still a limit in terms of expanding them.

We truly, truly have to get over the idea that growth is finite, do you really want to come to that realization after we've wiped out the world's wildlife catering for our crazy notion that neverending growth is possible on a finite planet. It isn't and that is all there is to it.

Japan has a declining population and some farm land in the north is returning to wilderness. Compare to Auckland planning for an increase in population of 25% (0.5m) in the next ten years. Incidentally all previous Auckland plans seem to have under-estimated population growth.

I think what he says is feasible. I would add though that Japan exported its problems to the rest of the world by lowering its interest rates. With the rest of the world facing the same problem, who are they going to export it to?

So what's the go to investment in the coming economic environment?

There isn't one. That's the whole point.

The temporary game where money could apparently beget money, is no longer underwritten by the planet.

Yourself - not kidding

To move ahead it does seem like you need to expand in some way. China's recent successful expansion has happened because it had a huge pool of rural people that migrated and are continuing to migrate to the cities where the industrial centres are. In the past all great empires expanded as well as moved people from the countryside to the cities or to colonies.

New Zealand does have room to expand and by importing people it is kind of building up a mini empire. Of course it wont be without consequences. Already the change is dramatic which means the political and cultural character of our country has forever changed. People will need to give up on the idea of seeing their cultural identity reflected in their government. The government will become identity neutral.

Most modern citizens will become identity neutral. Advanced citizens will be high functioning individuals able to define their own identity. They will be able to constantly revise their relationships with their country, their ethnicity, their religion, their gender and their culture. Indeed this is the ideal for a high functioning individual. The world will represent a profoundly rich environment full of opportunity for such individuals no longer tied to outdated and restrictive norms.

I think most immigrants sense this state of affairs within Western countries and for the individual it is a rather good thing.

You haven't been listening again, have you?

You can't fight it PocketAces, you just have to embrace it. The individual egoist just has to make the best of the environment he finds himself in.

The problem with articles like this is they assume that all factors are fixed. There is no room to assume that an unseen factor could change everything. That could include a global pandemic that derails international trade to the appearance of startling evidence that oil is indeed self renewing and not scarce at all. Imagine how each and every economic assumption would be affected if something like that happened?

Mauldin makes the usual mistake about Japan. A stable or decreasing population is a great thing for wealth and lifestyle. He just assumes we all think it's a problem, but not all of us do.

Reading this article, one would be forgiven to think that the situation in Japan is bad bad bad.

Is that true? Is GDP per capita in Japan better or worse than in NZ (or US)?

If GDP is not increasing, or only increasing slightly, but population is declining, does that mean you need to import people just so you can say that you have increasing GDP again?

Personally I think Japan is a great model for the world to step back and stop the Ponzi scheme that eternal immigration perpetuates.

The only path to prosperity is better productivity, not importing more people.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.