Getting ‘bang for your buck’ is an important consideration when it comes to infrastructure. How many houses will be built, how many businesses will start, how many more customers will be served and how much employment will be created. These are the sort of beneficiary factors infrastructure providers want to maximise from their infrastructure spend.

Internationally there is a lot discussion of how very small public entities at the urban block or street level could provide benefits for cities.

This paper examines the question of whether these sort of micro-institutional arrangements at the street or urban block level are the fairest and best way to improve responsiveness of city housing supply and rapid transit ridership to rising demand for housing and transport services.

Renowned economist and Professor of Urban Planning at UCLA, Donald Shoup clearly articulates this question in an LA Times article titled - How L.A can gain housing (and transit ridership) without infuriating the neighbors.

In his paper Donald Shoup highlights the need for rapid transit to go hand in hand with a mechanism that allows the building of more housing in a way that isn’t a nuisance.

Should Los Angeles allow higher density housing in single-family neighborhoods near rail transit stations? Higher density will create more housing and increase transit ridership, but many homeowners view higher density as a bad neighbor. If a developer demolishes a single-family home to build a four-story box, the developer makes money, the new residents gain housing, and the transit system gets more riders, but the nearby homeowners get stuck with an outsized eyesore.

If all the neighbours affected, which depending on the width of the street and arrangement of plots within an urban block, could either be a street or a block, were beneficiary partners to the development scheme then the nuisance costs (factors like, loss of sunlight, privacy considerations, more competition for public car parking spaces etc.) could be internalised against development profits and benefits. Projects where the development gains are greater would be acceptable to the street or block and would therefore proceed.

International studies as documented by Robin Harding in the Financial Timesin an article titled Planning rules are driving the global housing crisis shows that planning rules add significant costs to house building.

Careful economic studies try to compare the cost of building to the cost of existing homes, or the price of land with planning permission to that without it. For example, as of 2002, Edward Glaeser and colleagues attributed half the cost of Manhattan apartments to planning rules. Christian Hilber and Wouter Vermeulen found English house prices could also have been 35 per cent lower in 2008

Research in 2017 found similar results for New Zealand cities.

This means that if the costs and benefits of new housing were better internalised significant savings could be shared amongst the various parties. Existing landowners, new residents, developers and transit providers etc all could receive benefits. What is needed is a mechanism to achieve this.

Donald Shoup’s recommended mechanism is graduated density zoning.

Here is the description of how graduated density could work in Los Angeles;

The Expo Line station at Westwood/Rancho Park, for example, is in the middle of a single-family neighborhood. Apartment buildings nearby might anger the current residents, but some cities are using “graduated density zoning” to solve this problem: It allows higher density, subject to limits, but also protects homeowners from unwanted development.

In Monopoly, players must buy four houses before they can build a hotel. With graduated density zoning, developers must assemble a group of houses before they can build apartments. The land remains zoned for single-family housing on sites of less than a given size, such as one acre. Only if enough homeowners agree to sell their adjacent properties for land assembly will the zoning allow multifamily housing on the newly formed site.

Homeowners can prevent land assembly by refusing to sell. Nevertheless, graduated density zoning encourages homeowners to join a land assembly because more units per lot means higher prices for their property, perhaps triple the value of a single-family house.

My concern about Donald Shoup’s proposal is that it gives ‘holdouts’ site assembly monopoly pricing power i.e. the last neighbour agreeing to sell for site assembly needed to trigger the increased graduated density zoning, which makes the development scheme profitable, will increase their asking price so they receive all the development profits.

I think graduated density would eventually lead to more houses being built near rapid transit compared to the alternative where site assembly doesn’t occur and intensification is much smaller scale. Graduated density though will be prone to delays and price hikes from holdouts so its ability to quickly produce more affordable housing (and more transit riders) would be limited in my opinion.

Source: missingmiddlehousing.com

I have a similar concern for Auckland. Recent Unitary Plan zoning changes were an improvement as they are more permissive. The Unitary Plan did not though provide a mechanism for neighbours and neighbourhoods to balance the nuisance costs of more housing bulk versus development gains from building more residential space. Arbitrary restrictions favouring stand alone homes remains the Unitary Plan default setting, even for areas zoned for apartment and terrace housing. Overseas in places like Tokyo and the inner suburbs of Houston (an area 20 km across) the default setting in zoning provisions are missing middle or apartment housing (and mixed commercial).

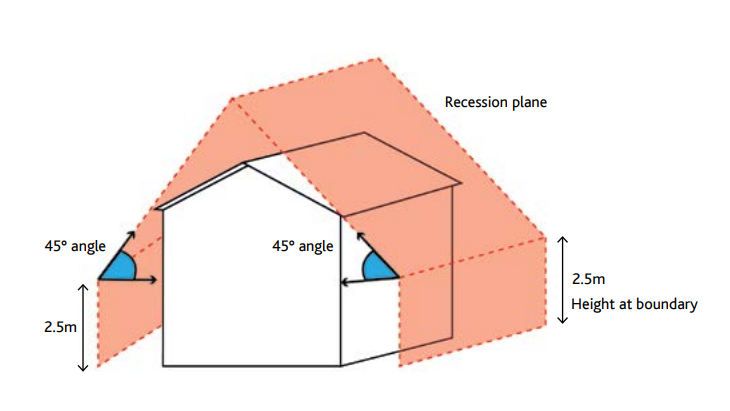

The Unitary Plan only made a minor change to the height at boundary zoning requirement -increasing it from 2.5m to 3m for areas zoned for apartment and terrace housing or mixed housing. Otherwise recession plane rules favouring stand alone housing and sausage flats were unchanged. Image from Auckland Council Unitary Plan 101 document.

The Unitary Plan does not provide the sea change that unlocks the potential of existing Auckland suburbs to become transit oriented walkable neighbourhoods with an influx of highly desirable ‘missing middle’ housing forms. The Unitary Plan is a hard constraint on more housing, more businesses, more customers and more employment for many parts of Auckland where there is strong demand to provide this activity.

Previously I have described Tokyo’s responsive housing supply and impressive rapid transit ridership numbers that allows commercial transit companies to profitably provide rapid transit services. First in an article titled - What is the secret to Tokyo’s affordable housing? Second in an article titled - Tokyo does not subsidise its transport system!

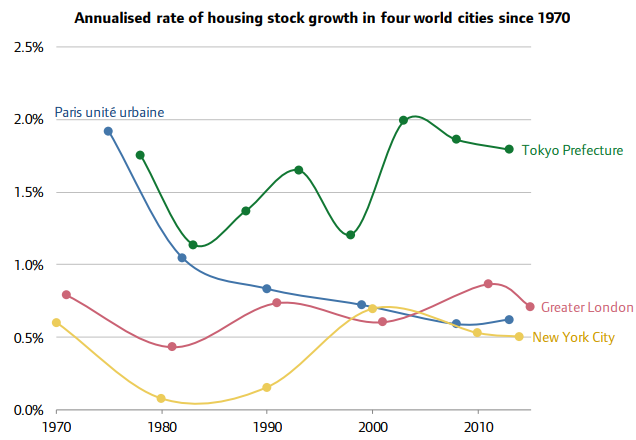

Graph from James Gleeson’s article How Tokyo built its way to abundant housing

Scott Beyer who produces The Market Urbanism Report has also written about Tokyo’s impressive Build, Build, Build Stategy, which he attributes to the 2002 Urban Renaissance Act.

Here is a summary of how the Act works;

Basic Operation Policy of Urban Renaissance Act in Tokyo

1. Project should be proposed by the private sector (take the full advantage of business ingenuity of private sector, the private sector shall hold the ability to conduct the proposal),

2. Obligation of rapid process of the urban planning procedure (shortened from two years to six months),

3. Proposal shall be individually examined, not by the uniform criteria,

4. Accountability of the private developer for the residents and neighbours, obligation to obtain the consent of at least two thirds of landowners.

The selection criteria of URED Area is as follows;

1. Whether the economical potential of the area is high enough,

2. If there are enough investors to fund the project,

3. If the proposal has enough potential to be realized,

4. If the program has high enough quality (first grade program) to meet the international standards.

Interestingly the Urban Renaissance Act only requires the consent of two thirds of the landowners for a development project to go ahead. So there is a mechanism to address the monopoly site assembly issue.

I have my doubts that the Urban Renaissance Act is the only factor behind Tokyo’s impressive build statistics. Japan’s planning system in general is much more permissive than Anglo-world cities as can be seen in this article. Another factor is Japan did not have a slum clearance or a garden city period where local and central government encouraged the movement of city dwellers out into suburbs and satellite towns. Japan instead had a institutional response of improving ‘slums’. Culturally this means the Japanese do not have hang-ups and prejudices against density that many Anglo-world residents have.

There are other variations for solving the problem of how to build more housing around rapid transit stations.

In California there is a Bill going through legislature that would allow transit provider Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) to ignore many local zoning regulations when it builds on its own land.

It is a good idea to allow transit providers to capture some of the economic activity generated around its transit stations by being property developers. This can align the rapid transit interests with the communities it serves. It also can provide a useful amount of revenue to the transit provider. Tokyo does this well with its competing passenger train companies. These transit infrastructure providing companies in effect ‘price in’ more housing and business activity.

Hong Kong’s MTR is also heavily involved in property development but without the competition seen in Tokyo, as it is a monopoly transit and transit focused property provider. MTR’s rapid transit system though is highly efficient with the world’s highest fare recovery rate of 185%.

The concern I have about BART gaining planning rights and Hong Kong’s MTR transit/property development system is the monopoly pricing issue again. BART and MTR are public or government owned entities, but that provides no guarantee this will stop them from exploiting their monopoly position. Hong Kong unlike Tokyo is notorious for its unaffordable housing.

Hong Kong’s highly profitable MTR could be a modern extension of the colony’s previous land banking practices. Professor Alan Evans writes about these historical land banking practices in his book Economics Real Estate & the Supply of Land (2004, P.185).

Hong Kong, as a Crown Colony, had a system under which all the land started off in the hands of the government of the colony. The sale of this land for development was integrated into the planning system, since the sale of a site was controlled by a contract which laid down how it should be developed, controls which would elsewhere be part of the planning system (Bristow 1984, Staley 1994). The example of Hong Kong, however, illustrates also that public land banking need not result in low land prices. Land prices in Hong Kong were notoriously high, and the government derived a considerable part of its income from land sales.

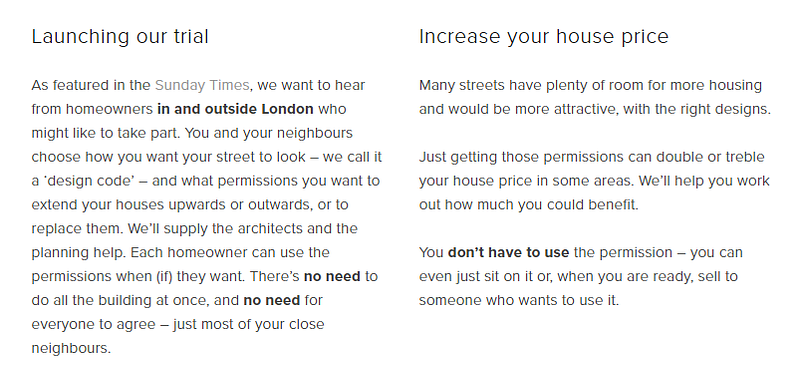

In the UK London YIMBY has a Better Streets proposal that if enacted would create a street level improvement district. Participating streets would be empowered to make their own building design codes. London YIMBY believes many city streets could be more beautiful with more homes.

These new houses would have a package of community amenities, environmental considerations, economic value and aesthetics that are desirable benefits to neighbours who are most affected by building more housing spaces in their street. The Sunday Times reported on the Better Streets proposal with an article titled - Are you a Yimby: Would you band together with your neighbours to transform your street?

I have written about a Master Planned Block proposal that I believe could improve New Zealand’s housing supply responsiveness in situations where rapid transit is being provided. This proposal is also in the same micro-institutional community improvement district ilk. Because of the wider streets in New Zealand and the larger sized residential blocks that would benefit from having more through lanes I advocate for block level improvement districts.

I believe Master Planned Blocks have some advantages over graduated density and giving monopoly transit providers planning permission status because it addresses the monopoly issue as well as balancing development gains against nuisance costs for neighbourhood communities. The intent is to increase competitive tensions in the same way that Japan/Tokyo does, which I believe will result in better and fairer outcomes.

There is some academic support for these various micro-institutional arrangements. Professor Robert Ellickson in 1998 wrote New Institutions for Old Neighborhoods in the Duke Law Journal [Vol. 48:75] where he advocated for the creation of a legal framework for Block Improvement Districts. The key paragraph being on pages 98 and 99.

Should a BLID (block level improvement district) also have regulatory powers? As Liebmann and Nelson both contend, there is a compelling case for empowering a block association to relax many of its city’s zoning restrictions. Nelson plausibly anticipates that a grass-roots organization would be more likely than a municipality to bargain to lift an inefficient land use restriction, such as a legal barrier to opening a daycare center. As a long-time proponent of the decentralization of land use regulation, I applaud experimentation on this front. Most zoning regulations mainly govern use allocations, building bulks, lot shapes and sizes, parking requirements, and other land uses whose spillover effects are limited. A BLID should be empowered to grant variances from these sorts of regulations, although perhaps not from the few zoning provisions (such as limits on extraordinary heights) that are aimed at preventing neighborhood-wide negative externalities.

This discussion may seem arcane and convoluted but transport and housing provision are hugely important problems in many modern cities. Any potential remedy should be fully investigated.

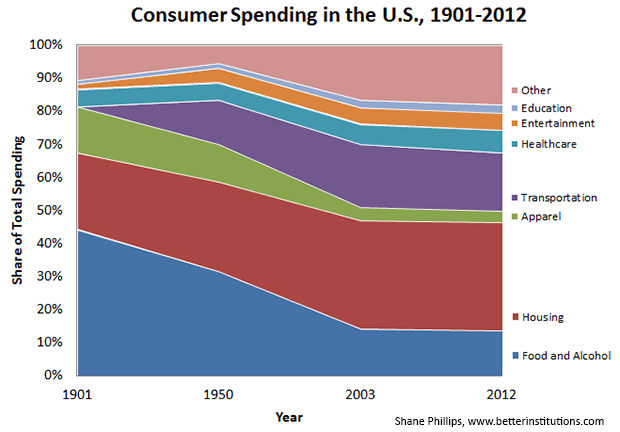

Source: Housing & Transportation Costs Have Become a Growing American Burden

Housing and transport costs have become an increasing burden for consumers in the US over the past century. This means it has become increasingly important that policy settings ensure housing and transport supply is responsive to demand.

A similar problem of rising transport and housing costs exists in New Zealand too.

For example recently David Chaston at the New Zealand business sector website interest.co.nz analysed median household consumption patterns in New Zealand. This showed that increases in housing and transport costs were negating wage increases for renters in particular. There was concern this reduction in discretionary spending is a factor behind the loss of business confidence in New Zealand in 2018.

In conclusion a remedy for the big society-wide problem of rising housing and transport costs would be for policy makers to look at how the smallest units of public cooperation can help.

This proposed remedy would work best as part of a wider urban growth agenda that addresses issues like urban and spatial planning, infrastructure funding, congestion pricing and legislative reform.

The New Zealand government has released a Cabinet Paper with a proposed urban growth agenda.

New Zealand’s main opposition party - the National Party has said that its RMA Reform Spokeswoman Judith Collins is working on an RMA bill to reform planning rules for the country. This policy work will be publicly released in 2019 as proposed legislation which the National Party will take to the 2020 general election.

We are really clear that if you want to deal with land supply, you need to have significant RMA reform.

Collins says National is still in the early stages of drafting the legislation but has promised the bill will “return the concept of property rights to owners of the land.”

Empowered micro-institutional communities that maximise benefits to existing residents and newcomers in response to infrastructure investment would be consistent with these broad reform approaches. Especially if that allows enabling infrastructure to be more efficiently provided.

This is a repost of an article here. It is used with permission.

37 Comments

Very interesting article thanks Brendon.

One clarification - the Unitary Plan has an alternative height in relation to boundary control for the front 20m of sites, which is much more enabling than the standard 3m + 45 degrees rule.

You might be interested in this stat - 50% of properties in the Terrace Housing and Apartment Building zone that have obtained building consent approvals in the past 12 months were for detached homes. That is just incredibly wasteful, given the zone is anticipating 5 storey apartments.

There need to be more incentives for higher density development in this zone, and more disincentives for lower density development in this zone.

I think the way Auckland Council taxes new house building is also a disincentive for these medium density zoned areas. The costs for new infrastructure etc should be charged per square meter of land not per new residence. The whole developer and financial contribution system is intellectually bankrupt.

Nice work, as always, Brendon.

I agree regarding the intellectually bankrupt statement - we do need another way.

I was wondering whether you (or anyone) have yet done any analysis on how the zone changes in the UP have changed land values wrt to the re-zoned (i.e., amended density zoning designations) land parcels?

I know it is early days, so the sales data is likely limited in terms of making those comparisons.

I'm interested in the idea of 'betterment' and 'worsenment' and its potential use in rating systems, which sort of dovetails in to your considerations wrt incentives regarding urban renewal/regeneration.

A few paragraphs into this article there is some info on the gains to existing land owners from the Unitary Plan

https://medium.com/land-buildings-identity-and-values/can-great-design-…

The problem with Betterment Taxes is how to stop it being a tax on new housing. I have not seen any examples of it being successfully implemented. I think the better way is to compete away the land banking gains.

Brilliant, thanks! You are right - the literature on it is very thin and I've yet to properly research its application. Thing is, GIS systems have become so much more sophisticated of late, such that implementation (i.e., near 'real time' update/re-calcuIation of the tax burden or tax benefit, as zoning and/or infrastructure improvements are recorded on the database) I believe would become much less onerous than it might have been in the past. Perhaps that is why it isn't used much in practice?

In many cases, new infrastructure is a benefit for many and a burden for a few - it's the tax equity issue that is of interest to me (which I know isn't your area of interest wrt this discussion). The new Kapiti Expressway is a great example - 20 minutes off the drive/commute to Welly for everyone district-wide - but causing increased traffic noise (and hence much, much lower property values) for the handful of residents located in close proximity.

An even bigger benefit (than that experienced by most district-wide) has been the gain to residential properties on the old SH1 road (the benefit - less congestion/less traffic noise) but the commercial properties on that same road experienced the opposite (a burden - lowered traffic count).

I imagine such a methodology in calculating rates would dramatically decrease tax/rates on new housing on the periphery (that which is furthest distance from existing commercial centres/infrastructure); it would decrease tax/rates for those with new PT/roading/prisons/tips/stadiums etc. infrastructure over their back fence; but increase it for those within walking distance (but not nuisance distance) of such infrastructure developments.

Just thinking out loud though!

The more I have looked into permission to build (because being able to build more houses is fundamentally the long term fix for the housing crisis) the more I have realised how imperfect the system is.

I think the presumption should be landowners have the right to build and as a society we should have a variety of mechanisms to manage the nuisance. Primarily that has been with local government regulation i.e district plans etc. In Auckland's case the Unitary Plan.

But these plans are rather arbitrary -so if a smaller group -like a set of neighbours can agree on a better way to manage their local nuisance issues then a mechanism for them to opt out of District plans should be provided.

A set of neighbours could get together under the current unitary plan and either apply for resource consent, or go for a plan change. Nothing stopping them under the current system.

Yes but to do it under the current regulatory system would be a one-off ad hoc arrangement. And it would be hugely uncertain with high transaction costs.

Applying for resource consent or a planning change would be a bit like not having any Body Corp laws and every single apartment complex making up their own collective contract arrangements.

Add in the factor that local government may not cooperate with this sort of neighbourhood activism then I do not think what I am proposing and what theoretically could happen under the current system is the same.

So yes Fritz theoretically you are right. But in practice if the law is not clear and predictable then a collective arrangement such as I am proposing is unlikely to happen.

Hi Brendon. What do you mean by "their local nuisance issues"? What kind of nuisances (might they want to opt out of DP rules as a means to resolve) would you provide as examples?

Nuisance as I am using it is a very old legal term.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuisance

Nuisances which neighbours may not be bothered about, especially if they are jointly part of a local development scheme that has design features which add value might be -Car parking minimums, setback requirements, recession planes, height limits (up to extraordinary heights that could be a nuisance to entire suburbs), commercial activity..... all sorts of stuff that District Plan have arbitrary rules about. These rules are made by technocrats -when it might be better for locals to negotiate some of these nuisances amongst themselves.

In parts of Auckland you can kind of see this happening organically as 'disobedient architecture' where garages are converted to residential spaces, decks are covered to use as extra social spaces, sheds become sleepouts or offices. Houses are jacked up to make space for commercial workshops....

Maybe instead of stopping these 'slums' we work with them to improve them...

Check out the following research -there are actual examples of this process happening.

Weber, P. (2018).Plan B: An incremental housing project in Auckland.

http://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/4326

A History of Town Planning -Productivity Commission P. 6

Betterment Fund

The “Betterment Fund” was another key aspect of the 1926 (Town-Planning) Act which failed in practice. The intention was that each local authority should set up a Betterment Fund from which to meet compensation

claims and other expenses incurred under the Act. The fund was to be provided by the payment to

the local authorities concerned of one half of the “betterment increase”(defined as the increase in the

value of any rateable property as is attributable to the approval of a town planning or an extra-urban

planning scheme, or to the carrying out of any work authorised by the scheme). However no

betterment was ever collected, apparently due to difficulties of calculation and collection, and the

concept of a Betterment Fund was omitted from the 1953 Act.

https://www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/using-land-draft-r…

P.S Compliments and upticks for your article Kate. I am at a family event so cannot give any more detailed feedback.

https://www.interest.co.nz/users/ryan-greenaway-mcgrevy

Auckland Council Chief economist unit have done similar stuff, also.

Yes, exactly what I was looking for - thanks.

Fritz re: "You might be interested in this stat - 50% of properties in the Terrace Housing and Apartment Building zone that have obtained building consent approvals in the past 12 months were for detached homes."

I think the default setting of our district plans etc makes detached homes the easy low risk option and other housing types more difficult a process to go through. So it doesn't surprise me.

That statistic also makes a fool out of Auckland's chief economist claims that the Unitary Plan up-zoned 1 million extra houses. That 'fact' can only be assumed if every up-zoned plot was built to its maximum building intensity. A completely implausible assumption. But that is economists for you.

Have you heard the joke about an economist, a physicist and a chemist stuck on a deserted Island with their only food being a can of baked beans but they had no can opener.

The physicist says "I have found a sharp rock and by my calculations if I throw the can 5.2 metres in the air and it lands on the rock, that is the correct amount of force to break the seal on the can."

The chemist say "that is too dangerous, if you throw the can too high we will all be splattered with baked beans. I have started a fire and my calculations are if we leave the can in the fire for 8 and half minutes the can seal will gently break and we will have cooked beans."

The economist says -"no, no, no that is too dangerous. If the fire is too hot the can will burst open with huge pressure and we will be covered in boiling hot beans. I have a better idea -lets assume we have a can opener."

This essay is full of insights, thank you. Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava are good authors on Tokyo’s evolutionary history. They use a term “incrementally developed slum”, which sums up part of what you are saying. Another big advantage to Tokyo is that they have successfully preserved “street space” of a higher intensity than most cities around the world (see the report “Streets as Public Space and Drivers of Urban Prosperity” from the UN Habitat Program). I am suspicious that continued redevelopment to ever-higher intensities in other cities marked by much lower street space, will be as efficacious. Auckland NZ gets some paragraphs devoted to it by the UN authors because it is such a Kafka-esque outlier on the low side, for street space, at least in the First World.

That is a very interesting link you provide re Tokyo’s competing railway companies.

City lessons from private rail operators of Japan - Gehl

https://gehlpeople.com/blog/lessons-city-private-rail-operators-japan/

I hadn't read that, when I posted my take on Tokyo:

Tokyo’s unique path to density and affordability

https://medium.com/@philhayward/tokyos-unique-path-to-density-and-affor…

It is very confirming; what I argue in the way of benefits to Tokyo, goes beyond what the Gehl Blog author says; I say that the competition between these enterprises for residents and trip attractors, which fits in with ridership maximization, reduces housing prices and floor space rents in the entire market. This has to be a factor in Tokyo’s unusual (for a megalopolis) affordability.

The problem with Master Planned blocks and similar schemes in cities with an affordability problem and Anglo cultural histories, is that the motivations are quite different to those of Tokyo residents who see each new phase as an opportunity to improve their neighborhoods. The Japanese churn their housing stock incredibly rapidly anyway, possibly for cultural reasons of love of things “new” and hence more clean and hygienic.

http://www.archdaily.com/450212/why-japan-is-crazy-about-housing

“…Houses in Japan rapidly depreciate like consumer durable goods — cars, fridges, golf clubs, etc. After 15 years, a home typically loses all value and is demolished on average just 30 years after being built. According to a paper by the Nomura Research Institute, this is a major ‘obstacle to affluence’ for Japanese families. Collectively, the write-off equates to an annual loss of 4% of Japan’s total GDP, not to mention mountains of construction waste.

And so, despite a shrinking population, house building remains steady. 87% of Japan’s home sales are new homes (compared with only 11–34% in Western countries). This puts the total number of new houses built in Japan on par with the US, despite having only a third of the population…”

And:

http://freakonomics.com/podcast/why-are-japanese-homes-disposable-a-new…

The lack of street space is a huge problem for Auckland and other cities in NZ. The report you refer to Phil can be accessed here. http://mirror.unhabitat.org/downloads/docs/StreetPatterns.pdf

This research indicates that walkable and permeable urban areas should have intersections for active mode users (walkers, cyclists etc) in grids or similar shapes of less than 100m square -giving at least 100 intersections per square kilometer. Auckland only has 72 which makes for an inefficient urban form, impacting on congestion, public transport and a lack of local active mode accessible commercial activity. Efforts should be made to correct this poor street pattern.

In many places in Auckland to travel by the road from back door neighbour to back door neighbour could be more than a kilometer.

I think this lack of common good roads could be partially corrected by more through lanes, which could be provided by Master Planned Blocks. In much the same way that Lord Bloomfield provided attractive lanes and parks to add value to the Bloomsbury housing area.

To incentivise this type of Master Block Planning a public fund could be created that buys these new lanes for the public good.

Nice essay by Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava. Thanks for the reminder Phil

http://www.urbanlab.org/TheVillageInside-EchanoveSrivastava.pdf

Good article as usual Brendon. My question is whether some or all of this can be done now under the UP and if not what is the minimum change needed? In other words can we figure out ways within the current rules to get small block redevelopment happening? If there are financial gains to be made, it should be worth someone's while to be the facilitator for the development. Maybe it does require the council to change its policy settings so that the default is for such developments to be approved and hence the regulatory barrier is minimised. Maybe it needs a developer or an agency to jump start the process

Hi David, here is my ideas on how to minimise regulatory and transaction costs for small block level improvement districts -i.e one residential block or smaller in size.

Proposed Master Planned Block activation procedure:

1. Central and local government supports the concept and gives some funding to master planning agencies or an Urban Development Authority to facilitate intensification in particular areas.

2. These master planning agencies conduct neighbourhood meetings to advertise the benefits they can provide.

3. If a residential block expresses an interest in becoming a Master Planned Block and has the support of over half the residential landowners then a process is started.

4. There is a set timeframe for submissions on what sort of design values are important.

5. Local government also submit on what would benefit the wider community, such as, public through lanes, walkways, bike lanes and particular sewer and stormwater requirements, etc.

6. The master planning agency is given time to develop a conceptual master plan design, an estimated construction budget, market value assessment etc, which they present back to the residential block community and to local government. The agency can also present a study on how the residential block will likely intensify without master block planning.

7. A crown agency (something like a Queensland Land Court) assesses whether local government requests have been adequately provided for in the master plan. Local government do not get to make further requests.

8. Residents are then given a simple yes/no binding option of whether to proceed or not, with 80% agreement being the minimum threshold required.

9. If there is unanimous support then the master planned block can proceed directly to the applying for finance and construction stages.

10. If there is greater than 80% support but less than unanimous agreement. Objectors are given a time limited period to join the scheme. It is explained that the Master Planned Block has gained planning authority over the entire block, so any future building or subdivision alterations would require the approval of the Master Planned Block. This is to discourage holdouts from speculating they can wait and negotiate a higher monopoly price. At the end of the opt in period if there are any landowners who choose to continue to opt out, the Master Planned Block should attempt to plan and build around them, in the first instance.

11. Compulsory acquisition could be divisive to the community and as such should be rarely used and only in the last resort. It should require an application to a seperate crown agency with a legislative ‘taking’ power. This power should only be used in cases where there is a very, very small number of holdouts, who because of their location, shape or size of their land they are stopping a scheme that has overwhelming wider social benefits. There should be checks and balances protecting the interests of landowners whose land is being compulsory acquired, provided by this separate crown agency.

This plan is taken from my paper here.

https://medium.com/land-buildings-identity-and-values/can-great-design-…

Nice piece, Brendon.

For me your paper highlights a crucial question concerning urban development: who defines urban shape and content? Public authorities quite unequivocally exert most of that power currently. But that power, when poorly exercised, comes at the massive cost of unaffordable housing and the subsequent impacts on the economy, health, education and other outcomes. It can also put a direct brake on economic well-being through sub-optimal urban layout and excessive accommodation costs for business. Aesthetically we have ended up with a bland uniformity of urban appearance from one end of the country to the other.

You have advanced a great way in which residents could bypass planners to create denser housing while still mediating nuisance internally and externally. So we could see some of the power and some of the creativity shift back to the actual residents. Conceptually, I can't see any reason why developers and/or residents shouldn't organise the layout and the permissible activities within a sub-boundary of a city.

The advantages of allowing freedom at the micro level are obvious. Then we would find out whether people are or are not OK about having commercial activities sprinkled among residences. We would find out whether there was an appetite for medium-density housing. We would find out what amenities by way of green space and community facilities people would pay for by choice. We would find out whether we really need two car parking spaces per property. We wouldn't need to rely on a handful of technocrats making their best guess at the answers to such questions.

Will it happen?

While I cannot see any statutory reason why it couldn't happen I don't think any council would willingly allow this freedom.. The RMA does not require a council to put site coverage, setback or height rules in a district plan. It also only has to restrict activity in as much as an activity has negative impacts on the physical environment. So an island of comparative permissibility is possible in the current legal environment. But there is only downside for councils as institutions regardless of the benefits for the wider community.

Firstly, the incentives for politicians and staff are pretty much aligned dead against freeing development up. In general, there are precious few opportunities for a councillor to "leave a legacy". Currently, playing around with the district plan (with a sub-major in alcohol policy) is about it. Leaving it to private interests to design parts of a city could lead to favourable publicity for others while marginalising the council. And, of course, for staff more planning rather than less is beneficial for their careers.

If thats a bit cynical the second reason is more compelling. All councils would consider allowing planning freedom to be a risk to the council. Although they don't have to, councils often feel pressured to step in and pick up the pieces if a development goes sour. But the only way these block-level units could ever deliver city-wide benefits is if they are allowed to fail. Councils would also definitely feel the pressure on transport and water infrastructure that comes from unsequenced development. Councils have got very used to having high degrees of control over infrastructure spend extending out over many years even decades. I suspect they would be very uncomfortable with having to be flexible for a change.

Many councils also have experience with body corporates asking councils to take over their infrastructure. Councils would have big questions over the sustainability and longevity of block-level BC's.

I do think a council could agree to a development if an organisation with a track record was the promoter. For example if the Sallies wanted to do a block-level medium density social housing development I could see that going through on a case by case basis. But a general freeing up? Not so much.

To make any of these schemes work it would take a combination of statute requiring councils to allow this style of development backed up by an audit process that ensured councils implemented the legislation.

Although they don't have to, councils often feel pressured to step in and pick up the pieces if a development goes sour.

While they remain the providers of building inspections and the monitorers of resource consent conditions, I think they do have a liability in law - as seems to be the case with respect to the Bella Vista development in Tauranga, for example.

Perhaps its time to re-think who provides those services and let a contestable market for them develop - then council's would be far less risk averse wrt development generally.

PS I don't think Wellington City is bland - it does seem to me to be a very well planned city. Lovely to look at from all angles, well planned CBD, great waterfront spaces.

Bella Vista is a case where the council actually were deficient. What I am referring to is cases where a development has been consented and has proceeded but, for reasons that have nothing to do with the consent the development has gone belly up. Having worked for a council for some years I know that they feel some kind of odd need to to make things work out. God alone knows why.

PS Mirimar, Kingsland, Karori, Johnsonville etc etc etc

Genius comment Donald. Thank you.

Great comment, Donald, and from inside knowledge - a perspective so often missing. I fully agree: Councils, their unelected staffs and what we refer to in IT as 'incumbent inertia' will fight anything which lessens their monopoly and their power.

It will take top-down action - an iconoclastic legal change to the RMA or to the LG Act, perhaps - to dismantle their cosy little eyrie.....

Perhaps that's what Judith Collins is - er - Planning?

Brendon - like many I read the newspaper from back to front and I've read the comments before reading your article. These comments will be massaging your ego far too much so I'll just say 'load of crap - couldn't be bothered reading it'. But on 2nd thoughts just reading Phil's info about "Houses in Japan rapidly depreciate like consumer durable goods" means I will be reading it slowly - I ought to be in my Auckland garden this morning so I'll blame you when the wife asks me why the plants aren't potted. PS what was in the heads of Auckland's founders - why build a city where the island is narrowest; why provide gardens where the ground is like sucking plasticine in winter and concrete in summer? Time I moved to Christchurch.

Lapun feel free to blame me if that helps the relations with the wife; )

I do feel kind of guilty that what I have written is so arcane and convoluted -but that is where the evidence points to. Lots of people have had input into these ideas over the years, including from this website so I don't feel a particular ownership over the concepts or big headed about them.

Improving house building in response to rapid transit investment will help address the housing crisis but it is not a silver bullet, so I am also not big headed in thinking this is 'the solution' for the housing crisis. But it would be something relatively easy to implement that would help.

Re Auckland -did it have founders? Its history seems to be more about a lack of planning. It is a pile organically arranged building material in a beautiful location with lots of natural advantages isn't it? Perhaps Auckland needs to embrace its organic growth culture to rearrange its pile of building material so it more beautifully fits into the environment whilst also being able to accommodate more people?

OK I like Auckland otherwise why live here. It has many wonderful features but the dumb decisions that have been made in the past are almost beyond belief. They include:

a. Failure to use standard guage rail and reserve land so single tracks can be increased to double. Add in curves that were too tight. Excusable when building a railway into a big existing city but not a small but obviously going to grow city.

b. Build an airport without reserving land for dedicated high speed access. You can argue whether it should be rail, bus, lightrail or horsedrawn stagecoach but that land should be just sat there waiting.

c. Build a bridge with only 4 lanes on the assumption that it would have no effect on where new suburbs would be built. Attach a 4 lane motorway so expansion is as messy and expensive as possible.

d. Build western motorway without a dedicated busway - surely they ought to have learned from the success on the northern busway?

When you live with such mega-dumb past planning you have to be cautious of all planning.

e. Surrounding the CBD by a moat of motorways in a way that removed thousands of houses and cut off the CBD from its walkable/bikeable inner city suburbs.

f. Only implement the motorway parts of post WW2 urban transport plan. http://www.thesustainabilitysociety.org.nz/conference/2007/papers/HARRI…

g. NZ's societal ambivalence and a lack of focus to its cities. Rather a preference for promoting the countryside and our scenic areas.

Lapun most people are not aware that in NZ town and city folk were the last group to get equality of the vote in 1945. Before that a country quota required rural electorates to be around a third smaller than urban electorates, thus making rural votes more powerful in general elections.

It is debatable if the quota had much effect on electoral outcomes but it was certainly an indication of NZ societies relatively recent poor attitude to our cities. Is it surprising that this poor attitude translated to poor decisions?

You don't debate my (a) to (d) which I pulled out of mid air - I'm sure a considered analysis would produce better examples of planning disasters.

This year on holiday I visited a few European cities and my sight-seeing was influenced by reading some of your town/city planning articles. Vienna with its world's most liveable city status - certainy had motorways and so did most of the big German cities (well less big than Auckland).

(e) What cuts off Auckland CBD from inner city suburbs is not motorways (I will admit they are bad) but slopes, decline in fitness and distance to walk (say anything over 2.5km), simply dangerous to cycle (admitedly well designed cycle / walkways built say 50 years ago would have made a big difference), an aging work force, increasing obesity, too often wet.

(f) haven't read your 22 page link and given its origin maybe not unbiased source but I am sure you are right. So sure I would have read all 22 pages if you had suggested the opposite.

(g) vague.

An adjustment to electoral laws before even I was born carries little weight. The romantic appeal of the country to the city dweller is not unique to NZ (I love Country Calendar). America is the best example with its cowboy culture but France still has its farmers with excessive political clout. It is not just a folk memory of where you or your parents or grand-parents came from; we know patients recover more quickly in hospital if they can see greenery from their ward windows - the countryside has an appeal. City dwellers holiday in the country and rural citizens often holiday even farther from habitations (hunting & shooting).

I have no problem accepting the move from rural to urban living. The more spare time we have the more time we want to spend with like minded people and that means a city. What Austria, Bavaria, Switzerland, NE France and S of France suggest to me along with contemplation of the mathematics underlying agglomeration theory (curse you for introducing me to that word) is the idea of the right sized city. All things being equal a city needs a minimum and a maximum size for best lifestyle; Toulouse, Nuremberg, Frankfurt and Basel seem to give their population economic opportunities along with a good lifestyle. Growing larger seems to create congestion problems.

Ok if you want a debate;

re: a. All city public rights of way and parks need to be laid out in advance of development because after the fact it is very difficult to impossible to change. This is one of the basic pillars of the Making Room paradigm.

b. Same point as a, stop repeating yourself ;)

c. Induced demand is a major in urban development but the NZTA economic manuel which is used to estimate BCA's doesn't recognise it -how stupid is that?

d. Same point as a +b,-it is stupid when will we learn?

e. I am not anti motorways -Finland where my wife is from has better motorways than NZ and it has a similar pop and size. It is the dominance of motorways and roads in NZ to the exclusion of all other transport modes that is weird.

f. You should read the link -it is a genuine academic type paper that describes Auckland's largely forgotten transport history. As far as I can tell it is quite factual.

g. The country quota attitude I think is more intensely felt here in NZ than any other country around the world I have been.

It is still an attitude held by some influential people. For example Gill Cox a NZTA board member a few years ago had this to say about my home city.

"Boiling it down, it starts with the economic truth that the fates of Christchurch city and its rural hinterland are absolutely intertwined. “Christchurch is a market town,” says Cox simply. “Christchurch would struggle even to have a reason for being if Canterbury were not there. The economic driver is not the city but the region.”.....Cox says before the earthquakes, Christchurch had become somewhat politically disconnected from this fact. It had dreams about being a world-class small city riding the high tech “knowledge-wave” — a mini-Copenhagen at the bottom of the world.

Of course, says Cox, Christchurch should still want to do its best on this score. But really, as a long-term strategy, it just pits the city against every other city….

Christchurch has to concentrate on its true natural advantages, says Cox. And when it comes to NZIER’s analysis, these are simply the two things that Canterbury can be a premium-quality food basket for the world, and that Christchurch can get a free ride in being the tourist and freight gateway for the South Island.

Again, news that is no surprise for those who are in business in Canterbury. But Cox says our politicians and the general public may not have the same tight focus on how the region’s bread is buttered…."

Note how in Gill Cox’s opinion Christchurch is a market town not a city, that economic opportunities lie in rural not urban areas (with the exception of the city being a freight and tourist gateway) and that wanting to be a diversified economy like Denmark’s is ‘disconnected’ and ‘dreaming’. I don’t think Gill Cox speaks for all businesses –I think many city-based businesses would be surprised about his bias. Gill Cox’s comment that the general public cannot focus on how the region's ‘bread is buttered’, is in my opinion code for saying that the region’s economy should be directed by ‘experts’ such as himself and that democracy and debate is unnecessary.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/news/75003586/canterburys-basket-of-o…

Didn't really want a debate - just think we agree that bad planning has a long history and causes major pain and costs today. We need to avoid as many planning failures as possible and that is why I read your articles and I'm delighted you and a few others make this effort. Otherwise it is all left to self interested parties.

I found the quote from Gill Cox interesting. His point about 'market town' was for emphasis not literal and I think there is some mild truth in what he says however your point about who is the 'expert' and democracy is very well made. If heaven forbid Canterbury disappeard then Christchurch would survive as does Singapore. I think you might win that argument by simply compaing the working population or urban Christchurch with the working population in rural Canterbury (adjusting for the commuters) - I'm guessing Christchurch workers outnumber workers in the rural areas and do so dramatically. The rebuilding must be giving your planners plenty of chances to put in dedicated public transport routes and safe cycle paths. But it is not so much the good things they do as the decisions which restrict future options that bother me.

Brendon: we were persuaded to vote for the big city so big scale planning could procede. You are now arguing for planning decisions to be made by small scale neighbourhood communities. It makes sense but you are taking on a bureaucracy that will be very unwilling to lose its arbitary power. We need more time to see how well the UP is performing but my one conversation with a surveyor several months ago had him say 'after 35 years in this business we cannot predict how the council consent body will react; they are inventing new objections yet also approving buildings that we would never have contemplated proposing.' This worries me; NZ is famously non-corrupt but when there is serious money involved and decisions are seen as being arbitary then I am sure corruption will occur eventually. It is a classic example of a breakdown in the famous Kiwi fairness.

I like your idea of ask the neighbours, get 2/3rds to approve and then go ahead. Obviously there are rules that have to be enforced: stormwater, wastewater, blocking others access, fire hazard, etc, etc. These ought to be clear and virtually automatic. Where it gets fuzzy is when you discuss recession plane rules and that is where your idea would work. Take a simple example - because of the slope of the land and the alignment with the midday sun if I change my 1960's one storey house to two stories it would impact on my neighbour considerably but he could replace his two storey house with three or even four storeys without having any impact on me. If the council's recession plane rule was used as a base point for discussion and it was then left to neighbours to agree the system would be more flexible. Of course you can never get everyone to be happy but just being involved would improve matters greatly.

Lapun I think small groups are more likely to come up with a creative solution that takes into account all the variables -especially the unique site specific aspects of slope, block shape, views, prevailing winds -the cold easterly has a big effect down here in Christchurch etc.

I am not advocating getting rid of the 'big city' or the UP, rather that there should be a clear process to opt out if the neighbourhood agrees to a better plan. Really it shouldn't be a big deal. It should be a basic freedom to be able to do this...

Lapun if you are concerned about property related corruption. New Zealand has been there and done that. 19th century Auckland was particularly corrupt. Check out the RNZ podcasts on Thomas Russell and James Prendergast. The links are at the end of this paper.

https://medium.com/land-buildings-identity-and-values/rupture-2e7f66e20…

I lived in Port Moresby and know the Port Moresby town planner (a highly honest guy working in a politically corrupt city). Yes I am scared of corruption. It is my children and grandchildren who will live with its results. I hadn't heard of it in 19th Century Auckland but I'm not the least surprised. Kiwis need to be alert - set up systems that are anti-corrupt and stub it out before it starts. Pls don't think "it can't happen here" because it can.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.