This is a re-post of an article originally published on pundit.co.nz. It is here with permission.

'Newsroom' recalled Édith Piaf’s ‘je ne regrette rien’ to head an article in which Don Brash expressed much the same sentiment.

Brash opened up his defence of the policies with which he is associated with ‘Looking back on the six years of Rogernomics, I can think of almost no economic policy of that era which should have been done differently.’

He begins listing examples of market liberalisation. I broadly agree. Indeed, I was arguing for it publicly in the 1970s when those with wiser heads kept them well below the parapet, fearful of Muldoon knocking them off. (See, for instance my Economics for Social Democrats, a 1981 compilation of Listener columns.) In his memoir, Saving Labour. Michael Cullen agrees.

Ideology aside, the necessity arose because the increasing diversity and complexity of the economy meant that it could no longer be managed top-down from the centre, as it had been during the Second World War. Not only was there more choice (if you had the income) and improvements in quality (not well measured in the statistics) but, following the liberalisation, the economy became more flexible. That may be the reason that the response after 2008 to the Global Financial Crisis was shorter than one might have expected; flexibility was a major reason why the covid shock was not as damaging as expected.

However, Brash is on less firm ground with the rest of the policies. He does not mention the eight years of stagnation which Rogernomics precipitated – unique in our history for being the result of self-induced internal policies rather external shocks. During the stagnation unemployment rose to a postwar high, and it seems likely that about half of the labour force became sufficiently redundant to register with the Department of Labour. (Perhaps the shakeout was necessary but there was little support for the unemployed, and virtually no attempt to use the redeployment to build up the skills of the labour force).

Brash reports in his memoir Incredible Luck of ‘exceptionally rapid growth in the early 1990s’. The statistical evidence does not support him while the subsequent economic growth rate after the economy began growing again was much the same as the underlying one before the stagnation. (Fairness requires mention that Brash is proud of presiding over the Reserve Bank as inflation was reduced to low levels – the sole Rogernomic macroeconomic achievement. It was not only monetary management which did it, but the flexibility in the economy which the liberalisation generated together with the international disinflation.)

Neither Brash’s article nor his memoir mentions the privatisation of public monopolies, such as Telecom, without any regulatory restraint so that the purchasers made supernormal profits while consumers and efficiency suffered.

His discussion of the distributional impact of the policies is curious.

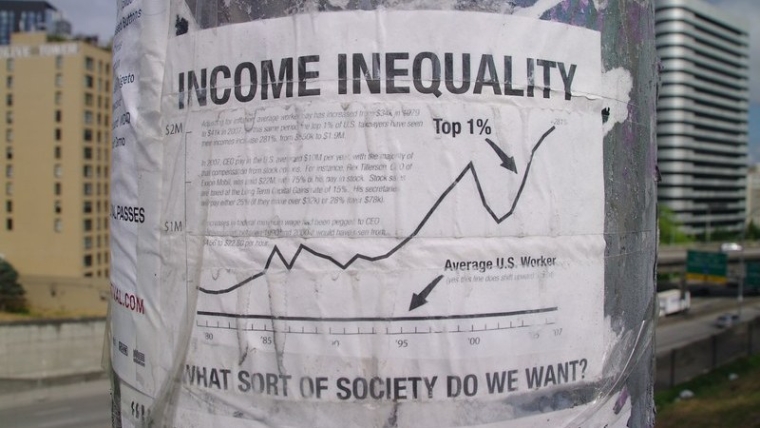

But what about the effects on income inequality of these reforms? If the numbers are taken at face value ... there was a reasonably significant increase in income inequality after tax and benefits during the late 80s, with a broadly unchanged measure of income inequality after tax and benefits in the 30 years since – some years a bit more unequal, in some years a bit less unequal. [The elision is a caveat, I’ll come back to.]

First, the total increase in income inequality was also the result of measures taken in 1990 and 1991 by the National Government who argued that they were necessary to fund the Rogernomics tax cuts, for Labour left office with a large ongoing fiscal deficit.

Second, we may wonder whether the distributional changes were ‘reasonable’. The facts are that the top ten percent experienced a one-off average real increase of 25 percent in their after-tax incomes from those measures, while those at the very top gained even more. Meanwhile the thirty percent at the bottom had no real income increase for two decades (while the incomes of those at the top continued to increase with the economic growth following the end of the stagnation). Whether this was a ‘reasonable’ change in the level of inequality I leave others to judge.

The statement that there was not much change in after-tax household income distribution after 1991 is broadly correct, with one exception. The National Government’s ‘redesigning of the welfare state’ both cut social benefits (to pay for the tax cuts for the rich) but also indexed benefit rates to consumer prices rather than general incomes so the beneficiaries did not share in any rise in prosperity. (The Ardern-Peters Government restored the indexing to wages in 2019, but by now benefits were at a much lower relative level.) There is no mention in the Brash article of the redesigning of the welfare state from the McCarthy vision of the welfare state, aiming to enable everyone ‘to participate in and belong to society’ to the minimalist one, more like the American vision. People suffered as a result, Don, people suffered; they were not nearly as lucky as you.

The caveat to his statement was that ‘there are some good reasons [in assessing the inequality change using the current statistics] for not doing so given the radical change in the tax system in the late 1980s’. There is no further explanation and it reads like the standard truthyism that ‘since I don’t agree with it, it must be wrong’. I agree that there are problems with the data measurement, but I have subjected it to various tests and none seem large enough to suggest a different story.

Brash’s statements are important, because Rogernomes have hardly defended what they did. This article and Brash’s memoir are the only examples I know of. (Because of the lacuna I had to construct a defence in my Not in Narrow Seas – chapters 55 and 56 – but I am hardly one of them.) You can be sure that had the neoliberal policies succeeded, the Rogernomes would be loud in their self congratulations. Their silence, in Brash’s case in the key areas of macroeconomics and distribution, tells you that even they think they failed. Yet the consequences of their measures haunt us to this day.

Brian Easton, an independent scholar, is an economist, social statistician, public policy analyst and historian. He was the Listener economic columnist from 1978 to 2014. This is a re-post of an article originally published on pundit.co.nz. It is here with permission.

23 Comments

Interesting conclusion. I don't think any of the politicians of that era have been silent - almost every single one of them supports the reforms with a couple of exceptions.

Reading The Ninth Floor with Guyon Espiner what's most striking is that Palmer, Moore, Clark, all agree the reforms were necessary - it's Espiner who constantly challenges and questions the need for reform. When he found a kindred soul in Jim Bolger who said they went too far RadioNZ ran a piece about it - seemed Espiner did find what he was looking for in the end. Same story with Bassett, Douglas, Prebble, just about all the Ministers from that government are on the record as supporting the changes, as does Michael Cullen in his memoir.

It's really only a narrative pushed by media that the reforms were bad for the country, and those journalists seem to think that it's a consensus view.

I guess we can only guess what NZ would have been like without reforms. My speculative opinion is it wouldn't have been great.

In my opinion reform was necessary - but it went too far.

They not only indexed benefits to consumer prices, Bolger and Shipley also removed the cost of land, the cost of existing houses, and the cost of servicing a mortgage from the CPI. This is why benefits now need to be topped up by accommodation and other supplements.

So it's no wonder inequality increased markedly as blue collar workers wage increases are generally tied to CPI (or less as one off payments in lieu of % increases were commonplace, and I even saw the Talleys use the wage index instead of the CPI, as it was lower) as are beneficiaries, and CPI never has represented the real cost of living since Bolger.

The poor and working class have really been hammered in the last 30 something years, and it is not their poor choices it was purely be design of governments who had always been a kind of benevolent, if slightly useless, dictatorship until after Muldoon.

So whether it was necessary or not, Bolger knows that it went too far and bordered on malevolence towards a sector of NZ society that has never recovered, and never will.

Rent is part of the CPI

I don't see where I said it wasn't Jimbo.

Yes rent is part of the basket, a paltry percentage, and new builds are as well, an even more paltry percentage.

The point is the weighting of housing in the CPI does not even get close to the cost for the average person.

And a lower CPI means lower interest rates which means higher house prices, which can go up and up and never affect the CPI enough for interest rates to bring house prices under control.

If that isn't malevolence by a government against people who don't own property, then what is.

“Hear, hear!”

"the weighting of housing in the CPI does not even get close to the cost for the average person" - surely that's the fault of Statistics NZ, not Rogernomics.

"the weighting of housing in the CPI does not even get close to the cost for the average person" - surely that's the fault of Statistics NZ, not Rogernomics.

Not correct. It's the fault of the 'dogma' that pervades the prevailing economic thought. Stats NZ are more or less do as they're told. They execute data collection and do not determine the constructs like CPI. Price inflation indexes across the Anglosphere are all designed in a manner that does not reflect the experiences of a representative citizen, particularly those to the left of the bell curve (and a good proportion of those 1 standard deviation to the right of the bell curve).

Trickle down economics only works when you have an innovative and productive population.

The alternative is everyone being equal (poor).

The only thing that trickles down is warm and yellow

The moment we use words, such as "Rogernomics" we virtually shut down intelligent conversation. Countries all over the world, including, particularly, Soviet bloc countries decided at roughly the same time that high levels of bureaucratic controls, even if introduced with good motives, were stultifying economic progress. This resulted in "new" thinking, perhaps the first since world reactions to the Great Depression. Each country lifted controls in a manner and speed depending on just how bad their particular economy was performing. NZ through the Labour government of David Lange decided, rightly or wrongly that reforms needed to happen quickly. I imagine that the architects (cabinet or bureaucrats) were quite surprised that by and large NZers took the changes sufficiently well that Labour was returned to power at the next election!

It is surely no surprise that both in the USSR and NZ, the first people "off the blocks" were the "wide boys" who used new freedoms to scoop up some cheap assets.

Again as in many countries, subsequent governments have reasserted some controls, albeit that in the main the horses had long bolted.

More important than raking over the tea leaves, we should all be concerned that the "fine tuning" of Bolger/Clark years will be seen as a need to reassert bureaucratic controls to the point we jump straight back into the poo!

I concede that NZ like Russia has it's old people who yearn for a return to the "good old days". But hopefully there might be some like me, who remember the grey hand of grey cardy wearing civil servants who not only said 'no' to most endeavours, but did so at huge cost to our economy.

Who will win...our plunging education standards and stalled productivity suggests we should all put our money on the grey cardies.

Agreed. Its a pity that more and more people seem to think neoliberal economics has failed us when really our economy is as strong as it has been in a long time. Our main issue is occurring in our most regulated market, doesn't that say it all?

Yes, the economy is strong, but Rogernomics brought with it the loss of a "mixed econonomy", and thus the resulting economy is strong for the top 1/3 and weak to poor for the bottom half. Pre Rogernomics New Zealand's "gray carddies mandate to say no was driven in the main by the fact that it was the Farmers practically single handily carrying the Export Economy on their back (international tourism was only a twinkle in the eyes of a few), and borrowing from abroad in the Billions for Consumer Spending and Trading Houses was not financially possible for the nation. Rogernomics not only ended agricultural subsidies and cutting provincial meat works etc jobs, but also doomed tens of thousands factory jobs throughout the country that produced Kiwi built consumer goods that kept most families happy-but not delighted. Delight is something that occurred post Rogernomics, but not for the majority, only for those in the right remaining job sectors. Same story goes for the US & UK, but in those nations the electorate rallied and in the last decade gave the ruling classes a shot across their bow. The people in the middle lost the last skirmish, but I doubt they have fired their last gun.

Jimbo

I think neo liberal economics has failed us... ( just as the promise of Keynesianism failed us ).

( Most good ideas, in the hands of politicians get corrupted... in my view )

Neo Liberalisms' most profound manifestation has been in the exponential growth of the FIRE economy.

(The GFC showed just what a false premise it was... ie deregulating the financial sector , on the basis the "private sector knows best ".)

Any apparent strength in our economy is mostly a function of the stimulus of debt...both Govt and private sector.

We have been a debtor nation for a long time.... running chronic current acct deficits.

This is called ... living beyond your means http://keithrankin.co.nz/chart/CurrentAccount.gif

In the long term.... unsustainable.... ( dependant on interest rates... I suppose )

Ray Dalio talks about Long term debt cycles...

Interesting to look at some of the unintended consequences of Rogernomics in regards to bureaucratic controls.

Mills suggests that Rogernomics intended to do away with bureaucratic controls.

In reality, with the concept of "user pays" , Rogernomics enabled the building of Bureaucratic "fiefdoms" ...

The Layers of high earning staff at Universities comes to mind.

I recall Civil Aviation charging a small aviation company $700 to change a mailing address...etc.

User pays gave these Govt agencies the ability to generate increasing incomes ...and grow..

Overall, looking back with the benefit of hindsight, my view is that Rogernomics was not the amazing thing I thought it might be.

With hindsight ...I see that Rogernomics was blinded by an ideology that said the private sector can always do things better than Govt.

As a young man during the 80s' I believed it....rogernomics..

I think over the yrs, my own reading and experience has shown me that some kind of Social market economy is probably the best compromise...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_market_economy#:~:text=The%20socia…(SOME,market%20and%20a%20welfare%20state.

Rogernomics might say a market economy knows best..

The Green party might say the key to getting rid of poverty is Distribution. ( A social economy)

A Social Market advocate might say production is just as important ( maybe more important) , than distribution...and sometimes it might be coordinated at a Govt level... A wealthy Nation is one whose people have a work ethic, are intelligent , creative and innovative....

And then using wisdom, we share the economic pie enuf so that most people can have a reasonable standard of living. ( Without becoming a "social welfare" state where we end up with intergenerational beneficiaries.)

Excellent points Roelof. I was mainly just suggesting that using words like Rogernomics or neoliberalism don't help much. But you are right, the ongoing effect of lifting stultifying controls on all manner of activities, plus a move to ensure private benefit government services were to be charged via user fees, plus changes to state sector legislation aimed at turning the "grey cardie" civil servants into dynamic, commercially astute business people, inevitably produced many unintended consequences.

One only needs to look at Auckland Council with over 3000 employees on plus $100k salaries, working in fiefdoms run by departmental Barons, each determined to meet budgets, in large measure using "user charges". A process otherwise called extortion. (I could give many examples)

To be a bit more balanced, even Roger D complained that his reforms were cut off prematurely when his boss got the " speed wobbles"! Heaven only knows the unintended consequences had he completed his mission!

All good stuff to look back, but don't we all hurtle forward into the future with our eyes firmly on the rearvision mirror? We are all human, even MP's. What we need to realise is that the TV series, "Yes Minister" wasn't a comedy...it was a documentary.

"NZ like Russia" - I see what you are doing there - very false equivalence.

As in Australia so in New Zealand, all neo-liberal.

We should thank the unemployed for their service. They've been used to control inflation

Governments have the power to lift hundreds of thousands of households out of poverty if they want to.

Those unemployed people have been assigned to Team Inflation Control without their knowledge. And for their patriotism, they've been ridiculed for being unemployed.

At the same time, successive governments have tightened the screws on unemployment benefits to "incentivise" those unemployed people to look for jobs in an economy where there haven't been enough jobs to go around by design.

To top it off, in the last two decades they've also been importing hundreds of thousands of workers from overseas, which has helped to suppress wages and weaken workers' bargaining power, as the Reserve Bank governor explained recently.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-04/the-unemployed-have-been-used-to…

Before-tax income and wage inequality also increased - it is not all about tax cuts for the rich and slashing benefits.

Popular narratives of the rise of income inequality in New Zealand frequently overlook the role that the state played as an employer of last resort. Many of the monopolies Brian alludes used those supernormal profits to provide jobs. Of course, providing jobs whether or not there was genuine work to be done resulted in these sectors being rather inefficient.

I would disagree with Brian on not gaining efficiencies and consumer benefits through Telecom being sold off.

I had friends at the time in financial services who would start work at 5am, call their clients and never hang up again. The sole reason for this was the complete lack of spare phone lines in the city at the time.

A customer focussed Telecom expanded services (for all that we slay them then and even now....) and enabled a land line to be installed quickly, not the multiple weeks of delays when it was a government service. In fact, we did better, and apparently so did the shareholders (of which I am not one). But we've ended up with a better service because of it as times changed faster than a government could have ever reacted - precisely the agility Easton references in his article.

Unlike in the UK, we corporatized prior to privatization, meaning that SOEs were given a clear objective - to make money for their shareholder (i.e. our government). As Richard Prebble likes to point out, this policy was highly effective. Most SOEs quickly returned a profit. Thus it is not improbable that we could have had the benefits of efficiency and market discipline without selling-off state assets. Those profits could then have been used to reduce tax burdens or fund public services.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.