By Jeongmin Seong and Jonathan Woetzel*

Asia is a technological force to be reckoned with. Over the last decade, the region has accounted for 52% of global growth in tech-company revenues, 43% of startup funding, 51% of spending on research and development, and 87% of patents filed, according to new research by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). How did Asia get here, and what lessons does its success hold for the rest of the world?

Of course, Asia is not a monolith, and technology gaps within the region remain significant. India, for example, has fewer large tech companies than other major economies. Still, four of the world’s top ten technology companies by market capitalisation are Asian.

China, home to 26% of the world’s unicorns (startups valued at $1 billion or more), leads the way in tech entrepreneurship in Asia, though it still relies on foreign inputs in core technologies. By contrast, advanced Asian economies like Japan and South Korea have large tech firms and a significant knowledge base, but relatively few unicorns. Asia’s emerging economies still invest relatively little in innovation, but they do provide growing markets for the goods and services produced by Asia’s tech leaders.

Against this background, Asian countries have had to make a virtue out of collaborating to overcome fragmentation and close technology gaps. And they have made considerable progress in recent years. Notably, they have invested heavily in regional tech startups – about 70% of such investment comes from within Asia – and robust regional technology supply chains.

While Asia’s technology supply chains continue to be reconfigured as they develop, the shifts have occurred largely within the region. (For example, the region’s developed economies and China have expanded investment in emerging economies’ manufacturing sectors.) This went a long way toward supporting Asia’s relative resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. The just-signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership could foster even closer intraregional ties.

Collaboration among countries is only part of the equation. Asian governments have also worked with local tech companies to advance goals in domains like renewable energy and artificial intelligence. During the pandemic, such partnerships have been essential to South Korea’s track-and-trace strategy, and to national health QR-code programs in China and Singapore. Asia is also developing new models for collaboration across digital ecosystems to help enterprises and societies share resources and information more effectively.

To be sure, Asian economies may find it difficult to catch up and compete in some well-established technology sectors – such as semiconductor design or operating system software – where others have a commanding market position. But there is no denying Asia’s tremendous progress in new technologies, often facilitated by its existing strengths in manufacturing and infrastructure.

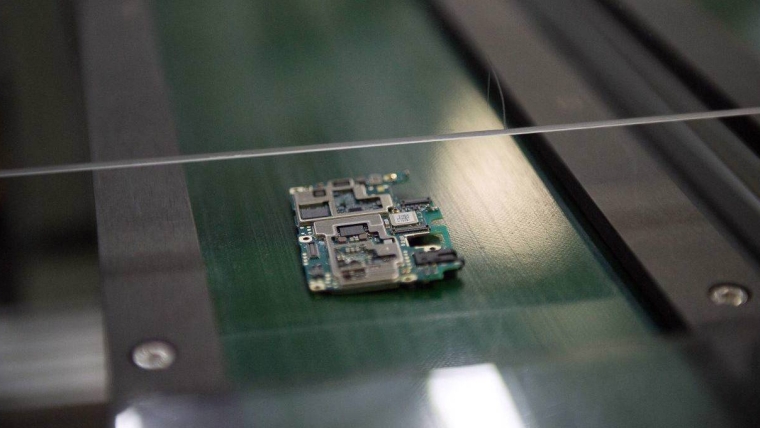

For example, more than 90% of the world’s smartphones are made in Asia. So, the region’s economies have focused significant innovative capacity in this area, such as to design mobile application processors and develop new types of hardware. Last year, the Chinese company Royole released the world’s first flexible smartphone. Early this year, Samsung went a step further, launching the first foldable smartphone with a foldable glass screen.

Similarly, Asian firms have capitalised on the region’s well-developed infrastructure to establish themselves at the cutting edge of 5G development and deployment. Of the five companies that hold the majority of 5G patents, four are Asian. Likewise, the region’s strong position in next-generation electric-vehicle batteries – more than half the world’s patents for solid-state batteries were filed in Asia – resulted from leveraging its existing strengths.

New opportunities are also opening up for Asia. While the region’s consumer markets are expanding and digitising rapidly, there is still a great deal of room for growth and innovation in consumer-facing technologies.

Similarly, Asia can expand its role in the growing market for digital information-technology services, such as big data and analytics, digital legacy modernisation, and “Internet of Things” system design. After all, the region has a huge pool of tech talent: India alone produced three-quarters of the world’s science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduates between 2016 and 2018.

Vulnerability to the effects of climate change, from deadly heatwaves to large-scale flooding, is also driving progress in the region. Asia already has the largest share of installed renewable capacity – 45% – compared to 25% in Europe and 16% in North America. The International Energy Agency expects that share to rise to 56% in 2040. With the support of investments in R&D and new infrastructure, Asia stands to make its mark on the world with technological solutions to climate risk.

Asia’s rapid development as a global technological leader over the last decade is a testament to the power of collaboration. And yet, in much of the world, the tide is turning toward isolationism and protectionism. Indeed, after years of relative openness, rising trade barriers threaten to disrupt global flows of technology and intellectual property.

This will sap potential in many frontier sectors. According to MGI’s simulation, $8-12 trillion of economic value could be at stake by 2040, depending on the quality and level of technology flows between China and the rest of the world. Many high-tech markets – including electric vehicles, battery storage, and advanced displays – depend on Asian investment and market growth to achieve global scale.

Asia is likely to continue to forge ahead with its technological development. But to make the most of its progress – and the strides that have been made elsewhere – enhancing technological collaboration within, and among regions, remains a priority for Asia and the rest of the world.

Jonathan Woetzel is a McKinsey senior partner and a director of the McKinsey Global Institute. Jeongmin Seong is a senior fellow at the McKinsey Global Institute in Shanghai. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019, published here with permission.

5 Comments

"After all, the region has a huge pool of tech talent: India alone produced three-quarters of the world’s science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduates between 2016 and 2018."

Wow that's 75% of total STEM graduates! But no mention of any technology innovation and achievement from the same country? Is the number correct?

It wouldn't surprise me. I work with many Indian IT contractors, one showed me a photo of his university graduation class from a few years ago. There were 250 in the photo, and that was for class on one day. Actual quality of graduates is...highly variable, but then that's true of any graduating class from any nation.

I suspect China has made much larger strides in tech innovation than India due to the former's more liberal approach to the concept of IP.

NZ is on the right path, as we speak the STEM for second largest ethnicity population (Maori) and fourth largest ethnicity population (Pasifica) have been boosted nationwide, in every sectors to unprecedented level.. never be seen in 150yrs of NZ history. Higher education seats, graduation, govt job placement etc. The first largest ethnicity (Pakeha) providing the clear policy and the third largest ethnicity (Asians, ASEAN) will provide taxable essential workers contribution to smooth the pathway.. Nice. The third largest must accept that condition as part of the deal to settle in NZ, yea.. Nice. Soon NZ, will announce the first world class higher learning institution that focusing in 'multi trillion dollar' gaming business, we provide the supply of trained players for worldwide prized competition, cadet mentoring, coding class for gaming, NZ gaming STEM will lead the world on how to cleverly navigate the 24hrs of human daily lives; 8hrs taken for sleep/rest, the remaining 16hr short windows is for family time, shopping/cooking/get ready, working/study, traveling/traffic and for sure hours of playing 'perfecting the games skill'

Do you really mean it or simply sarcasm?

Sony, Samsung, Lenovo, Alibaba... the list goes on. There are also successful ICT businesses founded by Asian entrepreneurs in the West, such as Infosys, Zoom and Gentrak. Asia has been the digital powerhouse for some time. It is the result of education, mentality, leadership and scale and economy.

If NZ wants to take the lead (or realistically, to catch up) in this space, then it needs to accept and promote more thoughtful Asian leaders.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.