By Yi Fuxian*

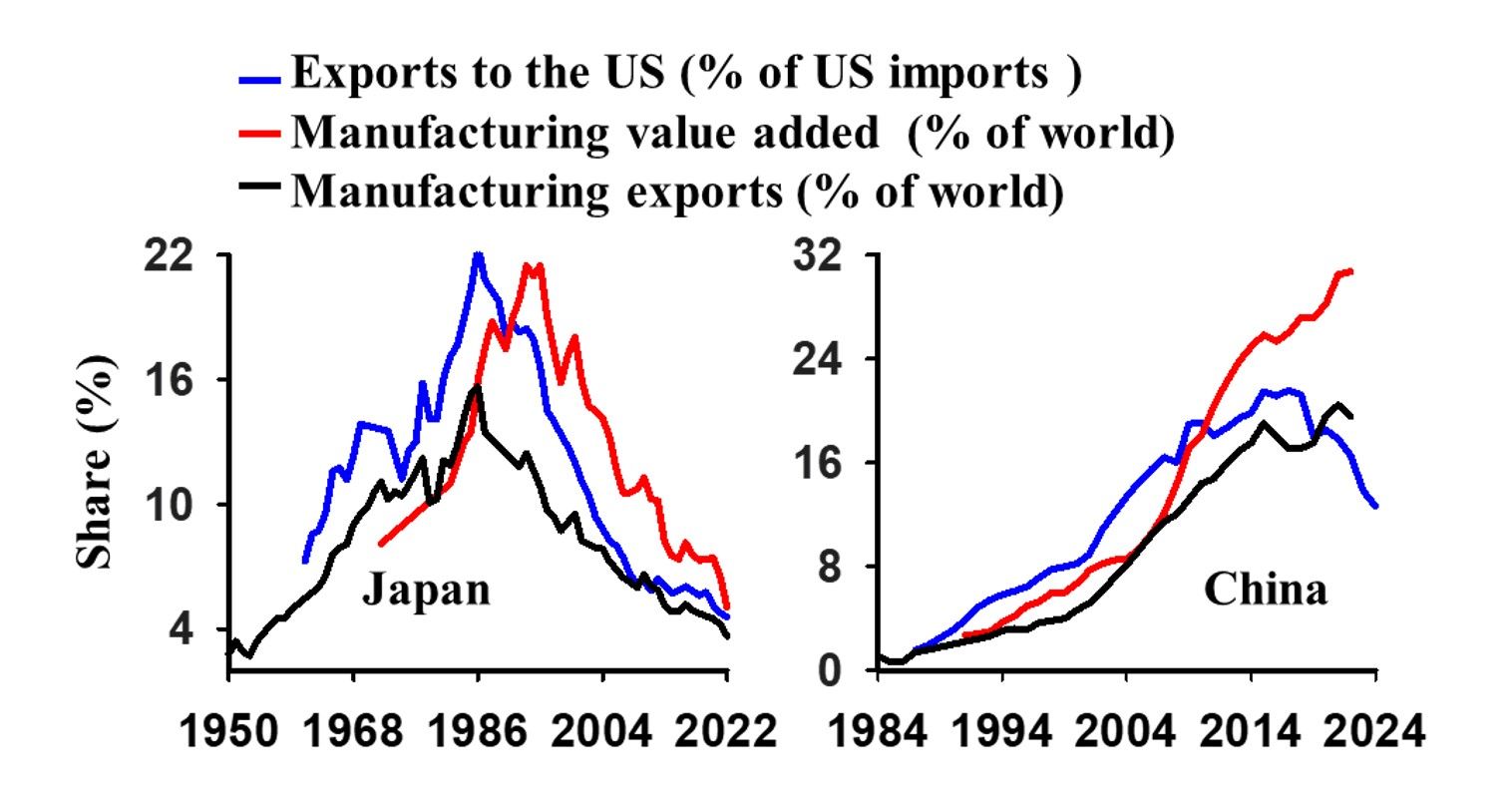

Chinese overcapacity is raising concerns worldwide. It is easy to see why: China accounts for nearly one-third of the world’s manufacturing value-added, and one-fifth of global manufacturing exports. But there is good reason to believe that the decline of China’s manufacturing sector is imminent.

To understand what is happening now in China, it is worth recalling Japan’s recent history. After World War II, Japan’s manufacturing sector grew rapidly, thanks largely to access to the massive US market. But the 1985 Plaza Accord (which boosted the yen’s value and weakened Japanese exports), together with an ageing population and a shrinking labour force, reversed this trend.

From 1985 to 2022, the share of Japanese goods in US imports dropped from 22% to 5%, and Japan’s share of global manufacturing exports declined from 16% to 4%. Moreover, Japan’s share of global manufacturing value-added fell sharply, from 22% in 1992 to 5% in 2022. And the number of Japanese companies on the Fortune Global 500 list dropped from 149 in 1995 to just 40 today.

As the chart shows, China has followed a similar upward trajectory in recent decades, but China’s manufacturing rise was even more dependent on the US market. Japan’s imports from the United States equaled 51% of its exports to the US in 1978-84, compared to a 23% share for China in 2001-18.

Chinese family-planning policies are largely to blame for this imbalance. Typically, household disposable income would account for 60% to 70% of a country’s GDP, in order to sustain household consumption of around 60% of GDP. In China, however, the one-child policy – which was in place from 1980 until 2015 – limited household earnings, encouraged high savings, and constrained domestic demand.

As a result, Chinese household disposable income dropped from 62% of GDP in 1983 to 44% of GDP today, with household consumption falling from 53% of GDP to 37% of GDP. In Japan, by contrast, household consumption equals 56% of GDP. One can look at it this way: if wages would normally amount to US$60-70, Chinese workers receive only US$44 and have just US$37 of spending power, whereas Japanese workers have US$56 of spending power.

China’s government, however, has plenty of financial resources, which it uses to support industrial subsidies and investment in manufacturing. Moreover, because China’s manufacturing sector offers high returns, international investors are willing to channel capital toward it. Add to that a surplus of about 100 million workers, and excess capacity is difficult to avoid.

Given insufficient demand at home, China’s only option for reducing its excess capacity and creating enough jobs for its population is to maintain a large current-account surplus. That is where the US comes in: the share of Chinese goods in US imports rose from 1% in 1985 to 22% in 2017. In 2001-18, the US accounted for three-quarters of China’s trade surplus.

China’s giant surplus is the mirror image of America’s deficit, and while the rise of Chinese manufacturing is hardly the only reason for the decline of US manufacturing, it is a big one. America’s share of world manufacturing exports remained stable, at 13%, between 1971 and 2000, but fell sharply after China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, and stood at just 6% in 2022. America’s share of manufacturing value-added likewise plummeted, from 25% in 2000 to 16% in 2021.

As these trends decimated America’s Rust Belt, which stretches from Wisconsin to eastern Pennsylvania, popular frustration with globalisation, and with the “political elites” who had encouraged it, grew steadily. In 2016, Donald Trump rode their frustration into the White House, vowing to revive US manufacturing and force China to change its trading practices. And Trump hopes to do the same this November.

In this sense, China’s one-child policy indirectly but profoundly reshaped the American political landscape. And now American politics are reshaping China’s economy. The US backlash against China, which began with Trump’s tariffs in 2018 and has intensified under President Joe Biden, has caused the share of Chinese goods in US imports to drop to just 12.7% in the first half of 2024.

Beyond losing the American market, China is losing some of its own manufacturing companies, which are shifting part of their production to countries such as Vietnam and Mexico, to avoid US tariffs. This partial transfer augurs a wider withdrawal, much like that faced by Japan’s manufacturing sector as it fell into decline.

China is looking increasingly like Japan for two other reasons. First, its workforce is rapidly shrinking and ageing. According to the government, annual births have plummeted from 23.4 million, on average, in 1962-90 to just nine million last year, and even that figure is probably grossly exaggerated. Within a few years, China will probably record just six million births per year. Meanwhile, the median age of migrant workers, who make up 80% of China’s manufacturing workforce, has risen from 34 in 2008 to 43 last year, with the share of people over 50 rising from 11% to 31%. Some manufacturing plants are already closing for lack of workers.

Second, China’s services sector is set to squeeze manufacturing. As China’s government seeks to increase the GDP share of household disposable income, Chinese demand for US goods will rise, and some manufacturing workers will shift to services, which is also where China’s rapidly growing pool of college graduates will find employment.

The decline of manufacturing might not happen as fast as it did in Japan, because China has a larger domestic market and a more complete industrial ecosystem, and because it is investing heavily in artificial intelligence and robotics, which could deliver productivity gains. But decline is both inevitable and irreversible. Unfortunately for the US, however, this will not necessarily bring about a revival of domestic manufacturing.

*Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, spear-headed the movement against China’s one-child policy and is the author of Big Country with an Empty Nest. Copyright 2024 Project Syndicate, here with permission.

21 Comments

While technological effects are notoriously hard to predict, there have been a couple of substantial changes since Japan's rise as a manufacturing power, that may have an impact. I'm not going to make predictions, but I do wonder about what's going to happen in these areas -

The effects of additive and other new manufacturing technologies are still to really be felt. It may facilitate a re-localisation of manufacturing physical goods to market countries (problematic for China), or maybe the rise of genuine customisation by expert manufacturers - who just might be located in China as the manufacturing concerns there are not scared of spending money on productivity equipment.

And the impact of AI automation on a workforce? There might be a lot of reluctance in the Western Democracies to make entire workforces essentially redundant, but what would be the effect in a centrally planned economy like China - would that lead to equal or greater reluctance, given the demographic pressures?

In the field I have expertise in the west still manufactures the critical and technical items for industry.And supplements that production with lower cost consumer products made in the east, primarily china.

At first I was annoyed that you didn't use a capital letter for "the west", then I saw you did the same for "the east" and even for "china". Believe it or not, according to Fowler, there are no strict rules except that one should be consistent, which you are.

Interesting article. Next few years will be interesting - esp with who replaces Xi.

I think Lai Ching-te would be an excellent successor to President Xi ...

Han Kuo-yu and Ko Wen-je are definitely top contenders to succeed Chairman Xi! Han is still the certified Saviour of China, while Ko has a resume that's hard to beat: he bussed to work, could cycle from Taipei to Kaohsiung in a single day, and boasts an IQ of 157. And let’s not forget Ko’s unmatched generosity—he gave away benefits to financial tycoons, free of charge! (except the recipients are now remanded in custody). If these aren't leadership material, I don't know what is!

Right, so the chinese emperor will be replaced with the jailed leader of a Taiwanese party. Is that before or after Taiwan invades and annexes the mainland?

Ko Wen-je arrest plunges Taiwan's No. 3 party into crisis of trust

What makes you think Xi will be replaced in the next few years?

Who will be the first big name to production to Africa? Will only take one and the floodgates will open.

China has established a few manufacturing plants in Africa. Not sure how it is going. I believe the jury is still out although there are some positive reports for the locals. Africa is an enormous place with around 54 distinct countries. The Chinese have had to build considerable infrastructure, financed by loans, which has led to accusations of debt trapping.

Chinese family-planning policies are largely to blame for this imbalance.

While the one child policy was not a great move, Chinas birth rate has mirrored that of other East Asian nations as they develop and urbanise. Japan and Koreas birth rates are lower, and that happened without the government legislating against larger families.

One other factor for China that Japan didnt have the advantage of, is half a billion people still living rurally.

But overall, they'll probably go the way of Japan. Maybe just slower.

. . I'll wager you the opposite : that China's population collapses by nearly a half by year 2100 ... a far more precipitous fall than that of Japan ...

China is looking increasingly like Japan for two other reasons. First, its workforce is rapidly shrinking and ageing. According to the government, annual births have plummeted from 23.4 million, on average, in 1962-90 to just nine million last year, and even that figure is probably grossly exaggerated. Within a few years, China will probably record just six million births per year.

How long can they stagger on without accepting immigration? Japan hasn't really yet but they are a much more prosperous country.

Neither will be very successful at securing a lot of migrants.

They will if they introduce a welfare state.

Germany has a welfare state, is pretty wealthy, and struggles to attract migrants.

Japan and China are even less accessible as a destination for migrants.

The English language makes countries more accessible.

Language and culture. It's harder to assimilate into a monoculture.

Germany has had a familiar challenge when looking to attract talent. Plenty of business/commerce/social science majors flocking into the country from all over the world creating an oversupply. However, not enough skilled tradies, engineers, technicians, etc.

Blue-collared occupations are still unorganised in most developing countries with high emigration rates (India, Bangladesh, etc.) in the sense that they don't have formal training and non-native language skills that allows global mobility.

There's still a lot of people that want to live in Japan. For low level jobs this will continue to be Vietnam and increasingly Indonesia for Japan (agricultural type positions is where they fill gaps). Japan hit over 2m foreign workers this year.

The same applies to Korea. Vietnam and the Philippines and Indonesia could continue to fill gaps at the lower end.

I'd argue Vietnam and Korea are similar enough culturally that integration is possible (despite, umm, the koreans being puppets of the americans in the 70s) and the Koreans have invested heavily in Vietnam manufacturing the last couple of decades that could pull through skilled migration at some point (rather than rural farm wifes).

China will never have the same pop culture pull as Japan and Korea, and it is very dominant in South Asia. Much as much of the world glamarised America growing up the same happens now with Korea in ASEAN (until they visit and realise this ain't going to be a Cinderella story).

This analysis kind of overlooks what Japan did in the 80s. In effect, they went on a global shopping spree buying up productive assets all over the world. And these assets continue to return money to Japan. China will be no different.

Case in point: Anyone tried any of NZ's great whiskies? No? You need to go to Japan and other places to sample them. Japan bought them all in the 80s.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.