The paper opened an entire research field. Since then, more than 7000 published studies have shown the prevalence of microplastics in the environment, in wildlife and in the human body.

So what have we learned? In a new paper, an international group of experts, including myself, summarise the current state of knowledge.

In short, microplastics are widespread, accumulating in the remotest parts of our planet. There is evidence of their toxic effects at every level of biological organisation, from tiny insects at the bottom of the food chain to apex predators.

Microplastics are pervasive in food and drink and have been detected throughout the human body. Evidence of their harmful effects is emerging.

The scientific evidence is now more than sufficient: collective global action is urgently needed to tackle microplastics – and the problem has never been more pressing.

Microplastic pollution is the result of human actions and decisions. We created the problem – and now we must create the solution.

Tiny particles, huge problem

Microplastics are generally accepted as plastic particles 5mm or less in one dimension.

Some microplastics are intentionally added to products, such as microbeads in facial soaps.

Others are produced unintentionally when bigger plastic items break down – for example, fibres released when you wash a polyester fleece jacket.

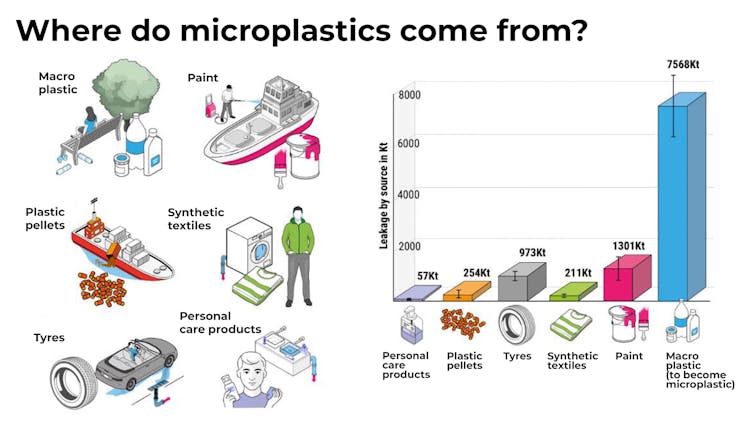

Studies have identified some of the main sources of microplastics as:

- cosmetic cleansers

- synthetic textiles

- vehicle tyres

- plastic-coated fertilisers

- plastic film used as mulch in agriculture

- fishing rope and netting

- “crumb rubber infill” used in artificial turf

- plastics recycling.

Science hasn’t yet determined the rate at which larger plastics break down into microplastics. They are also still researching how quickly microplastics become “nanoplastics” – even smaller particles invisible to the eye.

Measuring the microplastic scourge

It’s difficult to assess the volume of microplastics in the air, soil and water. But researchers have attempted it.

For example, a 2020 study estimated between 0.8 and three million tonnes of microplastics enter Earth’s oceans in a year.

And a recent report suggests leakage into the environment on land could be three to ten times greater than that to oceans. If correct, it means between ten and 40 million tonnes in total.

The news gets worse. By 2040, microplastic releases to the environment could more than double. Even if humans stopped the flow of microplastics into the environment, the breakdown of bigger plastics would continue.

Microplastics have been detected in more than 1300 animal species, including fish, mammals, birds and insects.

Some animals mistake the particles for food and ingest it, leading to harm such as blocked intestines. Animals are also harmed when the plastics inside them release the chemicals they contain – or those hitch-hiking on them.

Microplastics in the environment could more than double by 2040. Shutterstock.

Invaders in our bodies

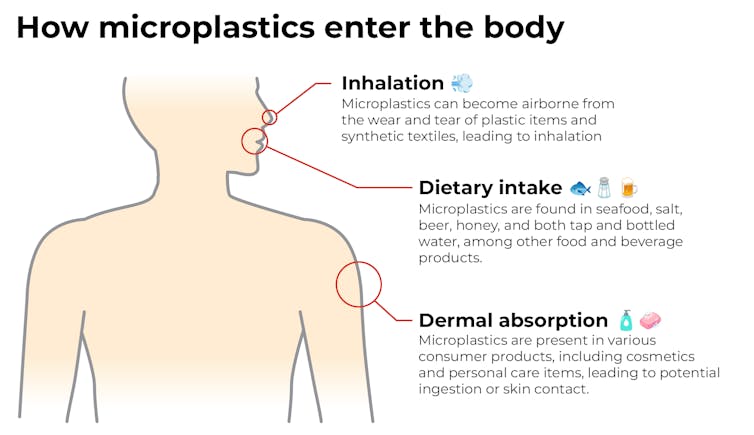

Microplastics have been identified in the water we drink, the air we breathe and the food we eat – including seafood, table salt, honey, sugar, beer and tea.

Sometimes the contamination occurs in the environment. Other times it’s the result of food processing, packaging and handling.

More data is needed on microplastics in human foods such as land-animal products, cereals, grains, fruits, vegetables, beverages, spices, and oils and fats.

The concentrations of microplastics in foods vary widely – which means exposure levels in humans around the world also varies. However, some estimates, such as humans ingesting a credit card’s worth of plastic every week, are gross overstatements.

As equipment has advanced, scientists have identified smaller particles. They’ve found microplastics in our lungs, livers, kidneys, blood and reproductive organs. Microplastics have crossed protective barriers into our brains and hearts.

While we eliminate some microplastics through urine, faeces and our lungs, many persist in our bodies for a long time.

So what effect does this have on the health of humans and other organisms? Over the years, scientists have changed the way they measure this.

They initially used high doses of microplastics in laboratory tests. Now they use a more realistic dose that better represents what we and other creatures are actually exposed to.

And the nature of microplastics differ. For example, they contain different chemicals and interact differently with liquids or sunlight. And species of organisms, including humans, themselves vary between individuals.

This complicates scientists’ ability to conclusively link microplastics exposure with effects.

In regards to humans, progress is being made. In coming years, expect greater clarity about effects on our bodies such as:

- inflammation

- oxidative stress (an imbalance of free radicals and antioxidants that damages cells)

- immune responses

- genotoxicity – damage to the genetic information in a cell that causes mutations, which can lead to cancer.

What can we do?

Public concern about microplastics is growing. This is compounded by our likely long-term exposure, given microplastics are almost impossible to remove from the environment.

Some countries have implemented laws regulating microplastics. But this is insufficient to address the challenge. That’s where a new legally binding agreement, the UN’s Global Plastics Treaty, offers an important opportunity. The fifth round of negotiations begins in November.

The treaty aims to reduce global production of plastics. But the deal must also include measures to reduce microplastics specifically.

Ultimately, plastics must be redesigned to prevent microplastics being released. And individuals and communities must be brought on board, to drive support for government policies.

After 20 years of microplastics research, there is more work to be done. But we have more than enough evidence to act now.![]()

*Karen Raubenheimer, Senior Lecturer, University of Wollongong.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.