By Victor Counted, Byron R. Johnson & Tyler J. VanderWeele*

What does it mean to live a good life? For centuries, philosophers, scientists and people of different cultures have tried to answer this question. Each tradition has a different take, but all agree: The good life is more than just feeling good − it’s about becoming whole.

More recently, researchers have focused on the idea of flourishing, not simply as happiness or success, but as a multidimensional state of well-being that involves positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment − an idea that traces back to Aristotle’s concept of “eudaimonia” but has been redefined within the well-being science literature.

Flourishing is not just well-being and how you feel on the inside. It’s about your whole life being good, including the people around you and where you live. Things such as your home, your neighborhood, your school or workplace, and your friends all matter.

We are a group of psychological scientists, social scientists and epidemiologists who are all contributors to an international collaboration called the Global Flourishing Study. The goal of the project is simple: to find patterns of human flourishing across cultures.

Do people in some countries thrive more than others? What makes the biggest difference in a person’s well-being? Are there things people can do to improve their own lives? Understanding these trends over time can help shape policies and programs that improve global human flourishing.

What does the flourishing study focus on?

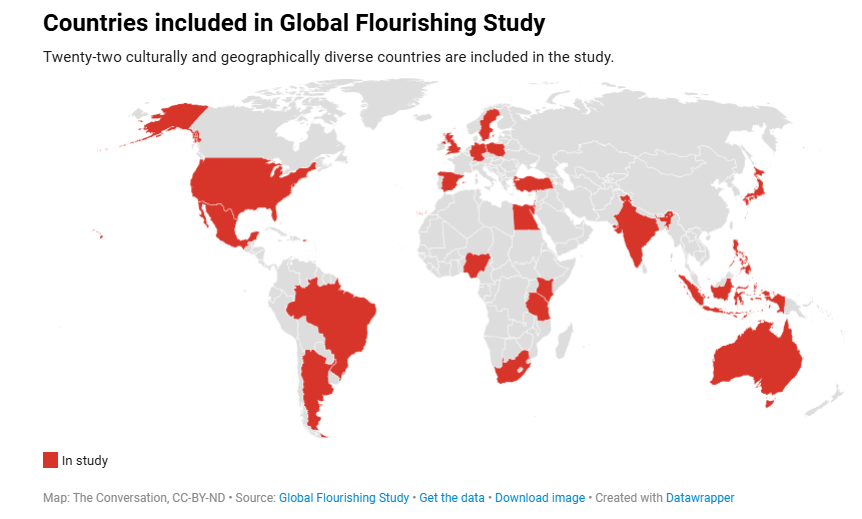

The Global Flourishing Study is a five-year annual survey of over 200,000 participants from 22 countries, using nationally representative sampling to understand health and well-being. Our team includes more than 40 researchers across different disciplines, cultures and institutions.

With help from Gallup Inc., we asked people about their lives, their happiness, their health, their childhood experiences, and how they feel about their financial situation.

The study looks at six dimensions of a flourishing life:

-

Happiness and life satisfaction: how content and fulfilled people feel with their lives.

-

Physical and mental health: how healthy people feel, in both body and mind.

-

Meaning and purpose: whether people feel their lives are significant and moving in a clear direction.

-

Character and virtue: how people act to promote good, even in tough situations.

-

Close social relationships: how satisfied people are with their friendships and family ties.

-

Financial and material stability: whether people feel secure about their basic needs, including food, housing and money.

We tried to quantify how participants are doing on each of these dimensions using a scale from 0 to 10. In addition to using the Secure Flourish measure from Harvard’s Human Flourishing Program, we included additional questions to probe other factors that influence how much someone is flourishing.

For example, we assessed well-being through questions about optimism, peace and balance in life. We measured health by asking about pain, depression and exercise. We measured relationships through questions about trust, loneliness and support.

Who is flourishing and why?

Our first wave of results reveals that some countries and groups of people are doing better than others.

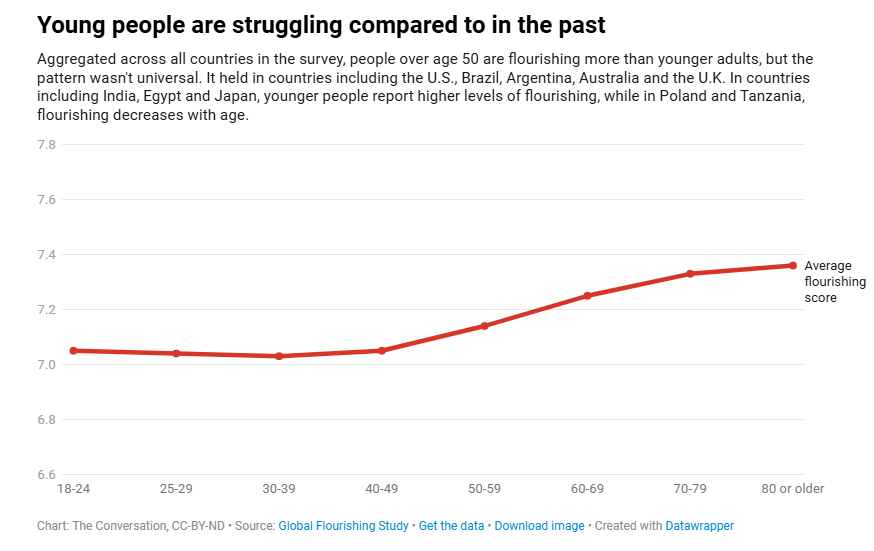

We were surprised that in many countries young people are not doing as well as older adults. Earlier studies had suggested well-being follows a U-shape over the course of a lifespan, with the lowest point in middle age. Our new results imply that younger adults today face growing mental health challenges, financial insecurity and a loss of meaning that are disrupting the traditional U-shaped curve of well-being.

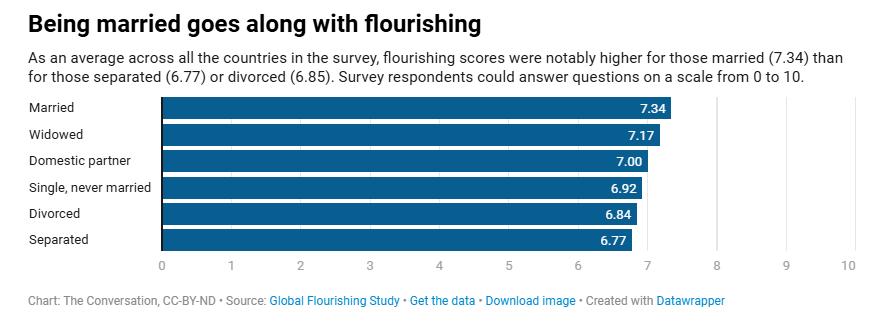

Married people usually reported more support, better relationships and more meaning in life.

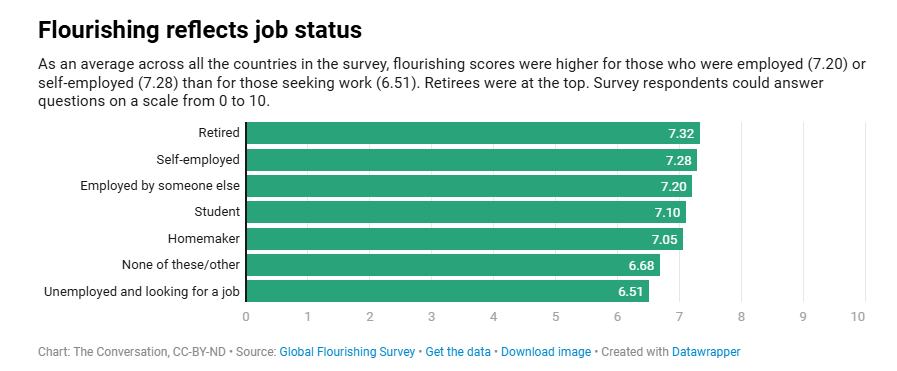

People who were working – either for themselves or someone else – also tended to feel more secure and happy than people who were seeking jobs.

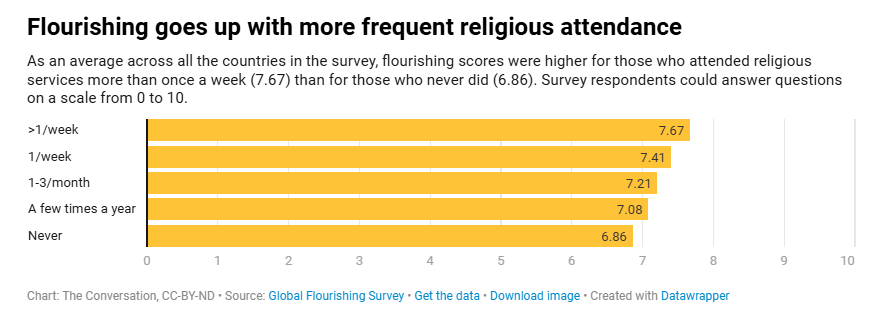

People who go to religious services once a week or more typically reported higher scores in all areas of flourishing – particularly happiness, meaning and relationships. This finding was true in almost every country, even very secular ones such as Sweden.

It seems that religious communities offer what psychologists of religion call the four B’s: belonging, in the form of social support; bonding, in the form of spiritual connection; behaving, in the cultivation of character and virtue through the practices and norms taught within religious communities; and believing, in the form of embracing hope, forgiveness and shared spiritual convictions.

But some people who attend religious services also report more pain or suffering. This correlation may be because religious communities often provide support during hard times, and frequent attendees may be more attentive to or more likely to experience pain, grief or illness.

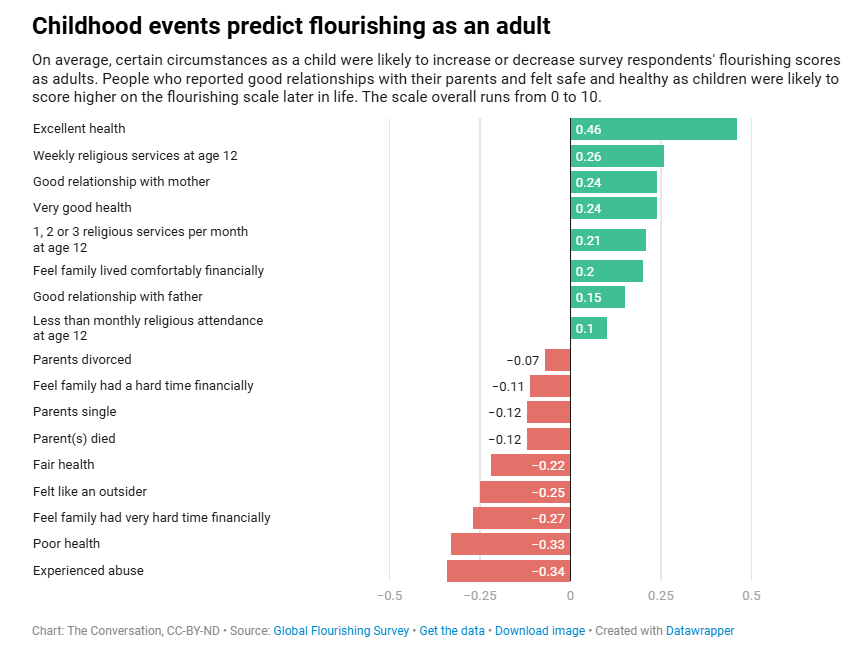

Your early years shape how you do later in life. But even if life started off as challenging, it doesn’t have to stay that way. Some people who had difficult childhoods, having experienced abuse or poverty, still found meaning and purpose later as adults. In some countries, including the U.S. and Argentina, hardship in childhood seemed to build resilience and purpose in adulthood.

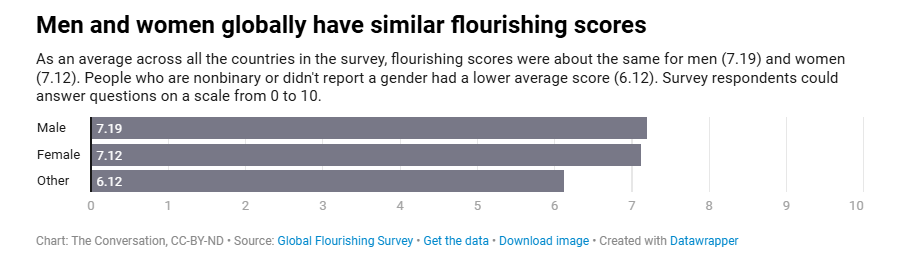

Globally, men and women report similar levels of flourishing. But in some countries there are big differences. For example, women in Japan report higher scores than men, while in Brazil, men report doing better than women.

Where are people flourishing most?

Some countries are doing better than others when it comes to flourishing.

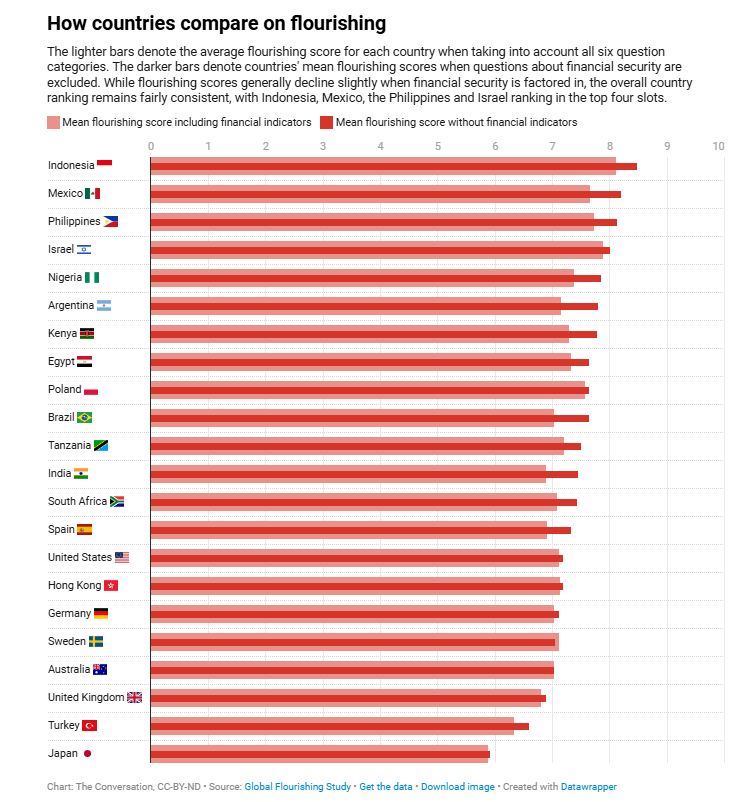

Indonesia is thriving. People there scored high in many areas, including meaning, purpose, relationships and character. Indonesia is one of the highest-scoring countries in most of the indicators in the whole study.

Mexico and the Philippines also show strong results. Even though these countries have less money than some others, people report strong family ties, spiritual lives and community support.

Japan and Turkey report lower scores. Japan has a strong economy, but people there report lower happiness and weaker social connections. Long work hours and stress may be part of the reason. In Turkey, political and financial challenges may be hurting people’s sense of trust and security.

One surprising result is that richer countries, including the United States and Sweden, are not flourishing as well as some others. They do well on financial stability but score lower in meaning and relationships. Having more money doesn’t always mean people are doing better in life.

In fact, countries with higher income often report lower levels of meaning and purpose. Meanwhile, countries with higher fertility rates often report more meaning in life. These findings show that there can be a trade-off. Economic progress might improve some things but weaken others.

The big picture

The Global Flourishing Study is helping us see that people all over the world want many of the same basic things: to be happy, healthy, connected and safe. But different countries reach those goals in different ways. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to flourishing. What it means to flourish can look different from place to place and from one person to another.

One challenge with the Global Flourishing Study is that it uses the same set of questions in all 22 countries. This method, known as an etic approach, helps us compare results across cultures. But it can miss the nuance and local meanings of flourishing. What brings happiness or purpose in one country or context might not mean the same thing in another.

We consider this study to be a starting point. It opens the door for more emic studies – research that uses questions and ideas that fit the values, language and everyday life of specific cultures and societies. Researchers can build on this study’s findings to expand how we understand and measure flourishing around the world.![]()

*Victor Counted, Associate Professor of Psychology, Regent University; Byron R. Johnson, Distinguished Professor of the Social Sciences and Director of the Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University, and Tyler J. VanderWeele, Professor of Epidemiology, Harvard University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

18 Comments

It was revelatory in my younger years seeing happier people in much poorer parts of the world than I was experienced to in my own country.

I'd have to say the happiest sort of living environment is semi-rural agrarian communities, where food production is reasonably reliable. Not based on many metrics other than the amount of smiling and person to person interactions witnessed.

Doesn't seem that complicated, people thrive better when there's some sort of decent shared culture and close kinship with family and the wider community. In the West, we try to fill our lives with stuff, all sectioned off into our postage stamp sized living spaces, competing with one another for resources and status, with no guiding principles other than our own individual interests.

And we only seem to be making it worse.

Agreed.

We will revert to local, and community (which means max 150ish) and largely food-production-orientated. It is a pleasant way of life (40= years of experience backing that claim).

It feels a little odd that the word 'education' doesn't appear in the article.

Not that it makes you flourish per se, but as a means to an end.

Or opportunity. Or social mobility.

It's not been that effective at either in more recent years. We just made quals necessary for work that previously didn't need it.

means to an end, opportunity, social mobility....

Key catch phrases to perpetuate the notion of growth measured in gdp stats - the God of mammon. Arguably the repressor of flourishing.

Painter shares similar insights to my own experiences of monetarily poor societies.

I reflect on my 70 years (well the last 50 or so) and conclude there has been an unrelenting pursuit of commodification to extract $ profit from almost all aspects of our lives in NZ (an advanced developed nation), penetrating right down to the fundamental foundations of child raising (disguised in the misleading title of early childhood education). ECE enables both parents or the sole parent to work - grist to the mill of economic growth.

It is no surprise to me that Indonesia sits at the top of the table. If Western deveoped nations had their way though, they'd soon drag it down into the pack with us by 'development' to convert their millions of citizens away from their traditional societal structures and into self seeking consumerism and materialism that typifies we 'developed' societies.

If we look at how many Indonesians live, outside of the cities you have multiple generations living in one compound. Often in individual houses, but then with shared common areas where everyone eats and hangs out.

- no ECE (grandparents are looking after kids while parents work)

- shared resources among everyone (whereas each house in our society has to have its own washing machines, cooking appliances, etc)

- retirement villages aren't a thing (family looks after it's elderly)

- property ownership is generational

- kids get to be raised by more than 1 or 2 adults

- there's a support network of multiple people, and more socialisation

We basically worked out in our society a way for everyone to be poorer, and lonelier.

My experience is in Timor-Leste. Same same.

There are certainly areas in the 'Development' complex that are commodified. To a large degree, the international NGOs exist from project to project, putting significant resource into designing the next project to continue there existence. But often developed through a western developed nation lens whereby the western social and economic systems = the best to aspire to, and traditional in-country social and economic systems = bad

It's rather illuminating that that's where your thought process took you, when I made no such comments or inferences about economics, finance or even money.

A good education - as opposed to box-ticking training - helps to understand and interpret the world, and is an unexamined life worth living?

Social mobility and opportunity allow change in the status of the self. Look at how poorly informal-but-rigid social structures were the enemy of talent and merit in England.

The inference I took from the article was that flourishing lies, at least in part, in contentment with station in life, which was at the heart of Christian doctrine, and it underpins fatalism, rigid social order, and difficulties in adaptation to new circumstances.

It's rather illuminating that that's where your thought process took you, when I made no such comments or inferences about economics, finance or even money.

I thought that what you were inferring with opportunity and social mobility. Social mobility being inherently tied to income/wealth.

A good education - as opposed to box-ticking training - helps to understand and interpret the world, and is an unexamined life worth living?

Any life can be worth living. Some schools of thought would consider examination to be over rated, and actually a hindrance to living as a fully integrated human.

We have philosophies and religions, ultimately these are at best maps to a way of being that is beyond words, and even beyond thought. It can be accessed as easily by an illiterate peasant in a field as it can by our champions of academia.

I've gleamed about as much wisdom making compost as I have sitting in a lecture theatre.

Agree again - I took Golem's comment as disparaging. But he has a point re the retention of raw knowledge - theoretically that costs nothing, and at any existence level from here on in, knowing the science of what you are doing, will be useful.

So too cultural knowledge - history, geography, philosophy - will be useful.

But you are dead right - and Lou B is even righter; education has been commodified, as has everything not bolted down. That trend has maxed out, and we need to re-claim the Commons - what's left of it.

But you are dead right - and Lou B is even righter; education has been commodified, as has everything not bolted down. That trend has maxed out, and we need to re-claim the Commons - what's left of it.

This, and social media, IMO are the sole reasons for disparaged youth currently. You used to be able to easily move out of home at 18, find a job and work your way up. Pay as you go, with relatively fixed timelines e.g paying down a mortgage. Today the youth grow being attacked on all fronts - everything trying to suck them dry - be it attention, money, or opportunity. When comparing themselves yo their parents and grandparents, it isn't surprising they feel hard done by, but then again the world is slowly eating away their social skills which are sorely needed to coordinate and succeed.

It's an interesting study, but I think a bit wrong-headed from a philosophical point-of-view.

For Aristotle, eudaimonia is the highest human good, the only human good that is desirable for its own sake (as an end in itself) rather than for the sake of something else (as a means toward some other end).

Like level of dedication to healing the sick; or pleasure derived from observing a butterfly (appreciation of the wonders of nature); or level of devotion to a parent in their old age; or exhaustively working in the service of the natural environment on a voluntary basis.

Eudaimonia has to be thought of in the terms of morality - the moral virtues. Not to be confused with religion/religious dogma. It is more a state of spiritual contentment - a happy soul. A modern expression that reflects eudaimonia to me is, an "old soul" or "salt of the earth". Yes, hard to measure within a whole population and make 'grouped' assumptions.

So, it seems the criteria chosen by the study authors weighed more in the direction of happiness - a completely different concept in Aristotelean ethics;

https://www.britannica.com/topic/eudaimonia

As they sorta hinted, it's quite hard to compare this across a range of cultures.

In the West, we've largely commodified happiness, as something you get at the end of an anticipatory chain, whether it's acquisition of a good or a life milestone. I'll get this Mercedes, then I'll be happy, or I'll retire, then be happy.

This makes happiness somewhat fleeting, and something to be sought, rather than something that can be uncovered, if we get out of our own way.

A problem solved, thousands of years ago

Interesting take. I see it as happiness has been held up on too higher pedestal. Happiness is an emotion which will come and go as emotions do, however fulfilment and contribution should be held in higher regard.

Social media has bought the problems of the world into your pocket, I think its been net negative, especially for those who never grow up without it, thus no balance.

Even for the elders, seems like everyone's got adult ADHD now

So, you're context switching every 5 seconds on a glass screen, and now find it hard to focus?

No kidding

Indonesia has a long way to go. Corruption and malnutrition is flourishing. Though I guess when the study looked at how "how healthy people feel", rather than how healthy they actually are, you are going to get skewed results.

"Data from the 2023 Indonesian Health Survey (SKI) recorded stunting prevalence in toddlers at 21.5 percent; underweight, 15.9 percent; wasting, 8.5 percent; and obesity, 4.2 percent. This condition is experienced not only by toddlers but also by school-aged children.

...People tend to consume less diverse and nutritionally balanced food. The results of the 2023 SKI showed less consumption of vegetables in 86.7 percent of people aged five years and above. In fact, 11.8 percent have never consumed vegetables.

Apart from vegetable consumption, animal protein intake is also still lacking in Indonesia."

https://en.antaranews.com/news/327851/tackling-malnutrition-in-indonesi…

Though I guess when the study looked at how "how healthy people feel", rather than how healthy they actually are, you are going to get skewed results.

That's not what the study is measuring or asking. Health is only one component of what's deemed to be overall human wellbeing.

Our society has focused on the sorts of raw data you are prioritizing. Which are desirable in a purely objective sense, but clearly not the be all and end all in living a good life.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.