Last week, in a series of interviews with the press, notably with Newstalk ZB, Finance Minister Nicola Willis dropped several hints about what might be in the forthcoming May 22nd Budget. In particular, she talked about the corporate tax rate, and the possibility of cuts to that as part of promoting the Government's growth agenda.

Corporate tax rate above OECD average

Speaking with Heather Du Plessis-Allan, Ms Willis commented:

“Well, if you compare New Zealand with the rest of the world, we're not as competitive as we used to be. Which is to say that our corporate tax level is reasonably high when you compare it to the rest of the developed world.”

This is a very valid point which comes up frequently in discussions. Our current company tax rate at 28% well above the OECD average of 24% and has been out of alignment for some time.

New Zealand back in the late 80s under the Fourth Labour Government was actually at the forefront of cutting company tax rates. A particularly interesting action was to align the company tax rate with the top individual and trust rates of 33%. The three basically stayed in line until the election of the Fifth Labour Government and the increase in the top personal tax rate to 39% in 2000.

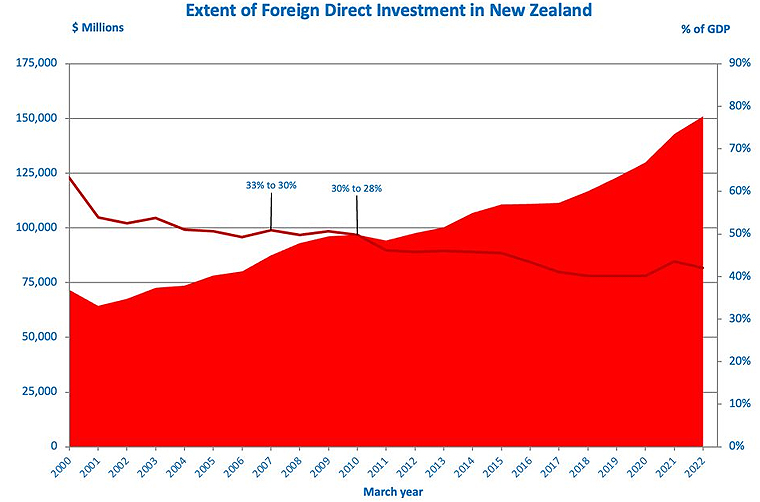

There have been a couple of corporate tax cuts over the past 15 years or so. In 2007, the rate was cut from 33% to 30% and then in 2010, as part of the rebalancing that took place under Bill English with the increase of GST from 12.5%, the corporate tax rate was cut to 28% where it remained since.

As I've discussed previously, there has been a long running global trend towards lower corporate tax rates. But that has slowed in recent years, first because of the effect of the Global Financial Crisis and secondly, the fiscal shock to government finances because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, according to the OECD in 2023, corporate tax rates rose generally across the board. Nevertheless, we are out of sync at the headline rate level.

More to investment than the corporate tax rate and will it work?

A lower corporate tax is undoubtedly attractive. However, the tax rate needs to be seen in context with what other incentives are available. Overseas companies and investors are very focused on what else might be on the table. A lower company tax rate would certainly be attractive, so the suggestion has been met with enthusiasm by some. Others are a bit more sceptical. Economist Ed Miller noted that when the effect of the corporate tax cuts in 2007 and 2010 are considered there does not seem to be any significant increase in foreign direct investment as a result.

The last tax working group didn't see overwhelming evidence to support the theory that lower tax cuts at lower corporate tax rate would attract investment.

Problems and an alternative

There's a flip side to this though, and it's tied into the Government's intention of restoring a surplus. Our corporate tax rate is not only above the OECD average, but our corporate tax take is also high by world standards. According to OECD statistics, 14% of the total tax receipts in New Zealand for 2022 came from company tax, whereas around the OECD the average is 12%.

So, if the Government, in an attempt to boost economic growth, is going to cut the corporate tax rate, it must then look at other alternatives to replace the lost revenue. One of the things it did back in 2010 and which it has already repeated, was to remove depreciation on all buildings. Depreciation for commercial buildings was restored under Labour but then removed again from the start of the current tax year on 1st April 2024.

A counter argument to the Government's proposal for corporate tax cuts would be that enhanced depreciation allowances, including restoration of commercial building depreciation, which would include factories, might be a more effective approach than across the board tax cut.

How to replace lost tax revenue?

But if the Government is thinking of a corporate tax cut, and that does seem to be the case, what counter measures could they take to ensure that it is not fiscally too draining on the resources? One option might be that the availability of imputation credits may be restricted. For example, it might be that you can elect to have a lower corporate tax rate, but you imputation credits are no longer available to for shareholders.

As an aside, imputation (sometimes called franking) credit regimes were very popular during the 1980s, but gradually fell out of favour over time, mainly because or in part because the European Court ruled that imputation credits or franking credits have to be available to all shareholders resident in the EU. After the German government lost this case its response was to heavily restrict the use of franking credits.

Change the tax treatment of Portfolio Investment Entities?

Another option might be to look review the taxation of portfolio investment entities held by persons with effective marginal tax rates above the 28%. To quickly recap, Portfolio Investment Entities (PIEs) have a tax rate of 28%, equal to the company tax rate, which is also the maximum prescribed investor rate for individuals. So, there is actually a tax saving opportunity for individuals whose other income is taxed above the 28% rate for PIEs.

The Government might look at this, decide that will no longer apply and instead income from PIEs will be taxed at the person's marginal rate. That could raise sufficient sums to partially offset the effect of a lower corporate tax rate.

The Finance Minister also mentioned reforming the Foreign Investment Fund regime, which is currently being considered by Inland Revenue and made some encouraging sounds about that potentially being an option.

We shall see. No doubt there’s a lot of work going on in Treasury and Inland Revenue looking at these options. All will be revealed in the Budget on 22nd May.

A threat to our Digital Services Tax

As covered in our first podcast of the year, one of President Trump's initial executive orders withdrew the United States from the OECD Two-Pillar international tax deal. I drew attention to the second paragraph of that Executive Order, which directed the US Treasury to consider taking actions against other jurisdictions for tax actions which are potentially prejudicial to American interests.

Vernon Small, who was an advisor to the former Minister of Revenue, David Parker, now writes a weekly column in the Sunday Star-Times has picked up on this point noting that “Treasury has budgeted to rake in $479 million between January 2026 and June 2029 from a 3% Digital Services Tax (DST) on tech giants like Google and Meta.”

This, according to Small, “is an heroic piece of forecasting given current uncertainties and the provision for delaying collections until 2030 if progress is made on a multilateral approach through the OECD.”

And then the crunch point:

“Trump has bosom buddies in high places in the industry with Elon Musk first amongst them, and Mark Zuckerberg making a play for the new US administration's affections.

Trump has promised to retaliate against discriminatory or extra-territorial taxes aimed at US interests. So the DST could be a prime target.”

Vernon Small is underlining the potential threat to our revenue base and our sovereign right to tax. If the OECD deal does fall over there are a number of countries including Canada, no longer America's best friend, it seems, with DSTs ready to go. So there's a whole potential for a tax war.

The Trump threat to tax administration

But equally worryingly, coming out of the United States is something about the question of bureaucratic independence from the executive. This might sound an arcane issue but it's actually quite important to the independence of tax authorities.

One of the first actions of the Trump administration was to sack 17 Federal Inspectors-general. There's also a move to put all Federal Government employees on the basis that they serve at the pleasure of the President. This would mean that an employee could be fired without the need for cause as the American terminology puts it.

Project 2025’s Schedule F

The implications of this have been picked up by Francis Fukuyama, the author of the famous The End of History essay written in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War.

Writing for the Persuasion Substack under the title Schedule F is Here (and it’s much worse than you thought) Fukuyama wrote:

‘ “For cause” protection means that the official cannot be removed except under specific and severe conditions, like committing a crime or behaving corruptly.And now many individuals have been moved, in effect, to Schedule F because they are said to serve at the pleasure of the President.

Consider what this may mean if Trump hand picks a new Internal Revenue Service chief, that individual can be pressured by the Government to order audits of journalists, CEOs, NGOs and NGO leaders. Removal of Inspectors General will cripple the public’s ability to hold his administration accountable.’

Trump’s decision to move all Federal employees to Schedule F status is a step towards autocracy. What perhaps we all need to keep in mind is that the separation between the Commissioner of Inland Revenue and the Minister of Revenue is actually incredibly important. Yes, at times the Inland Revenue might do something which probably might embarrass the Minister of Revenue, but he cannot directly intervene in Inland Revenue’s operations.

A key part of a well-functioning democracy is that civil servants can act independently from their nominally political superiors. Fukuyama is right to say we should therefore have some concern coming at what's happening in, in the United States because it does seem to be centralising power very rapidly around the President. The.potential for mischief is therefore enhanced as a result, and don't think that such a step ultimately doesn't have tax consequences.

Latest on the changes to the United Kingdom ‘non-dom’ regime

On a more positive note, last year I discussed the changes to the so-called ‘non-dom’ regime in the United Kingdom. This is where persons who are not domiciled in the UK have a special basis of taxation. Basically, they're not taxed on income and gains which are not remitted to the UK.

This is a significant concession which is ending with effect from 5th April this year when it will be replaced by something which is more akin to our transitional resident’s exemption. This is pretty important for the approximately 300,000 Britons like me who've migrated here, plus the significant number of Kiwis who have assets in the UK or family going to the UK but have retained assets here. All of this group are potentially within the scope of these reforms.

There's been a fair amount of push back on the reforms together with concerns that there will be a flight effect as wealthy, ‘Non-doms’ leave the UK. The UK Labour Government has been under pressure to make some changes to the proposals.

In response, the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Finance Minister) Rachel Reeves announced a concession (ironically at the gathering of the super-wealth at Davos) which will increase what's called the temporary repatriation concession.

This concession will allow non-doms a three year window to pay a temporary repatriation charge on designated foreign income and capital gains so that they can subsequently be remitted to the UK without any further tax. The temporary repatriation charge will initially be 12% before rising eventually to 15% in the year ended 5th April 2028. For comparison, without the concession remitted income would be taxed at rates up to 45% and remitted capital gains would be subject to capital gains tax at 24%.

There's a lot of opportunity here for potential tax savings for those who could be affected or will be affected by the proposed change to the non-dom regime. We're still working through all of the implications but we will be updating our clients and bringing you developments as they arise.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day

4 Comments

How can we continue operating with ever decreasing corporate tax rates in this world to try and incentivise foreign investment? Eventually it reaches a point where the costs outweigh the benefits and there are limits to how low this can go on for and how low they can go. Businesses have a certain level of mobility in being able to up sticks and relocate to countries with more favourable tax rates, however not all, and to continue longer term to pander to large conglomerate interests will not be in the benefit of NZ. Said businesses are aimed at profit alone, they do not care about the welfare of NZ and would easily up and go if anything changed that did not favour them.

Players like Facebook and google already strip revenue out of NZ Operations via intercompany transfers and fees, so that the NZ Entity pays virtually no tax, and tax is paid in Ireland where its 12%.

Nothing will change there at all.

I predict accounts will make money as if the corp tax rate is lower then personal tax rates the incentive will be to retain profits there.

Wouldn't surprise me at all if they raise GST, a kick in the guts to the working class who has already been beaten repeatedly in favour of a gluttonous ownership class.

People often say you can't raise taxes or there will be capital flight. That's why you tax assets like the rates are almost such a tax. Try take your land and property overseas. Same could be done for other immobile assets.

To ignore capital growth outpacing wages means the rich will eventually own everything, there will be no middle class and society will descend into violent crises. Overproduction of elites and imiseration of working people has almost always resulted in wide spread violence and societal crisis.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.