By Rabah Arezki and Partha Sen*

At first glance, the Indian economy appears to be thriving. Since 2000, annual GDP growth has averaged 6%, largely fueled by the service sector. High-value-added services, in particular, have emerged as major drivers of exports and GDP growth.

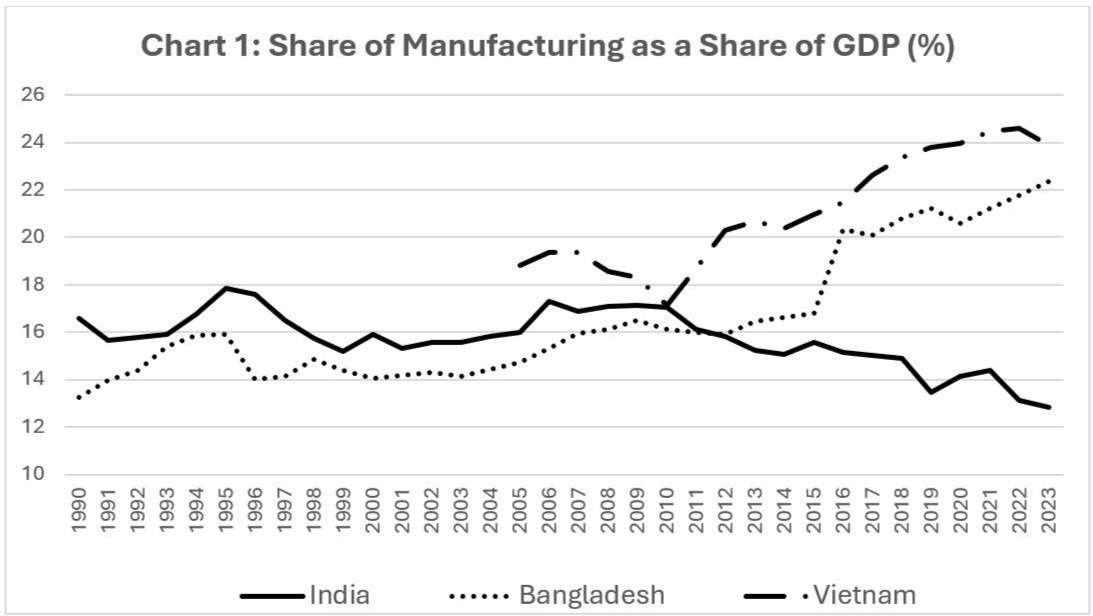

But despite this impressive record, India has failed to replicate the rapid industrialisation of other emerging economic giants like China. In fact, as Chart 1 shows, the country has experienced significant deindustrialisation over the past few decades, jeopardising its long-term growth prospects.

Compounding the problem, agriculture’s share of GDP has steadily declined, even as the sector continues to employ 43% of the workforce. This trend reflects pervasively low labour productivity in agriculture – especially in the large informal sector – relative to the non-farm sector.

As China’s labour costs have increased, many analysts anticipated a massive expansion in India’s industrial base. With its vast supply of labour, India appeared poised to attract international investors seeking a lower-cost manufacturing workforce, in turn fostering economies of scale. But while the manufacturing sectors of much smaller economies like Bangladesh and Vietnam have grown rapidly in recent years, India has fallen behind.

Commentators often point to inhibiting factors such as India’s rigid labour laws, high unionisation rates, inadequate infrastructure, and land-titling system. But though these issues have undoubtedly played a role in constraining certain industries, such explanations fail to account for the fact that India’s 28 states and eight union territories have considerable autonomy over labour, land, and infrastructure policies. If labour regulations or unionisation were the primary obstacles to industrialisation, some states would have adjusted their policies to gain a competitive edge and emerge as industrial powerhouses. But despite significant policy and structural differences between states, this has not been the case.

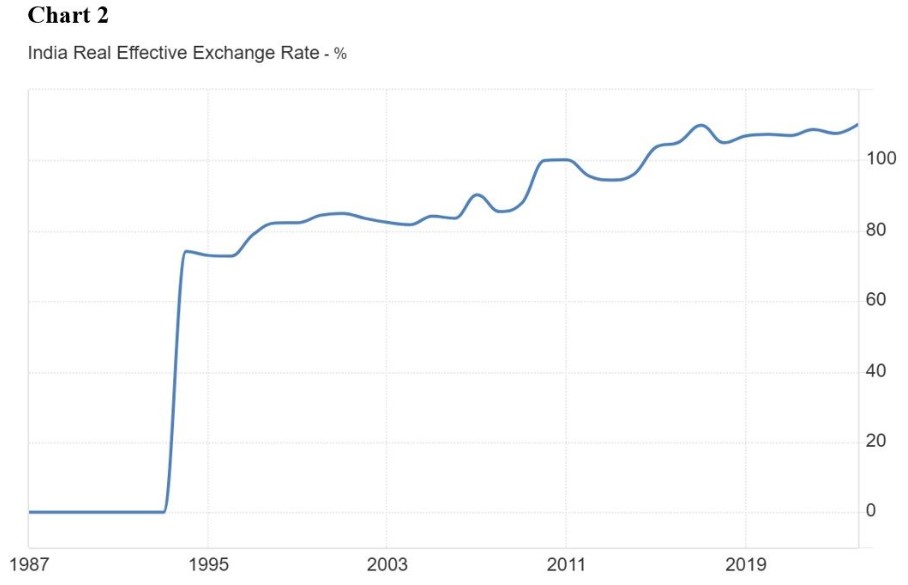

A more plausible explanation lies in the shift in India’s real exchange rate following capital-account liberalisation in 1991 (see Chart 2). These reforms, introduced in response to a balance-of-payments crisis, caused the rupee to appreciate, eroding the competitiveness of Indian exports and deterring industrialisation across all states and territories. Although some reversal of portfolio investment flows currently is occurring because of high US interest rates, allowing the currency to depreciate, that will likely reverse again.

Moreover, capital inflows triggered by India’s capital-account liberalisation have boosted demand for domestic assets, fueling a stock-market boom and driving up real-estate prices. This excess demand was partly offset by nominal appreciation, which led to a revaluation of domestic assets relative to foreign currencies.

To be sure, there are multiple factors behind India’s stalled industrialisation. But many of the country’s challenges on this front can be traced to an imbalance between aggressive capital-account liberalisation and inadequate trade reforms. India’s approach mirrored that of several Latin American countries, which liberalized their capital accounts before reforming their trade policies. By contrast, France liberalised its capital account only in 1989, after establishing a robust trade framework.

Although India reduced some tariff barriers after joining the World Trade Organisation in 1995, non-tariff barriers remain pervasive. These trade frictions have skewed capital inflows toward portfolio investments, fueling the housing boom and boosting consumption, thereby exacerbating India’s structural imbalances.

In other words, India’s industrial woes can be attributed to a form of “Dutch disease,” which originally referred to the economic impact of currency appreciation in the Netherlands following the discovery of the Groningen gas field in 1959. In India’s case, exchange-rate appreciation has increased the import content of domestic consumption, crowding out investment and generating rents for import monopolists, which have become powerful lobbies opposing domestic manufacturing.

Given that job creation remains essential to the well-being of the vast majority of the population, the costs of this “Indian disease” could be enormous. But resolving India’s industrialisation puzzle is no easy task, as the country’s business and political elites have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Reversing this trend will require a firm commitment to shifting capital flows toward foreign direct investment and removing trade barriers, including those that currently support monopolistic importers. That said, reintroducing capital-account controls risks undermining financial stability and deterring international investors. A thoughtful, strategic approach will be crucial to managing these trade-offs and fostering a more balanced, sustainable economy.

By reforming its capital account with a Tobin-tax-like capital control to disincentivise speculative flows, and by tackling longstanding trade imbalances, India could send a clear signal that it is serious about becoming a global manufacturing powerhouse. While the Indian economy faces numerous other challenges, taking these steps would create new opportunities for domestic and international investors, as well as for the millions of Indians eager to help transform their country into the next China.

*Rabah Arezki, a director of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), is a senior fellow at Harvard Kennedy School. Partha Sen is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Delhi School of Economics. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025, published here with permission.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.