This is a re-post of an article originally published on pundit.co.nz. It is here with permission.

We seem to be entering an era of populism, in which leadership in a democracy is based on preferences of the population which do not seem entirely rational nor serving their longer interests. The re-election of Donald Trump is just the latest example

Professionally, I found the British people’s voting for Brexit the most disturbing (52 percent voted to leave, 48 percent to remain, on a 72 percent turnout). There was a compelling case that the British economy would be damaged by Britain leaving the European Union (although not as quickly as some claimed). One might favour ‘Leave’ because it would give Britain more control over itself, for international economic intercourse compromises national sovereignty. But the tradeoff is that cutting back trade reduces economic prosperity. Much of the public chose to ignore the tradeoff when they voted. Subsequently they found that the sovereignty gains were small, while the British economy has performed badly. An increasing proportion of ‘leavers’ regret the decision to leave. The economic analysis proved correct.

Populism is sometimes characterised as ‘the people’ rejecting the ‘Establishment’. During the Brexit campaign there was a strong undercurrent that since the Establishment supported ‘Remain’, the policy must serve them to the detriment of ‘us’. They now know that closer British involvement with the European Union was beneficial to many of them too.

It is easy at this stage to dismiss people taking a strong line against the Establishment as ignorant or worse. Recall Hillary Clinton muttering that many of the Trump supporters were ‘deplorables’ and there will be equally dismissive explanations of those who voted for Trump’s second victory – ‘racists’, ‘sexists’, ‘fascists’ ...

It might be wiser to recognise that these people have concerns which they may badly express, which they may badly diagnose, and for which they may have badly thought-through policy responses. But even so, those underlying concerns are real enough. There is no point in ignoring them and then being shocked at the following election when the holders again vote against the Establishment and even against their best long-term interests.

How often does one hear preaching rather than engaging with the audience? How often does one find that the preacher’s argument is self-serving? That does not mean that the argument is always wrong, the preacher is just not connecting. The case against Brexit was not wrong as we (almost) all know with hindsight; it was badly presented.

I’ll leave others to tell us about the populist vote which has returned Trump to power, and I’ll leave you to decide whether the opinions are self-serving or based on too narrow a perspective and information. Instead, here is a New Zealand example about how a government was not listening to even its own people.

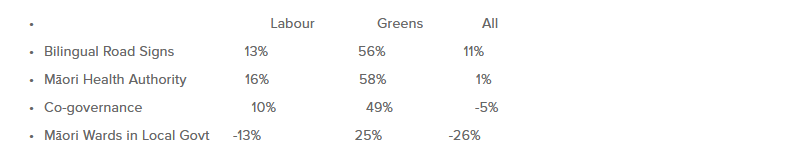

In August 2023 Talbot Mills Research surveyed voters on their views on some non-economic issues. Four responses are revealing. The scores here are the percentage favourable less the percentage unfavourable by party voting intentions. The focus is on those intending to vote Labour but the equivalents for Green and All voting intenders are included for comparison.

There was not a lot of enthusiasm among Labour voters for their party’s policies, especially when you compare the Green responses. The survey took place a few months before the 2023 election, where the party ad lost half of its 2020 support. Presumably the majority of the Labour leavers had views more like the last column of all voters, who were even less enthusiastic.

One must conclude that the Labour Government seemed hardly to be listening to its own supporters – let alone the nation as a whole. One is reminded of a parallel instance under the Lange-Douglas Government, when a small group of senior cabinet ministers pursued (neoliberal) policies which were an anathema to the party supporters. A Talbot-Mills survey in August 1990 which asked questions about Labour’s economic policy is likely to have shown a similar lack of enthusiasm.

It was a time in which half the population had no increase in their real incomes between 1986 and 1998, 12 years later. Around a third had to wait twenty-odd years before they got an income boost. But there was nary a mention of their struggles by the experts and acolytes of the Establishment, whose incomes continued to rise under the neoliberal policies of the time. I leave it to the elite to reflect whether they should feel guilty about their neglect; the point here is that they were not listening.

What would we hear from the non-establishment were we to listen? I am hesitant to answer that question. It is just too easy for the opinionated to pretend to listen and report their personal prejudices. However, allow me to raise the possibility that rising material GDP does not always make consumers feel better off, despite our having been indoctrinated into assuming it does. GDP measures output, whether the output be goods or bads.

For example, when Europeans first arrived in New Zealand, they wanted produce like flax, timber and food. Maori increased their production in order to acquire guns and other European goods in exchange. GDP increased but the guns led to the chaos of the Musket Wars which devastated the Maori population. This extreme example reminds us that increased material possessions need not lift wellbeing.

It may be that increased material consumption and possessions in the first half of the post-war era was associated with people feeling better off. But that may be less true in the second half. Hence the turning to populist demagogues who promise better outcomes (even if the promises do not get fulfilled as in the case of Brexit and, as seems likely, with some of Trump’s promised policies).

It is possible that once consumers have met reasonable material needs – not all have – additional consumption is more concerned with esteem needs so that there are few realised gains from just keeping up with Jones. (The implication is that traditional theory which equates consumption with wellbeing no longer applies.)

The populist phenomenon may not be only economic. The Talbot-Mills survey explored cultural responses. Another possibility is that many people are finding the rate of change is accelerating and they are finding it increasingly difficult to cope. That may explain why populism is currently dominated by conservative parties in affluent economies – Boris Johnson’s Conservatives in Britain, Trump’s Republicans in the US, New Zealand’s most populist part in NZF led by Winston Peters. (MMP may disperse the populist capture of a single dominating party; I resist going down some interesting consequential paths.)

Whatever the reasons for the rise in populism – there are more – it presents a challenge to liberal democracy. The challenge will not be resolved by ignoring the underlying concerns until the run-up to the next election and calling their holders ‘deplorables’ when they vote against the Establishment.

*Brian Easton, an independent scholar, is an economist, social statistician, public policy analyst and historian. He was the Listener economic columnist from 1978 to 2014. This is a re-post of an article originally published on pundit.co.nz. It is here with permission.

27 Comments

'which do not seem entirely rational nor serving their longer interests'

Brian is describing the 'discipline' of Economics. It flies blind - as he does - to energy and resource throughputs.

He therefore has no clue. And had had many opportunities to redress that. Applies to more than him, too. Why?

The stage of planetary depletion we have reached, is impacting not only the 3rd world, but is now intruding well into the middle classes of the First world. Only those who don't count the real (stocks, depletion-rates and entropy) will not understand why.

As an agnostic, hate to say it Power but the biblical end of times seems to fit well with the narrative surrounding overpopulation and energy depletion / planetary degradation. My colleague who heads up a national business for global FMCG company is going through an existential crisis right now.

The economics profession is a broad church PDK. It even includes one of your heroes Thomas Malthus.

Here is the Wikipedia description of him.

Thomas Robert Malthus FRS (/ˈmælθəs/; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

The current version of economics, rubbishes Malthus.

Diversion alert...

Indeed they do...though it may be wise to consider that it is very human to relate future conditions to the known past....the 'blip' though an instant in geological time is the lived experience of all until now.

No PDK you miss the point. BE is making a clear case that the political establishment is not listening to the people. He is not talking about the background issues. He is identifying that this government has forced all government departments to save money, but despite stating it is not to impact the frontlines, these measures must and have inevitably impacted the frontlines. Without a promotion most frontline workers, especially those on IEAs will not get much if any pay rise this year, a time when recent inflation peaked above 14%. In every respect they have universally disrespected those frontline workers. Frontline public service jobs are not well paid although back office and managerial roles generally are. ( I would repeat my past assertion here that in the public service if you are not a frontline or 2nd line worker, then it is highly likely your contribution to delivering the service your department is funded for is likely inversely proportional to the size of your salary) To argue they can leave their jobs and go into the private sector, but many of the public service jobs are specialist roles with few opportunities in the private sector, and besides recent news identifies that private sector job markets are essentially collapsing. The impacts of their policies on the private sectors are less clear cut, but not much different.

While the government are imposing these constraints on their workers, note that they are not doing the same to themselves. They are not LEADING, they are directing. Big difference.

The postgrad qualified bureaucratic elite based in both Wellington and Washington DC work and live in their own rather narrow priority and prejudice reinforcing echo chambers. They are reinforced by a media system which orbits closely around them. And they always seem shocked - shocked! - that the unwashed masses who do not subscribe to their particular beltway perspectives and predilections have the audacity to voice a different view.

The unwashed masses are reacting to pressure.

That truth (of the pressure) is fiercely resisted by folk who then think they have the right to claim 'journalist' status.

And largely by those who see themselves 'winning' in the current system; anyone in the high-end-first-world income bracket.

B E : "many people are finding the rate of [cultural] change is accelerating and they are finding it increasingly difficult to cope."

The implication being that there's an implicit inability to change.

Perhaps, more likely, the people don't accept the wisdom (such as it is) of the changes being promoted; that the new gender and race theories or mass illegal immigration are not only wrong but dangerous.

"Populism" isn't a challenge to democracy; it is democracy.

Populism is sometimes characterised as ‘the people’ rejecting the ‘Establishment’.

The ‘Establishment’ is either malevolent to the population and/or too incompetent to manage it. The best anyone in the West has done since WW2 is manage the decline. It gets covered up and the real consequences get delayed but none of the problems ever get fixed. Trump got back in because the ‘Establishment’ did not find someone half competent to put up against him. Society is wanting someone to "seize" control to fix it (not that Trump can or will).

Our Establishment media are the facilitators. They have found themselves with a lot of influence and are just interested in managing the decline too.

P.S. Brexit was designed to fail at every step. The ‘Establishment’ wanted it to fail and eventually succeeded. There are no economic lessons here just malevolent political incompetents.

The neoliberals won big in the 1980s. Their explicit intent was to...

- Break trade unions. Directly through violence and by ensuring that a new economic approach became dominant - one where the answer to price instability was always and everywhere the removal of workers' bargaining power (increased unemployment).

- Free finance. The rich get rich off other peoples' debt but credit wasn't flowing into the economy fast enough to satiate the appetites of the wealthy. So, the neoliberal ghouls pushed for financial deregulation - ensuring a flow of brand new money into the economy. The influential economists at the time didn't understand banking (many still don't), so they didn't work out what was going on.

- De-regulate. It was crystal clear in the 1970s and 1980s that the world was heading off on a completely unsustainable path. The neoliberals argued that deregulation was necessary to support growth, but, don't worry, market mechanisms can be used to prevent pollution, harm etc. This worked to a degree for acid rain and ozone (because the same companies that were threatened could make money from the alternatives) but it failed completely for carbon, and biodiversity never got a look in.

- Sideline Govt. The smaller state was sold as the key to success - the market will provide etc. Anything else is socialism. Right wing economists started to conjure up ridiculous theories to support the small-state, neoliberal agenda - Laffer Curve, Riccardian equivalence, Phillips Curves, etc.

The result has been a disaster for the working-class - precarious work, falls in living standard, huge inequality justified by trickle-down. It's also been an absolute disaster for the planet. The neoliberal elite used 'othering' to ensure that workers didn't put two and two together - your plight is not the fault of the capitalist class my brothers, it's the immigrants / beneficiaries / cheating Chinese Govt etc (delete as appropriate)

A Labour Party that spoke to and for the working-class would clean-up. But they are stuck within the neoliberal paradigm and getting pushed by smarter right-wing forces into arguing about culture war issues. They need to break out.

I worry that Labour parties have been hollowed out and the only ones left are neoliberals who have no interest in doing the kinds of things necessary to help the majority of people. At least in the English speaking world.

Not quite how it works.

Labour were just about a different cohort wanting some of the cake. The winners reacted to increasing cake-scarcity, by doubling-down on ownership. That has continued, and we see it in the current 3-Clown Circus; property rights being a cornerstone concept.

The bigger problem is the dwindling amount of remaining cake - that reduction will eventually collapse the system the elite need, to track their ownership. Which is the system the poor are reliant on too.

The question is how do 'the left' (i am unsure if that exists anymore) break out within a global system that demands ever increasing private debt?

As far as I can see that cannot occur until such time as the system either collapses or is radically reformed.....I expect the former.

You do, and I do - but Easton hasn't a clue.

And the reason is he sees flows - backcasting being the only way you can - rather than stocks. As do they all - even when pressed. Especially when pressed...

Nobody pushed Labour into being absolutely garbage last time around. They did that to themselves. The urge to portray ones self as the saviour for the poor and downtrodden only to wipe your feet with them is their problem. They couldn't execute and ultimately didn't care. If they did, they would have done something about it.

Instead they ran up huge debt, barely moved the dial on poverty and presided over the most rapid decline in our standard of living in the post-9/11 era. Running huge centralisation exercises and making arbitrary constitutional changes to the function of the public service mattered more than anything to do with the working class, and has nothing to do with being baited into arguing about culture wars.

To implacate blame on one group over a six year period and only mention the debt is naieve at best. To even move the dial on any of the social and inequality problems evident in New Zealand would take at less a decade and to see longer term outcomes a generation will be required, maybe even longer. You can't just trow money at it - that helps but you need people who can walk the talk - they have to be trained and gain experience to make a difference. Problem is no people to do the work required.

The turn to populism has been a long time coming and was predicted by Michael Sandel in his 1996 book Democracy's Discontent.

He outlined the concern that the belief that markets, cost benefit analysis, and other technocratic measures could provide a value-neutral solution to the moral choices of governance. This would hollow out public discourse as it means governance should be determined by technocratic expertise rather than public deliberation of contested questions of justice and the common good.

Michael worried that this would lead to a moral vacuum which would sooner or later, result in:

politicians who would promise a politics that would shore up borders, harden the distinction between insiders and outsiders, and promise us a politics to take back our culture and to reassert our sovereignty with a vengeance.

A recent survey showed that Trump supporters didn’t watch tv news or read newspapers or other news. They got news from YouTube and Social Media.

if the people that are voting aren’t receiving accurate information then they won’t vote in an informed way (conversely they will vote in an influenced way)

People are also busy and time poor making reading more challenging. So podcasts and broadcast radio are important channels for information.

The glues that held societies together are changing. Unless governments or societies more in general adapt and communicate/collaborate better then those societies will get the mood of the population.

"Trump supporters didn’t watch tv news or read newspapers or other news. "

Part of a massive collapse in "the legacy media" I suspect, Tim. About 70% of us (here and in the US) now have little or no faith in media; it is perceived as biased, manipulative and dishonest. The aggregate bias in the media (including centrist and right leaning) really showed, just recently, in the stories and opinions they were propagating by MSM: about 90% of Trump stories decidedly negative compared to 15% for his opponent.

Traditional media are committing suicide as we speak. We ( adult humans) have an instinct for BS that is often aroused when only one side of an argument is presented. An evolved feature that reflects the complimentary nature of reality?

I recently challenged David Chaston on that very point.

I hope he reads your post.

Surely this is the very reason interest.co.nz is becoming increasingly influential. Ordinary Kiwis starting to figure out that the bank economists and real estate wannabes being interviewed in the mainstream media are not telling the whole story (to put it mildly) and the newsrooms are letting them get away with it.

re. biased, manipulative and dishonest media, Katie Bradford gave the game away just before the 2014 election when she said on TV: "No matter what we say, no matter what we do, we can't shift the polls".

It was a beautiful moment.

Anthony Trollope, writing in the 19th century, highlighted the inherent agendas of media outlets. At some point in history, people forgot that the media has always had an agenda, and invented a romanticised "4th estate" paradise. Now the scales are falling off, but we're not really that different from our brethren in the 19th century.

What the "fools, suckas and chumps" who get their news from social media instead of the MSM have conveniently forgotten is that the purveyors of their news have their own agenda too, and it might not be the one their customers think it is.

The vast majority of media is owned by the extremely wealthy (like everything). It was never about Harris vs Trump, Democrats vs Republicans. It's about maintaining a situation where those two options are the only options. You have different flavours of neoliberal ideology making more or less concessions to the extremely wealthy. That's your only two options for who is in charge in every Western country. Throw in some identity politics to try and show difference, but never class.

I could certainly believe Trump wasn't their first choice, but in the end he has given out huge concessions to the wealthiest Americans.

Any genuine threat to this is quickly slandered out of the running like Corbin was in the UK.

Social media could have been an antidote to this, unfortunately it has been extremely well harnessed to get people very fired up about class dividing issues (take your pick they'll put something in front of you that upsets you).

The vast majority of media is owned by the extremely wealthy (like everything).

For the most part that ownership is not via extremely wealthy individuals. It is by massive investment corporations like Blackrock, Vanguard and Fidelity and they are far more powerful and influential than even the richest individuals like Gates, Bezos and Musk. And we have seen that the track record of these investment corporations has been to push a pro Democrat left wing agenda via initiatives like DEI and ESG on to the boards of all the corporations that they are shareholders of.

End stage capitalism, where there isn't much of a food chain lest as the one largest predator consumed all else around it, so now farms it's own food for survival of its insatiable appetite

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.