This is a re-post of an NZIER paper. The original is here.

After years of denial that a crisis was unfolding, the moment of truth has well and truly arrived. In this NZIER Insight, we propose five priorities to get the system back on track and heading in the right direction.

The health system crisis is playing out daily everywhere from emergency departments and GP clinics across the country to the boardroom of Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora. Health professionals are burnt out, and New Zealanders’ faith in the health system is being lost.

This is a key issue the government will want to address before the next election. But will it address the underlying systemic issues or just kick the can down the road?

Costs are a key focus, but productivity is the key issue

Our health system crisis – like those affecting public health systems around the world – is often characterised as a cost crisis. The cost of delivering healthcare has reached the point where it no longer appears to be affordable. Doctors cost more and more, pay equity settlements translate into huge public sector outlays and the expected cost of building and maintaining the physical infrastructure that services rely on has reached epic proportions 1 (NZIER 2024).

The current crisis was predicted by economist William Baumol, whose work starting in the 1960s described the economic outcomes of industries having different rates of labour productivity growth. He later identified health as one of a number of “stagnant” industries – labour-intensive industries with fewer opportunities for productivity gains than other sectors such as manufacturing. He argued that, because health services are nevertheless needed, health labour costs would have to keep pace with labour costs in sectors that make more significant productivity gains.

The result is rising costs for services even without any improvement in quality – a phenomenon he coined “cost disease”.

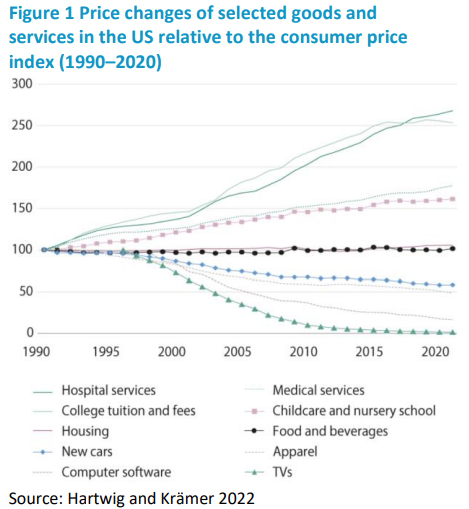

Baumol explained that this is why, even though many other goods and services become more affordable over time, healthcare does not. This was compellingly shown using US data on various industries’ price changes relative to the consumer price index, an updated version of which is shown in Figure 1 below.

Baumol’s theory predicts that health expenditure per capita and as a share of GDP will rise relentlessly, even with all else remaining constant.

A cost containment imperative?

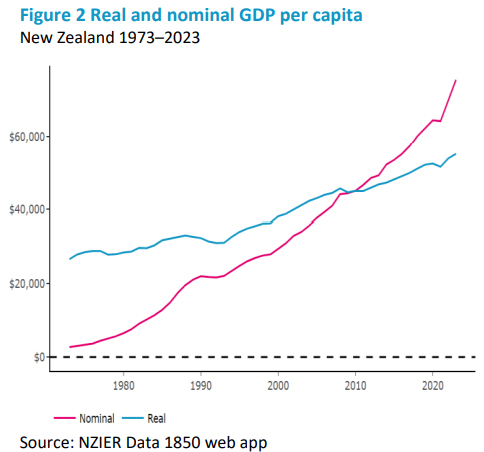

While cost disease is inevitable, the unaffordability of healthcare is a “fiscal illusion” (Baumol 1992). As long as there is economic growth (which there is, despite short-term hiccups – see Figure 2 below), healthcare becoming a rising share of GDP should not be alarming – except to those with political reservations about “big government”.

Baumol identified that the eventuality of big government implied by cost disease – and the known political unacceptability of this – pushes governments into cost containment mode with the inevitable consequence of:

“… deterioration in the quality of the service and, ultimately, withdrawal altogether of a service that is presumably valuable to society.” (Baumol 1993)

But cost disease is not the only cost driver

Baumol’s cost disease and related predictions should be concerning. Recent empirical research appears to confirm that cost disease is real (see, for example, Hartwig 2008 and Colombier 2012), but the most recent studies confirm that costs are more heavily driven by traditional demand drivers (e.g. population ageing, socioeconomic determinants of health etc.) supply-side drivers (system design features), and technological progress.

This means some growth in health expenditure is likely to be unavoidable as it is driven by productivity gains outside the health sector and by uncontrollable factors such as population ageing, so an increase in Vote Health is warranted to maintain services.

Equally importantly, some cost growth is driven by choices about social and economic conditions (especially for the worst off), system design and how the system responds to technological progress. The health sector does not lack opportunities for productivity growth, but rather it lacks support to take opportunities that are available2 and has built-in barriers to achieving better outcomes at lower cost. 3

So it’s time to make some choices

We propose that an increase in Vote Health is now necessary. However, the government should resist the urge to contain costs by only addressing short-term resourcing issues – a move that would only kick the can of our creaking 20th century system down the road and reducing our ability to afford real solutions: Like spending all your money on buckets instead of fixing the leak in the roof.

We recommend investment in five key priorities based on the principle that to minimise cost growth and increase long-term sustainability4 without compromising quality, the system needs to be efficient and flexible, and it needs to contribute to economic growth as well as being supported by it.

Efficient, flexible and productivity-focused system design

Efficiency means using lower-cost inputs if they can deliver the same or better results 5 . Flexibility means being able to change shape and structure easily as needs evolve and opportunities emerge to maintain efficiency over time. Contributing to economic growth means delivering services in a way that improves the productivity of the workforce both within and outside of the health sector.

Our recommendations envisage a fundamental shift from the current high-cost, bricks and mortar, medically dominated system towards a system that prioritises a broader, more flexible workforce backed by technology and treatment options that support community based care, all driven by decision making that reflects broader economic considerations.

The five solutions we need now

We recommend that the following five solutions are not only urgently needed but would improve system productivity so warrant an increase in Vote Health to achieve them.

1. Funding and resourcing a 21st century model of community-based healthcare

Primary care – the first point of contact in the health system expected to provide accessible, protective, preventive care and care coordination – has traditionally centred on general practice and care provided by GPs.

With population growth and ageing along with increasing recognition of the need for person-centred care, GPs are no longer able to play this role alone. People are struggling to access GP care, the sector is struggling to staff the traditional general practice model and it is not the most efficient way of meeting needs.

While GP clinics have struggled to meet needs within traditional service models and tight funding, NGOs across the country have been quietly driving innovation and implementing cost-effective solutions often involving high use of the non-medical workforce6, including a wide range of regulated and non-regulated health workers. 7 The NGO sector’s ability to deliver solutions for community-based care on the smell of an oily rag is proof of the potential for productivity improvement from scaling up investment in community-based health services and upskilling the community workforce, employable at a fraction of the cost of traditional primary care.

A broader workforce-based community model with alternative first-point-of-contact services8 is particularly urgently needed to meet the growing need for home-based care, rehabilitation and needs assessment as well as to support older people to avoid aged residential care and to receive end-of-life care in their own homes. It is also critical to maximising the opportunities that new technology presents for personalised prevention and remote patient monitoring.

Central to this change is the development of micro-credentialing and career pathways that facilitate upskilling and role transition. Basic skills that allow home health workers to assess a diabetic foot or a wound and education pathways that allow pharmacists to transition to a career in general practice by building on their existing skillset are the kind of workforce innovations that strengthen sector flexibility and efficiency as well as supporting equitable access to health sector careers such as has been shown for Māori nurses (Wiapo et al. 2023) and increasing workforce productivity (Holden 2023; NHS England 2023).

2. A strong back-end to the care continuum

Acute demand has been a significant and growing driver of overall healthcare demand for many years, and shifting population demographics are a growing contributor to this problem. While emergency departments (EDs) attract much of the focus on acute demand, recent research shows that New Zealand’s EDs are not crowded due to inappropriate presentations with minor ailments. 9 To the contrary, our ED utilisation rate is low by international standards with primary care largely doing an effective job of keeping people away from EDs if their needs can be met elsewhere (Jones and Jackson 2023).

The ED crowding we hear so much about is largely due to flow issues later in the care continuum. A key aspect of this is patients staying in inpatient beds longer than necessary, causing a phenomenon known as ‘bed block’ where admissions and transfers from ED cannot occur because there are no beds available in the wards (Jones et al. 2021). Bed block also contributes to long waits for planned surgeries and short-notice cancellations of these (Ardagh 2015).

Effective discharge planning and agreed principles are required to support timely discharge, including discharge by a broader range of staff (not just senior clinicians who are often not available).

Adequately resourced community-based discharge support teams have been shown to improve outcomes and reduce hospital stays and system costs (Parsons et al. 2018). New digital technologies enable acute care to be provided in and across more settings, bringing the broader workforce into play in reducing hospital stays (Dean et al. 2022). Aged care plays a key role in the care continuum for a growing older population, with a cost that is dwarfed by the cost of extended inpatient stays when aged care beds are unavailable.

3. A digital technology forward sector

Digital transformation is desperately needed to reduce costly, ineffective and inefficient communication barriers between services as well as between providers and patients, improve the information available to decision makers and support the adoption of technologies that enable remote patient monitoring and care by a broader generalist workforce (including self-care) (see, for example, Milani et al. 2017).

The health system has been creaking along with 2.3 percent of operating budgets on IT, of which 90 percent has been propping up outdated systems (Ministry of Health 2020). The lack of interoperability, access, security and system support for implementation of productivity-enhancing technologies is a major threat to the system. It keeps services tethered to costly and inconvenient physical infrastructure, keeps patients deteriorating in hospital beds instead of recovering at home10 (Kruys and Wu 2023) and condemns the system to a permanent struggle against workforce shortages due to the inability to ensure adequate support and oversight for a broader workforce to deliver care safely.

A modern, fit-for-purpose digital approach to health services requires substantial upfront investment in core infrastructure as well as support for adoption of specific digital solutions and ongoing maintenance. This is not cheap, but as shown by multiple studies (see, for example, Frakt 2019), this would improve productivity and cost-effectively increase capacity to address unmet need11 . Community based providers, including primary care, should be central to this transformation.

4. A social investment approach to support a productive workforce

Health economic theory identifies healthcare as both a consumption good that higher income increases demand for and an investment in human capital that supports the workforce to be more productive. But decisions about health services rarely take into account employment-related impacts.

The ACC approach, which incentivises prevention, early diagnosis and rehabilitation, is an important model for a health system facing a substantial demographic shift that will result in a dependency ratio never seen before where the dominant group has high health need. Published research has identified key health issues driving absenteeism, presenteeism and dependency on sickness or disability benefits, with mental health and musculoskeletal disorders being major drivers (see, for example, Bryan et al. 2020).

For long-term sustainability, health investment should focus on short-term workforce productivity (addressing mental health and musculoskeletal issues), long-term workforce productivity (investments in better prevention and management of long-term conditions) and children’s health and wellbeing, especially where it supports educational attendance and attainment and minimises long-term impacts. 12

As a growing share of the total workforce, the health workforce also warrants investment to lift overall productivity. Community-based health workers are a key group whose upskilling and greater involvement can offer both direct and indirect productivity impacts.

5. Increased access to medicines

Medicines play a critical curative and secondary prevention role in healthcare and will increasingly play an important primary prevention role as personalised prevention becomes commonplace. Medicines for high cost conditions such as those with high rates of hospitalisation or long-term impacts on productivity offer potential for significant returns on investment. From a decision maker’s perspective, medicines also typically come (at the point of application for funding) with robust evidence of impact, reducing the risk of losses from experimentation or failed implementation of innovative services.

Pharmac holds a list of medicines called Opportunities for Investment – medicines identified through Pharmac’s own processes as offering important clinical benefits and being cost-effective but that are not yet funded due to Pharmac’s strict budget constraint. As of late June 2024, there were 147 items on this list, representing a veritable Christmas list of golden opportunities that require only a budget increase to unleash.

Despite the abundance of opportunities presented by medicines, NZIER’s own analysis has shown that the government has reduced the pharmaceutical budget in real terms(NZIER 2022). The government should be committing to annual increases in the pharmaceutical budget to bring it closer to the OECD average of 1.4 percent of GDP from its current 0.5 percent of GDP (Shaw 2023).

A community workforce where appropriately trained professionals with increased scope of practice could make some medicines more accessible would support system flexibility, reduce the access barrier of needing to see a doctor, and reduce GP and specialist workload (such as increased pharmacist prescribing or optometrists delivering intraocular injections).

Choice is key

As Baumol worked through the implications of his theory, the “illusion” of unaffordability and implications of political concerns, he cautioned that there was real risk in choices that governments might make when faced with growing health costs and – rather befittingly for New Zealand today – warned that:

“… an unfortunate choice in this arena does indeed threaten to bring us an economy, in the words of the poet, ‘where wealth accumulates and men decay’.” (Baumol 1993).

The government seems confident that it can deliver on its promises of economic growth. That should equally give it confidence to break through the illusion that New Zealand cannot afford to spend more on its health system.

Notes:

1 Our previous work on Crown-owned health infrastructure shows that, under the current approach, the health system will need $100–115 billion over the next 30 years just for hospital buildings (NZIER 2023).

2 NZIER’s work on productivity (NZIER 2024) indicates that even the private sector needs government support. This would include many community-based providers, even those that are for profit.

3 For example, the case of kidney transplantation (NZIER 2021).

4 Solutions tend not to be sustainable in the long-run unless they are simultaneously technically feasible, institutionally possible, and politically desirable (NZIER 2016).

5 In the health sector, this is sometimes referred to as using constrained inputs more effectively.

6 Costa Rica’s health system is lauded for this approach.

7 The non-regulated workforce includes a wide range of occupations that are not regulated under the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003. This does not imply a lack of professional standards. Professional bodies and a range of other legislative controls provide a suitable framework for this workforce (Ministry of Health 2014).

8 Previous NZIER research has indicated an important role for physiotherapists and other allied health professionals (NZIER 2020, 2021).

9 Although progress made on reducing inappropriate ED presentations could be lost if primary and community care continues to be underfunded.

10 Delayed discharge from inpatient wards is associated with increased mortality, infections and depression as well as reductions in patients’ mobility and daily activities (Rojas-Garcia et al. 2017).

11 Costa Rica’s “army of community health workers” (Exemplars News 2022) and “community health workers ‘plus’” equipped with supportive digital technology (VanderZanden et al. 2021) is a key reason for its health system’s high return on investment.

12 Such as expansion of community-based throat swabbing and fast access to antibiotics to prevent rheumatic fever.

This is a re-post of an NZIER paper. The original is here. It includes a full set of References and links.

Sarah Hogan is Deputy Chief Executive (Wellington) & Principal Economist, at NZIER.

31 Comments

For an economist - and being one is to start from well back on the grid - this is a mostly-reasonable piece.

'But decisions about health services rarely take into account employment-related impacts.'

Wrong; they've been triaging health-access for 40 years (pers com, 1983) vis-a-vis employment/ability.

Big-picture, humanity is 6-7 billion overshot, on a real-sustainability basis. So we need a big-picture road-map for getting back to sustainable/maintainable levels of consumption. That has implications for 'productivity' (which it isn't: what economists call productivity, is really energy-efficiencies) and for 'output' and ultimately, for what we apportion to what - including to health.

It’s a really good piece, well done NZIER.

I also think NZ’s high cost of living, relative to income - and especially housing - is a major factor, not addressed in the article (not a criticism - the article was focussed on the health system itself)

And yet private health organizations and hospitals appear to provide excellent levels of care with administrative efficiency.

Rather than trying to figure out where the public system is going wrong, leading to reams of often unhelpful abstractions, why not just look at what the private health care system is doing right?

This article is replete with broad and aspirational statements. It also does not consider specific patent issues - for instance, the proportion and the absolute level of costs spent on administration versus direct medical care (doctors, nurses, laundry/cleaning, medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, record-keeping/IT) as between the public system and private healthcare providers.

This leaves open the question of whether it would assist to simply disestablish a large proportion of the 12 -odd layers of thousands upon thousands of bureaucrats and administrative positions in the public system, and reallocate that money to such direct costs instead.

Regardless, consideration could also be given to ensuring every child at school attends a couple of classes at some point (in say form 4 or 5) given by a doctor/nurse about the importance of regular medical check ups and getting early advice from a GP whenever unsure.

I don't think you can compare the public and private health organizations in NZ.

The private system only deals with procedure and front line A&E. All emergencies go to the public system and when a GP has needs help he goes to the public system

What would help and is already done is to farm out procedures. Things like specialists whom a lot work in both the public and private system. Just a matter of funding it. Instead of meaningless tax cuts and more four lane truck roads, spend the money on health.

Totally agree. Also, if patients in the private system have significant complications, they will ship them off to the public hospital to manage these. I’m assuming the tax payer picks up the bill

Private anything, cherry-picks. Including 'client' wealth.

We are a wider society than that - not that some acknowledge this. My initial comment holds, though; a sustainable way of living on this very finite planet, does not include current 'incomes' of doctors, lawyers, high academics...

Money is a claim on the planet - for processed parts thereof. It is keystroked into existence by a discipline who are only taught to back-cast. All the discussions we have from now on, are during a paradigm-change which renders back-casting moot. And perhaps our concept of 'private'.

We are all going to die. The sky is falling.

Broadly agree, however there is significant difference in incentives between public and private.

Private system in Nz is geared towards highly profitable elective procedures. Any complex or acute cases are sent to the public system. The private system is able to operate a model where people have a surgery, it’s straightforward(ish), they stay in hospital for a few days and all goes well.

The public system can’t really operate this model because it’s dealing with many more unknowns and any serious complications from private system get sent to public. So the private system efficiency in NZ is a little bit ‘fudged’ if you will because it doesn’t bear the operational or financial costs when things don’t go to plan.

I still firmly believe that for most outpatient and elective things private is much preferred and NZ should be moving in this direction with a public/private system with subsidies or public insurance helping to fund the private arm.

Unfortunately acute care will always have to be public or we will need very expensive health insurance premiums as NZ doesn’t have the population to support a private tertiary system.

DrGrump, some observations........

ACC surgeries are by definition accidents or they do not qualify so not truly elective in many circumstances (fractures and so on). The private sector performs surgeries on a good number of "outsourced" DHB elective cases too. Neither of these are "highly profitable" and are remunerated below market rates. This also partly confounds the selection bias that means wealthier NZ'ers who can afford health insurance are the only recipients of health care in private facilities.

ACC is to an extent the public/private model you describe. Without it, the DHB's would be truly overwhelmed.

I’m sorry you are incorrect.

Acute fractures requiring surgery cannot be managed in private under ACC. I have years of experience working with ACC. ACC is fundamentally flawed and a sensible option for NZ would be to significantly revise it or replace it.

ACC and public outsourcing work is very profitable - Otherwise it wouldn’t be done.

I looked after a combined number of 7 wrist and ankle fractures in September at a private surgical facility. This is not unusual.

You need to consider your audience more. We are not as ill-informed as you may have hoped.

That’s interesting. Out of curiosity did you do the ORIF/acute surgery privately? Or were these secondary elective procedures. I have left NZ now but in recent memory have not seen acute trauma surgery been done privately and understood this was not legally possible. Very happy to be corrected.

Your personal comment regarding the audience of the platform is confusing. I hope for the audience to be well informed.

FYI I believe that a well developed private system is the only viable way forward. Not hating on the private system or the work that you do. I work in public and private.

I also politely suggest you look up the definition of ‘elective surgery/procedure’. You will find that accidents and non acute trauma surgeries that are performed privately under ACC in NZ are almost certainly defined as elective or semi elective procedures.

I am very happy to stand corrected if you can prove otherwise.

Correct in the private surgeries but they have the Public Health Acute Services Agreement so acute surgery is still done under public but bulk invoiced annually to ACC by my understanding.

Yea you are correct. It still uses the public service but funding stream is different.

You might want to check out the difference in complication rates between the public and private sectors....and where you end up if something goes wrong in a private hospital

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33402263/

Then there's the surgeons getting their "freebies" ( registration, CME budget etc) from the public sector whilst mostly earning the cash from the private....

Wow, that's a seriously uninformed comment.

Surgical complications are unavoidable. When they occur they are usually financially covered by ACC as a treatment injury and the DHB can claim those costs back. The decision to move patients is not taken lightly and is based on their needs and where they are best met. I can assure you none of those patients would have expected or wanted a complication. Most procedures carried out in private facilities are also procedures that do not need to be financed by the public purse in the first place (colonoscopies, joint replacements, hernias, tonsils, grommets, and so on) that would certainly qualify. There is an argument that because of this health insurance premiums could be a valuable target to offer tax relief rather than vilifying those unfortunate enough to get a surgical complication and need urgent assistance.

As for CME, medical registrations, and so forth. These are compensated (CME has a maximum amount per annum) commensurate with FTE. If you work 0.7 then you receive 70% of the costs. These are contractual requirements dictated to employees on PAYE who cannot tax offset them - hardly a "freebie".

We don't have private EDs, and private hospitals can maintain efficiency by never having to do anything they didn't plan on. They do surgeries scheduled weeks to months ahead, with surgeons and specialists they know will be available. The public system often has to do a surgery on someone who showed up in an ambulance and needs it today, and that surgery will bump an elective that was scheduled for the same theatre slot, causing a knock-on delay to potentially tens of other surgeries. That simply doesn't happen in private.

I had a cancer diagnosis a decade ago that was covered by private insurance, but the specialist (private) referred me back to herself in the public system for the surgery because she couldn't bump anyone on her private waitlist to operate soon enough. It was still a 2 month wait in the public system, but it was going to be 4 in the private system. The private system simply can't (and doesn't want to) react to acute needs.

White Cross is a good example of a private ED.

White cross is not a private ED. It is an urgent care.

Perhaps these points make sense to an economist without a background in healthcare. As someone with a background in both medicine and economics/finance I find it to be rather naive.

I have left in NZ in the last 2 years and work in Aus as a Dr now. It is already unlikely I will return to NZ in the near term as the health system is so dysfunctional. One thing NZ should not be doing is copying the NHS in any way.

All health care for everyone should be free, accessible, timely, and comprehensive.

Now, it is none of those for people without health insurance.

New Zealand needs to make the first $40 or so of everyone's income tax a ring-fenced Medicare levy to replace all private medical insurance with universal insurance. The Medicare levy needs to be enough to finance primary health care and hospital care and surgery. Whether that is delivered through a state health service or private health services is of little interest to the patient, who simply wants free, accessible, timely, and comprehensive health care.

"The ED crowding we hear so much about is largely due to flow issues later in the care continuum. A key aspect of this is patients staying in inpatient beds longer than necessary"

But the author offers no evidence for this. Why? I suspect that it fits his right wing, neo-con bias. How about there being a lack of staff and a lack of beds? because that would mean more resources-money-being pumped into the system. We can see this clearly demonstrated in the government's thinking on the much-needed new Dunedin hospital. They have invented-in other words, made up(lied) a 'cost blow-out to justify cutting it back. So, in say 10 years, we will see that it is inadequate to properly service an ever ageing population's needs.

Exponential population growth, who would have thunked that the infrastructure would't keep up?

I feel like a lot of this is well articulated apart from:

For long-term sustainability, health investment should focus on short-term workforce productivity...

It then goes on to talk about addressing medical ailments. If we consider that good health is the objective, then in this context improved health would be a result of workforce, processes, partnerships with the patient & whanau for healing, scientific knowledge as well as the use of quality tools in suitable environments. To just talk about workforce productivity is misleading framing.

By oversimplifying health into factory thinking and concepts of production / procedures per FTE, the framing disempowers all humans who could be of assistance, and their ability to contribute to their own health in positive ways that might be much more effective tham medical interventions.

Same applies if the objective is for maximally positive net contribution by each person to society as holistic health is an enabler of that.

Empowering people and their supporters to take the steps required to stay, get and become healthy with education, lifestyle choice and public systems only playing a supporting role is the best value for money.

... But that doesn't increase GDP anywhere near as much as pointing the finger at the health workforce and demanding unnecessary productivity and unlimited choice

But makepeace: There is massive workforce non productivity. Not everywhere but it exists indeed.

Example. Just an example. Referral systems. Multiple history taking of the same history. User divided up between non cooperating specialities.

There is a lot to learn from factories.

I was arguing for addressing systemic issues without oversimplifying or framing with restrictive language too early.

Yes, there's inefficiencies in some areas. You seem like an intelligent any person.

with the breadth and rate of change of different parts of the healthcare sector and its privacy and other regulations, how much $ do you think it would cost to solve the digital health records problem?

Do you think that someone hasn't looked at that problem, priced it up and proposed a solution?

The fact that there's no unified referral system is a choice. A choice probably would have been made to allocate budget to address other problems, and live with a bit of inefficiency in one area whilst something is done elsewhere

Heck while we're at it, increased access to medicines does not necessarily equate to better health outcomes.

Prevention of ill health by addressing the social, environmental and commercial determinants of health plays a much larger role in health outcomes of individuals than bottom-of-the-cliff medicines at the margins for the already-sick

As they say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

A couple of good comments above makechange. We seem to have a plethora of articles that fail to step back far enough from the problem they're trying to solve.

Where was the discussion about our terrible diets leading to massive demand of health services in the first place or the analysis of why healthcare workers ask for higher wages (the largest cost increase has been the cost of land which again has been entirely self-inflicted)?

They need serious social media advertising about the dangers of uncontrolled diabetes. The level of peripheral neuropathy and amputations due to infected toes and feet will only continue an the cost for that is sizeable for the rehab, prosthetic limbs etc.

100%

Simplistic explanations for outcomes of complex systems sounds good, but they fail the "does the real world actually work like the article describes it?" sniff test.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.