By Andrew Coleman*

In 1974, the Labour government led by Norman Kirk introduced a compulsory saving scheme. Two years later it was scrapped and replaced by an early version of the current retirement scheme, National Superannuation. As a result of this decision, New Zealand now has the most unusual retirement income and tax policies in the OECD.

If these policies were better than those used in other countries, this would be fine. But this might not be the case. Despite some very good features, our policies have three major problems. They impose high costs on current and future generations of young people, who are required to pay much more in taxes than is necessary to provide the pensions they will receive. They mean New Zealand relies on some inefficient taxes that artificially distort investment decisions and inflate property prices. And they exacerbate some dimensions of inequality.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the compulsory saving scheme, this series of articles re-examines whether New Zealand’s retirement income policies are suited to the 21st century. If not, it may be time to redesign aspects of the system, particularly for those younger New Zealanders who have inherited policies they had no role in creating. We will begin by looking at the history of retirement income systems in New Zealand and around the world.

Mandatory retirement income schemes come in two main types. The first type is a social insurance or contributory system, which includes compulsory saving schemes. These schemes are designed to help people save for their own retirements by making them put money aside when they are young and middle-aged. Contributory schemes are funded from special social security taxes on wages and salaries, while compulsory saving schemes are funded by placing a fraction of a person’s wages or salaries into a personal saving account. The government keeps track of each person’s contributions and bases their pension on this total. Since these schemes are designed to help people save, people who make larger contributions get larger pensions when they are old.

The second type is a welfare system. These retirement income schemes are designed to provide older people with a minimum income level to keep them out of poverty. They are funded out of general tax revenues and the size of the pension people receive is unrelated to their tax payments. Welfare pensions can be universal, so everyone gets the same pension, or they can be means-tested. If they are means-tested high-income or wealthy people receive a smaller amount, or even nothing.

In addition to these mandatory schemes, many governments also have voluntary saving schemes like KiwiSaver, designed to make it easier for people to save for their old age, but without compulsion.

The first contributary scheme was introduced in Germany in 1889, and the first welfare scheme was introduced in Denmark in 1891. Other countries followed suit, typically with one system or the other. These systems evolved over time as the advantages and disadvantages of both types of systems became apparent. They also became much larger in the 1950s and 1960s as life expectancy increased. By the end of the 1960s, most developed countries adopted a hybrid system based on (i) a contributory or social insurance model to help people save for retirement and (ii) a welfare model to ensure low-income people have adequate income when they retire. New Zealand is quite different to the rest of the world because it only has a universal welfare-based pension scheme.

New Zealand created a welfare-based government pension plan in 1898, funded out of general tax revenues. These pensions were available to most people over 65 of “good moral character” who had spent at least 25 years in New Zealand, although they were not initially available to Chinese immigrants. The pension was small, £18 per year (or about $4300 today) when average wages were £75 per year for men, and £30 for women. It was stringently income- and asset-tested. People who earned more than £34 had their pension reduced one-for-one when they earned extra money, so anyone earning over £52 received nothing. The aim was to give money to people who had no other means of support, rather than to help people save for their old age.

The “Age Benefit” pension was modified between 1898 and 1938 by increasing its size, by reducing the eligibility age for women to 60, and by including Chinese New Zealanders. But it was still designed to provide welfare for low-income people and the means-test remained central.

Several changes were made in 1938 by the Labour government headed by Michael Savage. The rate was increased, the age for the means-tested “Age Benefit” pension was reduced to 60 for men as well as women and a second “contributory” pension was introduced for people over 65. This “contributory” pension was the same for everyone, and while it was initially much smaller than the “Age Benefit” pension, it was meant to increase over time until it was the same amount. The new over-65 pension was funded by a social security tax on wages and salaries and was not means-tested. This was an unusual scheme because people paid social security taxes but the amount of the “contributory” pension they received did not depend on the taxes they paid. The contributory pension steadily increased in the 1950s as planned but the separate Social Security tax was abolished in 1958 and payments were funded from general tax revenues.

There were two major changes in the 1970s. A Labour government introduced a proper compulsory contribution scheme in 1974, in conjunction with the existing pension scheme. The contributions were 8% of income, paid for by employees and employers. This was a true contributory scheme as the payments were only levied on labour income and the size of an individual’s pension depended on the size of their contributions. This is broadly consistent with what was happening in other countries where the pension systems were converging to a mixed welfare and contributory scheme.

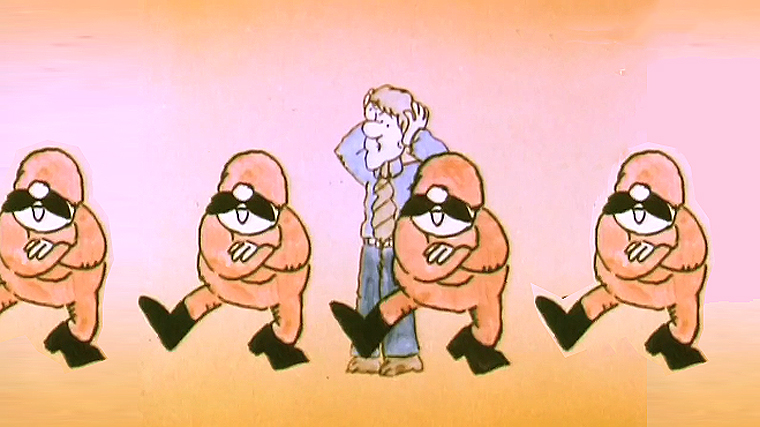

It did not last. In the 1975 election, the National Party led by Robert Muldoon campaigned to abolish the compulsory saving scheme and replace it by a universal, flat-rate pension. The campaign featured New Zealand’s most influential advertising effort ever, featuring the infamous dancing Cossacks. After a landslide victory, the new scheme, National Superannuation, was introduced in 1977. The pension for a couple was increased to 80% of the average wage and made available to everyone over 60. But taxes were not increased, so New Zealand started running large government deficits and the national saving rate dropped sharply.

It soon became obvious that the scheme could not persist without higher taxes. Successive governments cut back the scheme by decreasing the pension and by imposing surcharges to reduce payments for higher income people. These changes became increasingly complicated, and the surcharges were abolished in 1988. More changes followed in the early 1990s. The pension age was gradually increased to 65, and strict means-tests were imposed. Many of these changes caused considerable political backlash, and means-testing was abolished.

In 1997 a referendum was held, giving voters the option to choose a compulsory retirement scheme like the one Australia had just introduced. It was rejected by over 90% of voters and that was that. It meant New Zealand entered the 21st century with a retirement income scheme almost identical to the 1977 scheme, although less generous: a universal pension provided to all New Zealanders over 65 who satisfy eligibility criteria, funded from general tax revenues.

Since 2000 there have been two new features. The New Zealand Superannuation Fund was established in 2001 to finance some of the expected future costs of New Zealand Superannuation. The Fund allows the government to “bank” additional tax revenues to pay part of the future pension bill. The Fund was over $60 billion by the end of 2023, in part due to excellent investment returns.

In 2007 a voluntary saving scheme, KiwiSaver, was introduced to help people save by getting them to regularly place a small proportion of their wages into a saving account that, with a few exceptions, cannot be accessed until 65. It does not affect a person’s entitlement to the government pension.

All this means New Zealand started the 21st century much as it started the 20th century – with a non-contributory retirement income system funded from general taxes rather than social security taxes. The current system is much more generous and it is no longer means-tested. But it is still fundamentally a welfare programme not a saving system and this means it is very different to the retirement income systems in other OECD countries. It is what older New Zealanders asked for when they voted to get rid of the contributory scheme in 1975, and when they rejected a compulsory savings scheme in 1997. However, it may not be what New Zealanders under 45 want, for they have never been asked.

New Zealand Superannuation has several attractive features. It also has several serious downsides and these disproportionately affect younger people. The next few articles look at these downsides, to see why a pension scheme based on a mixture of contributory and welfare principles may be more attractive to young people than the scheme they have inherited.

*This series and an accompanying paper are based on work I started in 2020 with Jeanne-Marie Bonnet while we were both at the University of Otago. I am very grateful for her assistance and insights. All errors remain my own. (This article is part 2 in the series. Part 1 is here).

**Andrew Coleman is a visiting professor at the Asia School of Business. This article is his personal view of retirement policy in New Zealand, based on academic study.

Coleman is on extended leave from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, while working overseas. The views expressed in this article do not represent the RBNZ and are unrelated to work conducted at the Bank, which has no responsibility for retirement policy in New Zealand.

73 Comments

The second type is a welfare system. These retirement income schemes are designed to provide older people with a minimum income level to keep them out of poverty. They are funded out of general tax revenues and the size of the pension people receive is unrelated to their tax payments.

Many entitled old people would strongly beg to differ. Also, if it's "designed to provide older people with a minimum income level to keep them out of poverty" then why do we hand it out to millionaires and those still in work earning over $100k p.a.?

Dan, why would "many entitled old people" beg to differ? You don't explain that comment.

And to your second point, that is exactly what AC is trying to explain.

The questioning of 'universal' is valid.

But other than that, AC explains nothing.

He starts (it seems - certainly not qualified) assumption that money is a store of wealth. Hence the assumed validity of 'savings'. And I'm sure he thinks of 'investment' in the same manner - they all do.

Money, however, is just proxy. For as you know, the reducing stock of low-entropy energy, and materials/resources.

I gave him a list of references, last time. We wait.

Different topic PDK. He's working within the system here rather than working on avoiding a societal and environmental collapse. Both processes are needed, this one is largely, but not wholly, based in a level of denial.

Interesting. So, if we both have nothing, and I find a 100 dollar bill. Who has more money, and who has the store of wealth ? I think my 100 dollar bill is a store of wealth at that point and trumps your zero.

Silly comment.

Time is missing from your little anecdote.

As it is from the Coleman posit, in longer form.

Sigh

We can call it a store of wealth, a proxy, or a voucher.

They depreciate, usually, but they're still indicative of a value.

That was on the up-side of growth - when there was still physical underwrite for the exponentially-more proxy being keystroked into existence.

We are entering the downside.

The past is therefore invalid.

There's still physical activity that underpins the value of money.

I can't argue the direction that value will likely take, but it does represent a store of value.

'Many entitled old people' become indignant when told they are social welfare beneficiaries and insist 'I earned it', despite the clear wording of the Superannuation Act that the sole qualification is years lived in New Zealand, with having worked or paid taxes irrelevant.

Millionaires get it because millionaires are noisy: \Winston Peters's NZ First and Grey Power put an end to the surcharge on those with other incomes, rendering NZ Super unaffordable.

As the first $ of income is taxed and you cannot live without income everyone is a taxpayers to contributes to pensions. The issue is a declining number of taxpayers per pensioner.

"...why do we hand it out to millionaires and those still in work earning over $100k p.a.? "

You meant to say "why do we hand it out to the diminishing number of net income taxpayer people funding Super for more than half of NZ households."

Because it's welfare not a loyalty scheme? I'm one of these households that pays a significant amount of income tax, and would rather see it handed out based on need not greed.

I don't begrudge hard working households that get most of their tax back in the form of tax credits, we've had a generation of Boomers with severely limited cognitive abilities (a side effect of childhood exposure to lead products) in charge of screwing the economy. First in 1987 with the stock market crash, and now the housing market starting off as the biggest wealth transfer in history which is looking like it'll drag the country down with it.

Something as simple as raising a family has become nigh on impossible for lower to middle class, a side effect of needing 1 income to pay for the roof.

If you think the generations coming through are going to be smarter and more adept at problem solving, I have a glass aromatherapy pipe to sell you.

Yes, I think they will grow up to be smarter and more adept at problem solving. The generations that followed the Boomers most certainly have been.

They might lack common sense but they're kids. Like kids at every generation, they'll have their quirks/juvenile mindsets and lack of common sense. It's just old people like to pretend they had today's wisdom at 12 years old. Which is ironic, because many old people demonstrably lack the common sense they all claim to possess.

1960s approach to housing shortage: devise the quickest, fastest, most cost effective way to deliver as many houses as needed. Boom, done.

2020s approach to housing shortage: people without housing shouldn't have to feel like they're in state housing. Public housing should be bespoke, mirroring that of the private market. Slowly trickle feed expensive new houses, whilst also having more vacant government houses than the market at large, because they don't meet your self imposed standards, despite people having lived in them for 60 years prior.

I'm not so convinced. I think priorities have strayed so far from basic fundamentals we'll eat ourselves.

24% of working kiwis are over 65 some of necessity others like me of choice and the fact we are still employed proves we still have a value that other Kiwis value enough to employ or buy from. A Gen Z balled me up saying us boomers just don't understand how much they have to understand or put with - I Phones/E-Mails/I Pads/Tik Tok etc which us Bookers didn;' have at their age - I replied you are right we were busy inventing and creating those thing s for you.

Well done on the half assed generational "points scoring". Rooted the economy/housing market, but can ramble on half a dozen "tech" items and try to appropriate them as a single generation's accomplishments. I'm sure Steve Jobs couldn't have done it without you.

Did you say "Gotchya" to this Gen Z, all with a smug look on your face? Did you tell them how you replaced all paper/glass packaging with plastics too?

What's the point of squirrelling funds for your retirement if the govt is going to deny you a pension for working hard and being a good saver?

What's the point of working if the Government is going to pay you an unemployment benefit?

It is interesting when one considers the culture of the times. Today information technology rules. officially i am an old fart, but I also have an IT degree. Today what politicians tell you can be thoroughly tested and investigated by searching on line. It is very easy today to get other opinions, facts and data to help you make choices (when you're not blinded by ideology). But what AC presents here would result in many later generations turn around and say "See it was the Boomers. They all screwed us!" The reality though is much different. When all those things AC has stated occurred the only source of information was a local newspaper and maybe a library. Strictly hard copy! People from all walks of life simply had to trust the 'system'. Politicians were respected just like Doctors and lawyers and Judges. No one seemed to understand that they really were fallible human beings too. But people always believed what they were told by those people. History today tells us that what we were told was not always true, or wholly true, or complete. And so we get to what AC is telling us.

His question after all is how do we provide for all without creating injustice?

'See it was the Boomers. They all screwed us'

But we DID, Murray. Some did it unwittingly. Some did it selfishly. Economists did via faith/belief. And some of us tried not to disadvantage future generations, by buying as little as possible (kind of excludes Professor incomes - they are of the higher-end of resource-consumers NOW, at the expense of those they teach), and a whole lot of other actions. Inevitably, commercialization of the Commons - which was essentially the right to do stuff yourself - has closed down those 'other actions', though.

The young aren't allowed to build their own house, and will find it increasingly difficult to harvest water of grow food. Those will be restricted, sold/owned and rented. We did that whole transformation in a 70-year period - a short blip in human terms. It was a once-off. You and I timed it perfectly; a near-full planet, the right timing in knowledge terms. It cannot happen again.

They are being handed the dregs, and the entropy (pollution, including CC). And they increasingly know they're part of an overshot population - which is why they're not procreating. Of course they'll be pi--ed. And Andrew's pile of proxy? I can guess where they'll tell him to shove it...

Frustration with ideology aside, we do need to discuss what we leave future generations - but it's what we leave them in terms of a physical planet, and ecological life-supporting parameters. Proxy schmoxy.

I understand what you're trying to say, but you will fail. What you're trying to say is that every living thing squanders resources at the expense of the next generations. For what ever reasons, until the dawn of the informaton age, people had very little if any way, most none at all, of understanding the bigger picture. Those in power BS'd everyone to preserve their own positions. To argue that everyone of prior generations is culpable is like trying to pin the sins of the fathers on to their sons.

As for most of my arguments, here I will tell you now to look to the politicians and those in power, because the rest had little if any choice.

No. I'm not.

That all species are dissipative, is true. But we levered fossil energy to be more dissipative than any real-time species - including our own up until the FF spree - could ever be.

It was a one-off event - and had nothing to do with information. All to do with energy use, rates thereof.

I think I get you. You might find some solace in understanding that the ‘boomer’ hatred is in large part due to many of the boomer generation that have overinflated egos and entitlement towards everything. They talk to us today as thought if they were in our shoes they’d be doing far better than us, it is patronising to the highest degree. They do this because at our age they were doing better, but in their heads they can’t accept that their rewards in life weren’t entirely their own making, that they benefitted from the pillaging of our social contract.

SKF

What 'social contract'? What a load of bollocks.

Is the 'social contract' where the government squanders billions of dollars on publicly owned companies like the airlines, buses and railways?

A few weeks back, I was speaking to my mum about declining birth rates. She reckoned when she was at school in the 70s, the occupation of every students mum was "housewife". Wonder what it's like today, and how that impacts future parenting aspirations.

In the early 70s, the life expectancy of a male was 68. Now it's 80.

A pay as you go system, like super, and the rest of our tax-benefit system is the easiest way to go about it. Predicting future demographics is another matter entirely. So, we have the situation we have today.

Blaming someone else is super easy, and relinquishes the burden of responsibility from the finger waver. Tough calls lie ahead.

Agreed totally.

It is a real bind.

Ballooning aged costs.

A need to change provisioning for future people's retirements.

Escalating maintenance and development costs for infrastructure.

High debt, with no easy route towards generating and retaining new profitable export industry.

My intuition has me thinking we'll avoid seriously addressing this, well past the point of salvation, because it's more politically prudent to continue to sell more popular policy.

We can find savings by trying to scrap lunches for kids in schools and not funding cancer drugs, all to ensure we can avoid the difficult conversation with the most wealthy and entitled generation to ever live about whether they need full taxpayer funded welfare payments.

You can keep hammering on about boomers, but that doesn't detract from the grim realities that the level of public services enjoyed over recent decades will be even less sustainable after the boomers have gone.

"... it's more politically prudent to continue to sell more popular policy." Like tax 'cuts'

Yep. The reality is we either need big tax increases, greatly reduced services, or probably both.

Who's keen?

In the 70's you didn't need one full modest income just to pay for the roof. You could raise a family of 4 - 5 kids on a single laborers income. Hell, my father raised 2 kids while mum was at home in the 80's/90's working in a fishery stacking crates and paying off a mortgage.

Good point on the life expectancy, it's specifically 82 currently. The average pensioner will spend 17 years on the pension. @ $20k p.a. each (ignoring inflation), that's $340k. Median income is $66k. Paye = $12k. So the first 28 years of a median income earner's entire PAYE covers the Pension...

Worse, somehow back when it was predominately single income households, they claim to have funded Super for 2 adults?

In the 70's you didn't need one full modest income just to pay for the roof.

The income was relatively higher, because your labour force was effectively half. Although coincidentally, there's estimates that 40% of the workforce is doing nothing jobs.

Worse, somehow back when it was predominately single income households, they claim to have funded Super for 2 adults?

It's not uncommon now to have 3 generations of dependents for 1 worker (kids, parents and grandparents).

Few if any factored any of this in. Seemingly obvious in hindsight, but even in the 2000s there wasn't much said about the falling birth rates.

A low productivity issue?

And doesn't an aging population mean reduced costs of youngsters in education and health. What is the net result of decreased costs of support for fewer children v increased cost of support for more aged?

Friend pulled the pin the other day. Compliments of National Super, Govt super and her part cleaning job she is earning well over six figures. And that excludes her investment income (cashed out Auck rental). Plenty of oldies on two schemes (or more) doing as well.

Don't tell the kids.

Good for her, I'd bet she paid net income taxes to support her own Super as well as the more than half of NZ households who don't pay net income tax.

She was a very modest earner, so the taxes she paid most likely contributed to her share of running NZ inc at the time...and no more.

That said, I''m not saying she is deserving or not, just highlighting how some of our retired are retiring on our old 'strong' financial economy...not the present shipwreck!

Is super only funded from income tax?

Super is worth something like $600-700k for a male at 65 (more for a female), you'd have to pay a hell of a lot of tax to fund that as well as everything else society provides.

Considering the amount of wealth that is about to be passed from the Boomers to the Millennials, I think its about time we had inheritance taxes (and accompanying trust busting and gift taxes to prevent tax evasion). The amount of tax should be directly proportional to the amount of the pension you received. If you die before 65 then you pay no inheritance tax, if you die at 90 your entire estate goes to the Govt to pay back the 25 years of welfare you just received. Those that can afford to be self funded can opt to not receive a pension and thus avoid inheritance taxes (and any need for complicated tax evasion measures). Need both the carrot and the stick.

Nah you don't have to worry about that KW. Research has indicated that inherited wealth lasts at the most three generations, and the rich little snots and their sense of entitlement squanders it all. Spread across business and taxes it gets recycled anyway. Inheritance tax just gives it to politicians to waste.

The proposal above did not mention limiting inequality. It was pitched as a way to pay for the current superannuation bill.

We've already had inheritance and death taxes in NZ and they cost more to administer than they collected.

So the govt. canned them. I earned it, it's mine and I'll do whatever I want with that money.

The rules are very easy to understand and work well. It basically goes like this.

i) Everyone will get the same state funded pension, until it is wound down and compulsory schemes take over (30 years away at least - if ever).

ii) If you want in live in poverty. Don't pay off your debt during your working life, and rely on the pension that everyone gets. Sadly lots of people do this.

iii) If you want to just scape by in retirement, pay off debts before finishing work, have a buffer, and collect the pension that everybody gets.

iv) If you want have a fantastic retirement, take responsibility for your own actions, pay off debt, live within your means, save and invest. The pension that everybody gets is then used as play money or for whatever you choose. Few people achieve this.

If the state funded pension is going to go away, it will not be going away any time soon, it may slowly disappear over decades and will not become means tested (that would be political suicide so no-one will attempt it). Retirees regardless of how wealthy they are, will apply for the state pension regardless of how anyone feels about it. That choice is theirs and theirs alone, no matter how much people dislike it. So, the choices for everyone are basically the four choices above. If you want to have option iv), you need to decide early though or get lucky.

Couldn't have said it better. Bang on.

Reality is this should be taught in school. People become full of anger and envy when they have 10 years to retirement and they finally realize what is coming (and what the state pension actually means).

'save and invest'

I was with you until there - I think we need to think of that in physical terms. Just as budgeting for the likes of a Local Authority should be the physical-earmarking of piles of stuff needed to maintain whatever, for at least it's expected life. We got by, while there was a relatively untapped planet, budgeting in proxy (at all levels, including private). That era is leaving us - and the High Priests of the era are becoming increasingly irrelevant.

Put it another way - our current accounting system is no longer fit for purpose.

I would be interested to see numbers around what sort of abatement rate, similar to other benefits like WFF would be required to make the current system affordable? Maybe 15-20%?

It is bizarre to me that our main children's benefit (WFF) abates at a rate of 27%, but the one for old people doesn't abate at all. Why do we invest so much more in our older people than our future generations?

People say it would be political suicide, but surely it could be sold on an equity ground, particular if a student loan style threshold of say 20k/year applied before the abatement kicks in.

Agree on this one and I am within 10 years of retirement.

Though, within 25 years the majority of boomers will be pushing up daisies, so that will ease the system.

The biggest problem then will declining populations world wide.

We are only maintaining our current population with help from the developing and 3rd world.

Handy then we have such a small starting base and billions of potential new New Zealanders.

"Though, within 25 years". Oh, that's good, not a long term issue then?

'It is bizarre to me that our main children's benefit (WFF) abates at a rate of 27%, but the one for old people doesn't abate at all. Why do we invest so much more in our older people than our future generations?'

A surtax on other income kept NZ Super affordable. But retired people are enthusiastic voters, and the wealthier they are the more enthusiastically they vote. The surcharge on other income was abolished in 1998, guaranteeing that NZ Super would go untrimmed to those who don't need it, and ultimately become unaffordable.

https://www.goodreturns.co.nz/article/891752323/the-removal-of-the-surc…

'I would be interested to see numbers around what sort of abatement rate, similar to other benefits like WFF would be required to make the current system affordable? Maybe 15-20%?'

Susan St John and Claire Dale have proposed putting all who sign up for NZ Super on a separate income-tax regime that would effectively claw back extra income at a higher-than-usual tax rate, helping to maintain the affordability of NZ Super for those who need it, keeping it universal, but clipping the wings of those who have less need of it.

https://www.auckland.ac.nz/assets/business/about/our-research/research-…

Hello

Thanks for your interest.

As you point out, Susan St John undertakes various comparisons of how a surcharge or abatement option could help reduce the size of the pension bill in the future. However, to some extent this is answering the wrong question. Indeed, it is really offering a solution without considering all dimensions of the problem. Even if there were a surcharge that reduced the total amount paid out in pensions each year, so long as we continue the same way of funding NZ Super then as a country we shall be imposing much higher costs on young generations than are necessary to fund their own pensions, we shall be using taxes that artificially inflate property prices, and we will have a system that still exacerbates some dimensions of inequality. The question is whether these problems can be solved, and if so what is the best combination of methods that can be used to solve these problems. A means test could be one part of the solution - although survey evidence suggests it would be a very unpopular part of the solution. But there may be other ways to solve these problems. One of the reasons I keep emphasising that New Zealand has such unusual retirement and tax policies is to open the possibility that the solutions used in other countries may be more appropriate. More importantly, they may appear much more desirable to younger generations who will spend all of their adult lives in the 21st century than they appeared to the generations who came before them.

AC

Absolutely false equivalence to suggest that super is resulting in using/requiring taxes that artificially inflate property prices.

I agree that a problem with Susan St John's surtax proposal is that it doesn't address the funding of NZ Super from current taxation, a problem that increases as the elderly beneficiary population grows and the income-tax-paying workforce proportionately declines.

Perhaps the answer to this is to greatly increase investment in the NZ Superannuation Fund, funding it not from income tax, but by the introduction of capital gains taxes, and the reimposition of land taxes, inheritance taxes, and gift taxes.

Thanks, unfortunately it appears to exclude PIE income, where WFF abatement includes that, but even without it it appears that a 10% rate would reduce the cost of super by about 10%, or 1.5 billion per year. That's significant.

I'm not a big fan of Susan St John's idea, I think an abatement in the same was as we already do for WFF or other benefits is understandable, easy to calculate with an online calculator and one fewer special case in the system.

I strongly believe that NZ Super, a social welfare benefit, should go those who need it, not to those who don't. I'm agnostic on whether the withholding from those who don't need it should be by surtax or by abatement.

What's the point in saving for retirement if you won't get govt superannuation? May as well spend it on a good car, a few holidays, high living and let the govt fund retirement.

Susan St. John is a socialist hell-bent on looting the bank accounts of those that save, work and make smart decisions.

An interesting aspect of NZ Super in NZ, a country needing migration in both directions:

If a NZ Super pensioner has previously worked some time overseas, that overseas part pension is fully deducted from NZ Super.

In other words, NZ expects that overseas part pensions are portable and drawn here. Fair enough I would say.

In contrast, for those who worked in NZ and then move overseas before pension age, different rules apply: No part pensions, no portability.

In other words: When leaving NZ before 65, all the years worked in NZ will turn into a part pension gap.

It's just something to bear in mind for the mobile workforce: NZ takes, but won't give. Quite unique.

That's because NZ Super is simply a social welfare benefit to ensure that the old folk don't end their days begging in Queen Street or Lambton Quay. It was intended for people who live in New Zealand (or realm territories), not for those who want to retire to Phuket (though that has since been modified).

My info is more for those who leave NZ well before reaching retirement age. If a NZer leaves NZ at age 35 for example, they will have a 15 year contribution gap in most countries.

True. But NZ Super is a social welfare benefit scheme, not a private superannuation savings fund. It would seem a big ask to redesign the entire fund to provide for those who might decide to skip the country and live elsewhere.

Until recently NZ Super was available in full to anyone who had lived 10 years in New Zealand over the age of 20, of which 5 had to be before the age of 60 (I think), and be living in NZ when they applied for their Super. I think the 10 years has now been changed to a 20-year minimum to punish the elderly parents of immigrants who decide to live here, and applies to everyone. (It would be a bit obvious to make an exception for people born here who then left for a few decades then rolled in again at 55.)

I think the superannuation surcharge was abolished not in 1988 but in 1998, three years before the Superannuation Act established NZ Super in more or less its present form.

https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2007-11/prg-msd-dnzcri…

Yes, there were all sorts of changes in the 1980s and 1990s, all described by different names. The key point is that in the 1980s various ways of reducing payments to higher income people were introduced and by 1998 all means tests or surcharges were removed. Consequently the pension scheme looked very similar to the National Superannuation scheme introduced in 1997 - except entitlement started at age 65 not 60, and the amount for a couple was roughly 65% of the average wage, not 80%.

A very good outline of the period is by David Preston

https://assets.retirement.govt.nz/public/Uploads/Retirement-Income-Poli…

I remember all the 70s superannuation stuff being discussed as a teenager & I remember thinking quite clearly "So we workers are paying for the Olds to retire today." Then I remembered that they had been through a war & a depression so I forgave them. Life moves on.

Several major jumps from apparent correlation to causation in this article, plus completely ignoring equity.

We have an inconsistent tax regime - eg lack of capital gains and inheritance taxes, limited resource use taxes, income tax not progressive enough. However, the author cites our pension system as somehow causing that inconsistency.

Then there is the failure to recognise that money and taxes in a sovereign currency issuing country is different to the misleading and false neoclassical theory.

And in the emphasis on contributory pension schemes largely ignores the fact that a fair % of the population are not in paid employment, or that we are a low wage economy, with increasing wealth inequality.

And the comparative efficiencies and costs of universal payments coupled with progressive income tax v means test (of assets).

Maybe later articles will pick these points up? And seriously assess the option of continuing universal super coupled with a more progressive income tax if you receive super.

Hello, AR5886

Yes, this series will look at some aspects of equity, and it will look at many aspects of taxation. There is now a large literature that demonstrates how poorly designed income taxes can artificially inflate house prices by increasing the amount people will pay for well located properties or large houses (in part because alternative investments are highly taxed), and the New Zealand tax system has many of these faults. Many other countries have reduced these problems by modifying income taxes or adopting progressive expenditure taxes, or by adopting a capital gains tax. As the literature makes clear, and as many other countries do in practice, one part of the solution is to adopt social security taxes that are only applied to wages and salaries and other incomes, but not interest or dividends or rents or other capital incomes. Other parts involve changing the way that retirement savings schemes such as KiwiSaver are taxed. A capital gains tax is internationally acknowledged to be part of an efficient and equitable income tax system (and a long time ago I wrote and published the earliest technical papers investigating the efficiency and distributional effects on housing markets of New Zealand's absence of a capital gains tax.) You might have to wait for the details, although if you search the web you can find the references to this large international literature in some of my earlier work (eg a 2019 paper on capital taxation available as a discussion paper from the University of Otago). Suffice it to say that many countries that have much more progressive tax systems than New Zealand do this; New Zealanders (especially young New Zealanders) should at least contemplate looking at their solutions to see if there is a way of improving our current system. There is no reason to believe that a system designed 50 years ago cannot be improved, and a lot of reasons to believe it can be improved.

Similarly, as I said in this article, almost all countries adopt contributory and welfare based pensions schemes. New Zealand is unusual because it doesn't have the contributory bit. You can keep the welfare components and add contributory components and ensure that people who have low incomes or participate little in the paid workforce still have a decent retirement income - indeed, a retirement income at the same level as received now. You can achieve desirable welfare outcomes without insisting everyone receives the same pension, and many countries do.

In that sense, over the course of these articles i hope to establish that it is possible to change the design and the funding mechanism of New Zealand's retirement income system in a manner that preserves its strengths and reduces its problems. It is possible to deliver similar levels of a pension at a lower long term cost and with less inequality, but we have not chosen methods to do this. But to work out whether it can be done, it is useful to understand the problems first and design solutions second, rather than simply offer a solution. Fortunately there is a lot that can be earned from the design of retirement income schemes and tax systems in other countries.

Of course, it may be the case New Zealand happened to develop the best possible system in the world back in 1977 and 1997. I personally don't believe this, and believe there are ways its best features can be kept and other aspects improved. But really, my beliefs don't matter, except perhaps for a belief that the younger people who had no role in designing the current system should be allowed to choose or redesign a system that is best suited to the way they want to live in the 21st century.

AC

Andrew reckons there isn't enough money for plumbers, school teachers or nurses to get super. Yet the RBNZ is increasing the number of PHD economists, an 18% increase to $105m P.A. in salaries in 2025. In 2021 low interest rates were the dominant narrative driving speculators to borrow more than they can afford so that the financial system is presently quite fragile, especially if house prices fall much further. Yet Andrew denies the obvious in his 2023 paper on the subject.

Maybe you could get a real job and make a contribution to society rather than wasting your time pissing on my leg and telling me it's raining.

Hello,

If you are going to comment, at least try and be accurate (and civil) in your comments. I clearly have not said that "Andrew reckons there isn't enough money for plumbers, school teachers or nurses to get super." or anything remotely close to this; the questions I am raising are largely whether there are better ways of providing retirement incomes to people. You will search in vain for statements that suggest I argue that people should have lower retirement incomes, as the series will demonstrate.

I am currently on leave from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, working at a university, and this series has nothing to do with the Reserve Bank. Incidentally, the 2023 Discussion Paper to which you refer clearly does discuss when it may be appropriate to raise interest rates to prevent periods in house prices temporarily increase and then fall. The whole paper concerns what happens to real estate and construction markets when demand for better quality housing increases following macroeconomic economic "shocks" such as income increases or reductions in interest rates. I know it is long - housing markets are complicated - but you may wish to read it again to better understand the position developed in that paper. For the record, the paper was written in 2021, when house prices and building costs were rapidly increasing, but only published at the beginning of 2023 as i was also teaching abroad for much of 2022.

AC

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.