By Andrew Coleman*

Fifty years ago this August, the Labour government passed the New Zealand Superannuation Act (1974) and introduced a contributory saving scheme. This scheme required people to pay 8% of their wages and salaries to the Government and in return offered them a pension based on the size of their contributions.

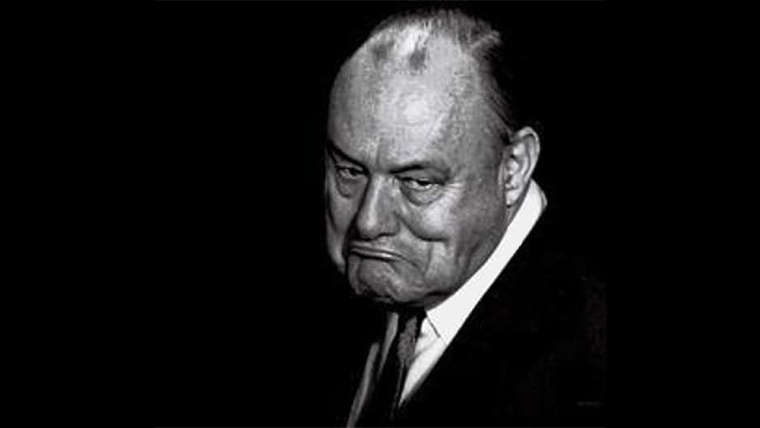

Between 1975 and 1977, the National Government led by Robert Muldoon revoked the Act and replaced it with a new universal retirement income scheme. After two decades of piecemeal reform by both major political parties, this scheme evolved into the current retirement income policy, New Zealand Superannuation. It provides a universal pension to all New Zealanders over 65 who satisfy eligibility criteria, funded from general tax revenues. Seen internationally, New Zealand Superannuation has one remarkable feature. It is fundamentally different from the schemes adopted in almost all other OECD countries.

Different, of course, does not mean bad. But while it has some very good features, the current structure of New Zealand Superannuation has three major downsides. Most importantly, it imposes very high costs on current and future generations of young people, who are required to pay much more in taxes than is necessary to provide the pensions they will receive. It means New Zealand eschews some of the most efficient taxes used around the world, but relies on taxes that artificially distort investment decisions and inflate property prices. And it exacerbates some dimensions of inequality. These are good reasons why none of the high income, low inequality countries of northern Europe have adopted the New Zealand model – and good reasons why the rapidly growing nations of the former Eastern European block have not copied it either.

A referendum held in 1997 overwhelmingly endorsed the new retirement income policy. Nonetheless, various governments since 2000 have expressed concern about the structure of New Zealand’s tax system and wondered about the future affordability of New Zealand Superannuation. In one major development, the New Zealand Superannuation Fund was established to change part of the funding of New Zealand superannuation from a pay-as-you-go-basis to a save-as-you-go basis. This step will reduce costs on future generations, although many New Zealanders, young and old, believe that more could be done.

Other aspects of the 1977 decisions have remained unchanged. In particular, New Zealanders fund current retirement income payments from general taxation, rather than social security taxes or contributions to compulsory savings plans that are used in most OECD countries.

The social security taxes that are used in most countries have two features: the taxes are used for specific purposes, primarily retirement incomes; and they are only applied to labour incomes. New Zealand uses a social security tax to fund contributions to the Accident Compensation Corporation, but it does not fund other social security payments in this manner. This is the single largest difference between the tax systems of New Zealand and almost all other OECD countries. Strangely, it is hardly ever discussed - neither the 2001 Tax Review, the 2010 Victoria University Tax Working Group, or the 2018 Tax Working Group devoted more than a page of discussion to the topic, despite its centrality to the tax systems of most OECD countries.

When Muldoon abolished the nascent contributory tax system introduced by the Labour Government in 1976, he cast a very long shadow over New Zealand’s subsequent tax system.

Its effects are not trivial: as a direct consequence of this choice, New Zealand has very high taxes on capital incomes and very low taxes on labour incomes relative to the rest of the OECD. These taxes artificially inflate house prices and delay the time it takes young people to afford their own homes.

Moreover, because there is no link between the taxes paid and the benefits received, the labour income taxes we use are more distortionary than the taxes used in other countries.

Over the next few weeks, I shall argue it is time for New Zealanders – or at least New Zealanders aged under 45 – to consider a fundamental restructure of New Zealand’s government retirement income system and its associated taxes. Why 45? – because nobody under 45 voted in the 1997 referendum that ensured New Zealand has the most unusual retirement system in the world.

These New Zealanders have spent and will spend their entire working lives in the 21st century, and it is my belief that they should be given the opportunity to decide on the types of taxes they pay, and the retirement incomes they receive, over the course of their adult lives. It should no longer be assumed that a tax and retirement system designed in the middle of the 20th century is suitable for the needs of people living in modern New Zealand.

Are there better ways to raise taxes and fund pensions? Many rich countries such as Norway, Sweden or Germany already collect more taxes than New Zealand – and they do it in ways which keep incomes high, and which generate less inequality than in New Zealand. These countries provide examples of tax system alternatives that are already tried and tested, and in many ways result in better outcomes than the New Zealand system. If young New Zealanders were to choose different types of taxes, they will not be sailing uncharted waters. Different methods of funding retirement incomes exist, and these may prove more appealing to young New Zealanders than the options chosen by their parents and grandparents.

The key requirement is the willingness to discuss the issue and find a solution. If New Zealand doesn’t do something sooner, it will have to do something bigger at a later date. If these discussions are not held now, and current pension entitlements are maintained, young people will face higher and higher taxes.

Young people might choose to pay higher taxes in the future to maintain current pension payments – or they could choose to reduce the pensions older people receive, or leave to countries where the balance between taxes paid and benefits received is more favourable. None of these possibilities are very attractive.

There are many different possibilities for reform. I shall suggest one, modelled on a scheme proposed a decade ago by the Financial Services Council. It combines a compulsory saving scheme with New Zealand Superannuation, like Australia, but with a twist that learns from the Australian experience. New Zealand Superannuation would be retained unchanged for people over 45. Of course, younger New Zealanders might want something completely different – or want no change. That should be up to them, albeit in conjunction with older citizens. Indeed, the purpose of the series is to explore some of the reasons why fundamental reform of New Zealand Superannuation may be desirable, not to argue for any particular replacement.

The international literatures examining retirement income systems and tax policies are simply enormous. This series of articles does not pretend to summarise them. Rather, its purpose is to reflect on of the ways New Zealand’s retirement and tax systems differ from those used in most countries; to discuss some of the social and economic consequences of these choices; and to analyse whether it might be possible to reform the current system to reduce its weaknesses while preserving its strengths. I hope you enjoy them.

*This series and an accompanying paper are based on work I started in 2020 with Jeanne-Marie Bonnet while we were both at the University of Otago. I am very grateful for her assistance and insights. All errors remain my own.

**Andrew Coleman is a visiting professor at the Asia School of Business. This article is his personal view of retirement policy in New Zealand, based on academic study.

Coleman is on extended leave from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, while working overseas. The views expressed in this article do not represent the RBNZ and are unrelated to work conducted at the Bank, which has no responsibility for retirement policy in New Zealand.

130 Comments

Good to see this discussion being opened up here thanks Andrew. I look forward to the articles.

Yes it is - but Coleman is just another energy-blind, Limits-to-Growth ignoring, economics type.

Money is merely a proxy; a betting slip. Ask what for? And the answer is; processed parts of the planet (there being no other source of anything). They, without exception, are procured using energy.

We are at the peak of that process, heading down the other side. Less and less parts left, year on year.

Yet we are still talking about amassing proxy, rather than questioning the underwrite?

It's fundamentally flawed, is the economics approach.

While I appreciate your continuously reiterated views, everyone gets old and frail eventually, and needs to plan long term for this eventuality. We can speculate that the systems will implode, the sky will fall and many will die with the current level of ignorance of the facts, however despite this everyone must still plan. This discussion is useful and needed, as much as your points 🙂

But only if it is reality-based.

Piling up proxy is foolish - if the supply of what you want, in the future, ain't there.

From a physics POV, pension expectations have required heroic assumptions about future resource/energy supplies.

That does not change. How we divvy up the future, is a discussion worth having; but not in fiat-money terms.

Edit - see what I mean from Jack Lumber lower in the thread. An entirely intelligent persona, addressing only the betting-slips.

Great article Andrew. As a relatively young person in New Zealand, seeing the amount of tax revenue that is dedicated to superannuation payments is something that pains me, especially since there was an alternative that was taken away for it.

It is also something that is clearly not sustainable as the population stops growing. Problem is a lot of people see it as an entitlement and don't think they should be the ones that should have to give it up. This is true with those in or close to retirement, but also flows to a younger crowd where I have heard and seen a mentality of "if they got it I should get it". Especially if as you suggested the working age groups voted to go away from the current model, then they are just supporting the current retirees until they get to retirement when the tap is turned off and they have to spend their earnings on their own retirement and other peoples retirement.

Personally I think we're going to have to get a little bit tough, as convincing people to change the status quo is going to be hard. It's a tough spot to be in and it's hard to not feel some resentment to the people who voted to get us in this (and many other) unfavourable situations through myopic thinking.

Be aware myopic thinking has not just recently been solved. The current young are just as good at it as previous generations were.

You just dont know it yet.

Don't worry, I'm very aware it hasn't been solved in all of human history and isn't likely to be solved going forward. I'm just hoping we have learnt from the economic thinking and policies of the mid-late 20th century that cause more inequality. I'm not sure NZ has it figured out, however.

Good answer. My point is that inequality is still being caused by supposed modern thinking. Todays people will make mistakes as people did in the past. The availability of knowledge today is much improved but I think that is undermined by other factors and we end up in about the same place.

Back to the subject. No mention of Kiwisaver and no mention of the very generous super schemes in the 80s and 90s which slowly died with NZ manufacturing.

Compulsory Kiwisaver would be a simple, obvious first step and phased in. And for the equality buffs, that includes beneficiaries. You heard it here first.

Except far too much of the population has no income or is below that of most beneficiaries (where even beneficiaries under 65 cannot even afford food, adequate housing and medical GP costs let alone to contribute 3% of income more while they still have to apply for extra top up grants for essential living needs). You can certainly contribute 8% of 0 income but it is going to be costing far more each year just to operate a managed fund that gives people less returns, less information and less support when they need to survive to retirement then most other managed funds. So kiwisaver is a ignorant and discriminatory scheme that will still see significant numbers of poor destitute people in retirement needing significant benefits based on need.

I would expect anyone to know 8% of nothing is still nothing but I guess new people are coming through education systems without this knowledge everyday.

And there it is - in my opinion the death and deliberate destruction of our manufacturing capability is one of the root causes of many of our aliments today. Some how we need to rebuild / re industrialize our capability.

We never really had that much manufacturing capacity. Much of it was just screwing together imported components.

His comment is correct. We did both.

There were at least 6 foundries in Dunedin, in my youth. Maybe more.

As a young Manufacturer in 1974 we received our first Import License. To gain the right to import critical components we first had to prove with letters from 3 other manufactures engaged in the industry of the goods we were importing that they lacked the components necessary to produce the goods we needed. Only then would the Commerce Commission gives us an Annual License (needed to be renewed each year) which dollar capped the amount we could import. The basic law of the land back then-- which led to a very tranquil and egalitarian society--was that "if it could be manufactured in New Zealand-it must be manufactured in New Zealand". For everything else being imported there was an annual limit. And houses were purchased at 3 x's annual Average Incomes--even in Auckland!

.

Definitely seen as an entitlement. A mindset of the current crop of retirees, who want to have their cake and eat it too.

Over in Australia:

Can't we have both? Couple win lottery but lose age pension

https://www.9news.com.au/national/age-pension-australia-couple-win-lott…

Is this correct???

"as a direct consequence of this choice, New Zealand has very high taxes on capital incomes and very low taxes on labour incomes relative to the rest of the OECD."

I tried several different ways to look at that sentence, and they all said the same thing, like you - it's the wrong way around. Maybe it's the 'relative to the OECD' bit that gives it a way out. I couldn't be bothered checking.

I also found this statement odd and against reality.

"as a direct consequence of this choice, New Zealand has very high taxes on capital incomes and very low taxes on labour incomes relative to the rest of the OECD."

This seems back to front. NZ has very limited capital gains taxes, no gift taxes, no inheritance taxes and no wealth taxes. Because of this we over tax labour.

The reason we don't have those kinds of envy taxes is because everyone knows that rich people will leave the country.

It's all been done before.

In a fair society all forms of income should be taxed.

Has envy got anything to do with higher taxes on higher salaries? Or is that PAYE not envy based?

I am just trying to understand your feelings.

If rich people just use their money to exploit less well off by over buying land and housing, then change it quick and bid them fairwell. The remainder will enjoy spending half the about they do for shelter.

Hello

Actually, it is correct. New Zealanders have LOW rates of tax on labour incomes and HIGH rates of tax on capital incomes such as interest, dividends, and profits. This surprises most people, but cross-country data from the OECD has shown this for a couple of decades now. It is also supported by other sources, such as the cross-country surveys conducted by the World Bank in conjunction with PWC.

Income taxes are paid when incomes are first earned, in contrast to expenditure taxes (like GST) that are paid when income is spent. Income taxes can be split into two types: general income taxes, applied to all types of income (capital and labour); and social security taxes, just applied to labour incomes. New Zealand has relatively high "general" income taxes applied to both types of income. However, it has very low social security taxes. The combination of a high general income tax and a low social security tax means total taxes on labour incomes are low by OECD standards. The high "general" tax means taxes on capital income are high by OECD standards, even though New Zealand does not have a capital gains tax. The way we tax investments made in special retirement savings accounts such as KiwiSaver is also different from the way they are taxed in most OECD countries, which also contributes.

I shall be examining New Zealand's unusual tax system in the middle of the series. You can't squeeze everything in one article! For those who can't wait, this issue is discussed at length in a paper written five years ago that can be sourced from the University of Otago. The OECD data sources are presented and referenced there as well.

Coleman, A. (2019). Taxing capital income in New Zealand: an international perspective. University of Otago Discussion Paper 1902.

Andrew Coleman

+1, thanks for the clarification.

and HIGH rates of tax on capital incomes such as interest, dividends...

Agreed, as pointed out by the Tax Working Group (but mainly in the context of under-taxation of capital gains on property).

Is there a better break down of income taxes vs capital taxes across the OECD???

https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-sub-issues/globa…

This reference only shows a small difference across taxes

NZ 41+16+0 = 57% income, profits, gains + corporate income & gains + social security (this is mixed income and capital)

OECD 24+10+26= 60%

NZ 29+7 = 36% GST + other taxes on goods and services

OECD 21+11 = 32%

I see what you mean now.

And dont forget the wealth tax on assets in the form of FIF taxes on international assets.

capital incomes

Does your definition of 'capital income' exclude 'capital gains'?

Andrew it’s quite misleading to argue NZ has ‘LOW rates of tax on labour incomes and HIGH rates of tax on capital incomes such as interest, dividends, and profits.” If anything, tax rates on income from capital can be lower than on a similar level of income derived from labour. Eg, the 28% company tax rate, PIE investments.

What you are actually saying is NZ does not use dedicated taxes for social security payments (such as pensions) that are imposed only on labour incomes as much as other OECD countries. That is a different thing altogether. And moving towards more use of this would only exacerbate the inequities of our tax system and its bias towards capital.

Yes, obviously a mistake and was intended to read the opposite. Agree that we grossly overtax our working people who provide the comfortable standard of living to the privileged bearers of non-earned wealth - gained via asset-growth, gifts and inherited wealth acquired tax-free and with little or no effort. This growing wealth disparity simply cannot continue to go unaddressed. We need brave, enduring politicians to change the tax system - and a independent media to help brave politicians to endure and lock-in the new system.

Hello

I think it is useful to distinguish between the what the numbers say, and what your preferences are. It is true that New Zealand is currently one of the few countries not to use either social security taxes to fund government pensions, or have a compulsory saving scheme. It is also true that countries that have social security taxes that only apply to labour incomes have a tax system that means someone earning $50,000 from labour income will pay more tax than someone earning $50000 from capital income. Whether or not you think this is a good idea or not is a different matter. Most countries think it is a good idea and have adopted a system where labour incomes are taxed at higher rates than capital incomes. Since New Zealand does not do this very much, although there are clear exceptions for some classes of income derived from residential housing, we tend to have low taxes on labour incomes relative to other countries, and high taxes on capital incomes relative to other countries. OECD data indicates this is been the case for some time, even though we don't have a capital gains tax. While people might think it is a bad idea to tax labour incomes at higher rates than capital incomes, but this shouldn't distract us from whether or not it happens. It turns out that most tax theorists and most countries think it is a good idea to tax capital incomes less than labour incomes. This in fact is a major principle of the tax systems adopted in most Scandinavian countries for reasons that will be looked at in the course of the series - and these countries are widely considered to be amongst the most equal on earth.

The question that I think is of interest concerns the economic implication of having relatively low taxes on labour incomes and relatively high taxes on capital incomes. There is often a tradeoff between fairness and effectiveness when it comes to designing taxes and most countries have decided it is better to use social security taxes to fund pensions than to equalise taxes on capital and labour incomes. As we shall see, it could well be the case that raising taxes on capital incomes but not owner-occupied housing artificially raises house prices. If this is the case, people could be better off having higher taxes on labour incomes and lower taxes on capital incomes, even if this does not seem fair, because it reduces the extent that house prices are artificially increased. I don't claim to have any expertise on deciding what is fair or not. But it is useful to look at the consequences of different systems before deciding one system is better than other. That is simply my aim in this series - to try and examine the consequences of different tax and retirement systems, without making judgements about which is better or not. You can come to your own judgements. Later, however, I will report survey evidence that shows to some extent what people want out of a retirement and tax system.

AC

Many (most?) countries that tax capital gains explicitly, do so at a lower rate than income tax to account for the 'inflation' component of that income i.e. the real gain is generally not as big as it appears. Here we tax it at the same rate as normal income.

Yes it's often avoided, particularly by the 'accidental capital gain' property brigade, but when it is taxed the rate is high.

Going to be a hard conversation to have unless NZ First climbs onboard, ACT is happy to have it.

I think we need to move to compulsory at 18, no more of this TEC salaries rort, and 10%.

In Aussie super if you have no private is means tested.

This week in Australia. If they were Kiwis they'd get the lottery win and keep the super.

Can't we have both? Couple win lottery but lose age pension

https://www.9news.com.au/national/age-pension-australia-couple-win-lott…

Means testing is needed. By doing so we will actually have enough to support those who cannot get an income now and increase benefits for many who cannot even afford to see a GP. In real terms we have been paying millionaires benefits while denying many of the poor and destitute medical access & essential needs. Hence kiwisaver is more beneficial for the wealthy, with significant property investments &incomes yet meaningless and exclusionary to those who are poor & destitute. Yet we fund more money towards the former in more benefits, grants and sweeteners targeting them then we do for the later. Hence the huge difference in benefits for those over 65 and those under 65 (with significant exemptions denying many kiwis any income at all). It may be unfavourable but those with significant income never needed the pension benefit in the first place and can easily live without it. Even if they were without the main income in 1 day due to substantial injury the most drastic solution is they would sell an investment property or make a claim to existing investment accounts while collecting significant ACC support (if it was illness/disease based e.g. ALS that would make them bedridden in a day, even those the most rapidly disabling conditions still have long lead times, then they could easily still retain a higher standard of living then most people and the existing benefit system for those under 65 is supposedly "enough" for anyone to live on even though many are still excluded from it). In the later case by sheltering those most able to politically make changes we have accepted a significantly inadequate and harmful support system for those who actually need benefit support due to significant life events they had no control over.

Pacifica - in my view we would be much better to keep and extend universal benefits ( bring back the universal family benefit) and to pay for that we simply adopt more progressive income taxes to fund. Means tested benefits are very expensive to administer, can often be circumvented by the well off and result in very high marginal tax rates as benefits are abated. We should start by reintroducing universal family benefit in place of the family tax credit.

Sounds good, let's vote on it.

You could always start it now and a) have extra payments for those who make contributions and b) keep those older folks as they were. Then wean it the other way.

So you have to pay, you get more for it, and if you're too old you're still OK.

A lot of the boomers are retired by now. 1949 = 75 years old.

Means testing will require a serious look at trust law. Adjusting (a bit) for people working past 65 should be easier.

Just call it what it is, a welfare benefit.

You be surprised how many won’t want to be seen on the benefit.

That's why the 90 year old American system is so popular--its anything but welfare since for the past 40 years for every $1 earned over 15 cents is taxed as Payroll Tax--separate from Income Tax. Thus while those earning under $50,000 per year if a family pay little Income Tax at least $7,600 of $50,000 is paid into the Social Security Trust Fund so that when you reach 62 you can begin withdrawing (though you will then only collect 75% of full amount, which triggers now at age 67, but if you wait to collect till 70 then you increase your monthly retirement check by 8% per year which means you can collect about 125% of full retirement benefit by waiting. The more you pay in the bigger your benefit. Your contributions are capped once your payroll reaches about $170,000 after that little is paid in Payroll taxes. And importantly the wage earner contributes only half the 15.2%--the other half if matched by the employer--or you if you are self employed.

Bottom Line-- a top earner husband and wife combined are paid over $90,000 per year in New Zealand dollars. On the other hand if you were a low wage earner and your contributions were much lower than so to is your retirement Social Security payment. And that tax also pays for Socialized Medicine for the over 65 year olds.

Thanks Andrew. I was a student of yours at the University of Otago, it's great to see you still talking about this issue.

Before implementing major reform, I would expect that we first implement the least-effort, least controversial measure of reducing super payments for over-65s who continue to work. The payment could easily be abated at a rate of, say, 10c on every dollar earned over $80,000. As a working age person who doesn't expect to receive much, if anything, in the way of a pension, I think it's pretty crook that 65-70 year old lawyers, doctors, and businesspeople draw a pension while earning a healthy income.

Most New Zealanders probably agree with me. Those who don't agree probably vote for NZ First. The sooner Winston Peters leaves politics, the better.

I totally agree, maybe even more so. Does someone earning $80,000 need the super on top of their income. Let's call it what it is, High Class Welfare.

Of course we hear from some" I had to pay 66% tax back in Muldoons day", like there is no limit to what the world owes me, even after 40 years. When do we break the cycle?

LVT 0.33% on ALL residential and commercial land, sufficient to cover all social housing costs in each region. Shifting more tax burden on to land bankers and speculaters, and encourage development. Difficult to avoid.

GST to 17.5 %

Tax free threshold to $25,000, would benefit the less fortunate superannuants, with plenty of scope to reduce all other income tax brackets,increasing debt repayment and scope for retirement savings. Increase the superannuation age up to 67 in line with other OECD countries

What isn't CENTRE Right about that?

Even if student fees were increased, and more people were required to use private healthcare/elective surgery, the biggest handicap to the younger generation is a disproportionate tax system which favour's land holders, adding undue pressure to business.

Now is the time for the government to take, relieve, and put the money where the mouth is

Is this statement the wrong way around?

New Zealand has very high taxes on capital incomes and very low taxes on labour incomes relative to the rest of the OECD.

absolutely.

Is he specifically talking about tax on retirement savings?

NZ National Super will break. Must break.

Let's get ahead of that disaster and replace it with universal, large contribution, Kiwisaver.

Phased change over would take say 30 years.

No No No No

That solves NOTHING.

You're still playing with future-betting-slips. Kiwisaver is part of the ponzi too.

Why is it so hard? https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/ Read the first 2 posts. Why is it that people go into this default 'money is always a store of wealth' thing? It bl--dy well isn't. In any proxy form. If the planetary underwrite ain't there, its worth jack.

It wont be widely understood until it manifests....and those that understand are crossing their fingers and hoping its later rather than sooner.

I agree with you on some level pdk, but you're asking people to stop saving for their future because some day money will not be worth anything. People have had their whole lives pass by waiting for the same thing, meanwhile missing out because of it.

People hear you but there's a reason they're not rushing to change. It's a bet almost everyone is willing to take.

At least a partial antidote - buy what you know you will need, ahead of time.

Doesn't work for perishables, sure, but for non?

I've been doing that for 20 years...

Buy land.

if you really believe pdk breed working horses.

if you really believe PDK build a fallout shelter, complete with a community undergoing social experiments for amusement and to see the world burn.

"I don't want to set the world on fire. I just want to start a flame in your heart"

Protip in any scenario, most animals are more costly to keep & breed then are actually needed for tasks and with sufficient human capital at NZs current level of low productivity you don't need the animals. If you use any form of productivity improvements then really the animals are exceptionally wasteful in resource costs.

The only animals truly needed and used are those providing significant sensory support which humans cannot provide themselves and tech has not been able to support or replace either (even high cost tech models).

Well those and the pollinators using senses to identify potential and then as a side effect further food generation. However humans have already worked out replacements for needing those.

I think the proposal in part is to tax the ownership of land and force the serfs into funding and being reliant on. the growth of the planet eating economic super organism, even more so than they are now. At least capital gains on property can be looked at as a retirement nest egg, in an otherwise low wage economy. If anyone was serious about the deliberately created property bubble( the financial sector would like that cash funneled their way), they would look at mass immigration no one asked for, excepting property developers, bankers, immigration consultants, yeast like politicians and low quality educational businesses, of course.

There are many many people that do exactly what you do and more, but they also put money aside for their future retirement needs or whatever. Currency/legal tender is the mainstream way of existing in society, and that is not changing.

It will inevitably change - not to be confused with loose change....

That is my whole point - debt-betting on the future is ALREADY in overshoot itself.

Well there is always the zombie apocalypse scenario using the same equally valid methods as PDKs predictive models.

That aside moving from cash we have always switched to other forms of tradable goods and items, e.g. drugs, food, materials, tokens etc. However often once a fixed tradable item that is easily available is identified people do work out measures for using that in place of the old traditional money. Right back to the formation of the oldest counting systems & all systems of trade without money in history. But I doubt some people realize just how prevalent the availability & alternative forms of trading with non fiat monetary items is from the outset because of fixed siloed thinking that completely ignores all of human history and behavior.

Unless the downfall of humanity is extremely sudden, that wipes out nearly all human life as we know it, none of the effects PDK opines will come to pass. Even the black death was not significant enough. All scenarios point to slow descents with punctuated equilibrium. This is also the key to movements & drivers in species development as well. Black swans like PDKs scenario, the alien invasion predictions, zombies, complete outright nuclear annihilation etc are often not even worth considering because should they come to pass there is nothing more then survival, (what is retirement in an all out nuclear war, the concept becomes meaningless and so is any policy in place currently or indeed any form of government).

There is no point to applying the survival methods of some extreme future unknown when it would not affect any outcome of the events itself or whether you will be in that future at all. E.g. no point building a shelter if you don't plan to build it for every eventuality and are not in it 24/7 to start with. Unless you intend to live like there are no other humans or laws on the planet you will never be truly prepared and our current society has humans and laws that have to be considered. I don't see many people training to do their own home surgery without anesthetic, (trust me it helps to have nerve failure there). How many have also radioactive machine experience and have expensive medical scan machines close to hand and optional individual generators? So it is unlikely anyone will be prepared truly for retirement post current society collapse.

I guess PDK could always try homeopathy in their scenario when they are older. I am sure that will be swell for them.

There are no non perishables, even sauerkraut goes bad (points for anyone who knows that reference).

Ironically you miss key items and skills needed and if all you have is some non perishables & a little off the grid home you are extremely unprepared for even most natural events that happen on an annual basis. I get it you think you can live a 'plan ahead, out for your own' lifestyle but you never started life free of people and you are even more dependent on others as you get older. Its great though you brought into the marketing ploys with overconfidence without skilled research. There is such high hopes for you yet by many in the retail sector. At best buying what you think you might need ahead of time only works in optimal predictive conditions, lots of stability with closed systems and massive assumptions that exclude most aspects of human life. It does really poorly even when adding in even just the effects of natural events (both external and internal to the human body).

The pain of losing Super cannot be pushed entirely to younger generations. Spread the load by income and asset testing superannuants now, and increasing the age of entitlement over the next decade.

This reduces the money bleeding from the young to pensioners and gives them a better chance of providing for their own, as well as their parents and grandparents, retirements.

My biggest concern is the lack of balance. Andrew is talking about taxes but doesn't mention GST at all. No one can discuss in anyway the tax burden on people without including the impact of GST which as I understand it, dramatically shifts the way we compare to other nations.

Other omissions that are concerning are the causal factors which are significant. But it is important to note that at the time Piggy Muldoon in his hubris was essentially out of control in his spending, and the pension fund, which he couldn't touch was becoming an embarrassment while he wasted other tax payer funds. So he changed the law and in doing so betrayed every tax payer in the country, while he assuaged his ego. Technology of the time did not give the public the access to information that it does today, so there was no way people could fully understand the implications of what he and his Government were doing at the time.

A bigger concern here is that the current crop of politicians are routinely demonstrating that they lack the knowledge and understanding of the economy, and economics in general to make good quality decisions. Is change required? Probably. Am I confident that good quality change without being harmful to some sectors of society can be implemented? Hell no!

Pollies have to peddle to the here and now, to a reasonably ill-informed voter base. Even if they knew themselves. But the discipline Coleman represents, is responsible for much if the ill-information; I expect no useful contribution from that quarter.

Hello Murray

Don't worry, GST will be be covered later in the series. Most economists (including me) think expenditure taxes (which tax income when it is spent) such as GST have fewer disadvantages than income taxes which tax income when it is first earned. New Zealand has an orthodox approach to GST, and raises a fairly typical amount of tax from GST. One of the downsides of GST is that it tends to be regressive, but this could be fixed if a government wanted to consider ways of modifying GST collection.

AC

Very much appreciate the response Andrew. Do you consider alternate tax methods as part of your analysis such as a "Tobin Tax" (financial transaction tax)? I've heard many views but not much that is definitive.

While I agree with the point about relative taxes on capital vs labour income

Its effects are not trivial: as a direct consequence of this choice, New Zealand has very high taxes on labour incomes and very low taxes on capital incomes relative to the rest of the OECD.

The choice to fund NZ super out of general taxation and not a social security style tax actually pushes NZ in the other direction relative to countries with social security taxes that are only applied to labour income.

NZ has low taxes on capital incomes due to the choice to have neither capital gains taxes nor wealth taxes, not the decision to fund super from general taxation vs a social security tax. Note that the FIF tax regime does mean we have taxes on capital for foreign assets.

My apologies, somewhere in the writing and editing process there was a mix up. This is now fixed. As I have explained in a post above, New Zealand has LOW taxes applied to labour incomes and HIGH taxes applied to capital incomes, even though New Zealand lacks a capital gains tax. There will be a series of posts about New Zealand's very unusual tax system in the middle of the series.

Income taxes are paid when incomes are first earned, in contrast to expenditure taxes (like GST) that are paid when income is spent. Income taxes can be split into two types: general income taxes, applied to all types of income (capital and labour); and social security taxes, just applied to labour incomes. New Zealand has relatively high "general" income taxes applied to both types of income. However, it has very low social security taxes. The combination of a high general income tax and a low social security tax means total taxes on labour incomes are low by OECD standards. The high "general" tax means taxes on capital income are high by OECD standards, even though New Zealand does not have a capital gains tax. The way we tax investments made in special retirement savings accounts such as KiwiSaver is also different from the way they are taxed in most OECD countries, which also contributes.

I shall be examining New Zealand's unusual tax system in the middle of the series. You can't squeeze everything in one article! For those who can't wait, this issue is discussed at length in a paper written five years ago that can be sourced from the University of Otago. The OECD data sources are presented and referenced there as well.

Coleman, A. (2019). Taxing capital income in New Zealand: an international perspective. University of Otago Discussion Paper 1902.

AC

"HIGH taxes applied to capital incomes, even though New Zealand lacks a capital gains tax." But that's the point, isn't it? You shouldn't divorce the highest income earner across the economy; the profit for many decades of property speculation (and, yes Capital Gains are INCOME, and MUST be taxed in the future!), from capital income - and as you note (no Capital Gains Tax), we still do.

Fix that, and any recalibration of the rest of the tax system is easier.

So basically we have high taxes on SOME forms of capital incomes whilst other forms of capital incomes are basically tax free.

Yes, that's what I'd like clarified. Are capital gains on assets (be they property/businesses/shares) excluded, or included, in the definition of 'capital incomes' here. I suspect they are not included as part of the 'capital income'.

A fundamental issue with Capital taxes on property is firstly tax receipts are intermittent, next the inflationery aspect must be fully discounted, the so called income must be attributed to each year of ownership - this is difficult so may be addressed by a discount rate or on total tax. As much residential property is used as security for Bank loans the effect of selling a property means the tax effectively reduces the security amount if the net proceeds are invested in a replacement and for employees moving a disincentive unless the employer tops up or the move is to a cheaper housing area - such impediments will hinder movement of employees and detrimental to business. It is also unacceptable to taxpayers and posion to any Govt that legislates realising the electorate will take their revenge next election and consign that party to the opposition benches and if the opposition party promises repeal transport back to the Beehive will be in a 12 seater minibus.

I disagree that Capital Gains are income but if you insist then taxes should be attributed to the years over wwhihc the gains arose, to avoid the difficulty of attribution over say a 20 year gain you need to adjust for inflation and reflect the attribution in a lower level of tax. Taxing land will be viewed by many as a land grab where the land returns no income from which a tax can be paid.

One of the most important issues:

The majority of kiwis have the foresight to see and have seen that the only way to retire comfortably in New Zealand was to own property.

Unfortunately this does nothing for the overall economic health of the country.

Past and present governments have continued to give this area tax breaks only because it was deemed to be a convenient way to ring fence the population and enable the government's to keep the superannuation bill for past generations lower.

We are at now at a cusp of a potential problem of population decrease and higher rates of an aged population entering retirement.

We must,for the sake of our children and children's children,radically shake up the whole tax system to reflect the contemporary workforce and society as it is now and into the future.

To not address it,would be tantamount to enabling the system to throw the future population of presently young people to the lions of abject retirement poverty.

Brilliantly put. One generation timed it lucky, and rode the WW2-until-now sled.

But it is at the bottom of the run, and they didn't put in a chairlift.

Put another way: Entropy is irreversible.

It goes deeper than the tax system though - it's entire belief systems, indoctrinated economic and financial thinking - a fear and scarcity based "civilisation".

Retirement is a relatively new construct and owning property to achieve it an even newer construct.

Absolutly correct and amazing how few see this even less understand the implications and that includes Govt central and local.

Corporal Muldoon...don't remind me...his 66% "temporary tax surcharge".

Theft on a giant scale that precipitated dozens of tax avoidance schemes and emigration by thousands of kiwis to Queensland.

"Many rich countries such as Norway, Sweden or Germany already collect more taxes than New Zealand"

I'm almost 100% sure that NZ has higher taxes than Germany. They have compulsory health insurance, which we don't have. Also they, like most countries, do not tax contributions to superannuation. I believe that's a peculiarity to NZ, and it's a little bit like economic vandalism of our superannuation funds.

45% top tax rate. When I worked there they separated tax health and pension. Also if you declared yourself religious 5% for the church was deducted.

I opted out of paying church tax, which was satisfying. The rich tax only kicks in at 277k euros ($491k NZD)

Compulsory Kiwisaver - the state does a min contribution for those who cant work, can debate about contribution %s, taxing contributions etc.

At 65 (or make between 60 and 70) - 50% as a lump payment, 50% as an annuity per fortnight.

A minimum living amount is set, by someone independent - different amounts between 60 and 70.

This amount less your annuity payment is then topped up by the state - if you have more than the set amount get zero.

The state payment tops up - not the base load.

Keep NZ super fund going to build up even more to fund some of this so less/not reliant on tax revenues.

In effect take pension right outside the standard tax revenues/Government expenditure on health, education etc.

Will take 20 to 30 years to fully transplant but have to start somewhere and use compounding. Imagine if Muldoon had not changed the scheme - we would be a very wealthy country and not short on capital. It means thinking longer than the weekend which is not a strength in NZ..

I would expect anyone to know 8% of nothing is still nothing but I guess new people are coming through education systems without this knowledge everyday. Protip significant amounts of our poor have below the income of most beneficiaries or no income at all. Try investing in kiwisaver with no income. I am sure using your logic you will get great returns with 8% of nothing invested. sigh a new person without maths skills everyday.

I agree - that’s why the poor would have a contribution made by the state to their account so that when they get to an age they have something. They get a lump of cash plus a payment topped up by the state. It will be a lot less than others who earned more but it’s more than the zero they would get otherwise. As a person who pays a lot of tax I’m more than happy to fund this so everyone has something to look forward to and a chance to have a dignified older age. It won’t be luxury by any means but probably more than they have ever had before.

Is there modelling to show what the effect of means testing the pension would achieve in terms of savings? I've seen estimates of 20% would lose access to the pension, but that is based on Australian outcomes. I posit that the NZ reduction in pensioners would be a lot lower than that, simply because we do not have as many wealthy New Zealanders with big retirement savings, because we dont have a compulsory retirement savings scheme thats been in operation for decades and we discourage share market investments. Aside from the few who own a rental property, the majority of retirees have nothing. So maybe means testing might kick 5% off the pension max?

And that's before everyone starts gifting assets and setting up trusts to alienate their assets, in order to qualify for what they believe they are "entitled" to.

NZ is also allowing young people to withdraw all their KiwiSaver to buy a house, which sets back their retirement savings by decades. (a 20 year old who contributes to super for 10 years and then stops completely, will still have more in retirement savings than the 30 year old who pulls all their super money after 10 years of contributions to buy a house and then starts over with contributions for the next 40 years. Thats the maths of compounding interest). If NZ is serious about retirement savings it must stop people from raiding their super to buy houses.

Can we put that another way?

It must stop people raiding the future, to pay for the present.

Hello K.W.

I believe the Treasury has estimated the effect of imposing a means test on NZ Superannuation, as part of their regular reporting on the long term fiscal consequences of New Zealand's tax and expenditure settings. Susan St John from the University of Auckland has written extensively about this as well, as it is a policy she favours. You could look up her website. I have not done a detailed cost analysis of the effect of means testing, in part because of the difficulty of estimating the indirect feedback effects of such a policy. These include the way people over 65 may change their hours of work and the way people may reallocate their investments to sidestep such a policy. Most modelling work suggests these indirect effects are large, and since I do not know how to do them properly I have not attempted them. Most of the quantitative work in NZ has ignored the indirect feedback effects because they are so difficult to do.

Later in the series we shall look at survey evidence that suggests a means-test would be very unpopular - avoiding a means test is the most important facet of retirement income policy for the largest number of people. There are other ways of achieving distributional outcomes without means tests that will be discussed later. These may appeal to a larger group of people. Finding policies that have widespread support is quite important - it is one of the reasons means-tests were abolished in the 1990s.

AC

Susan St John favours universal super coupled with specific progressive income tax thresholds.

In other words it is income means tested after the event, not wealth means tested in advance as to whether super will paid (as it is in Australia). The cost of the in advance means testing, aside from the gross intrusion into peoples' privacy is administratively very likely much greater than a universal payment coupled with specific progressive income tax thresholds.

If you started with just the "retirees" that are actually still working and earning over $100k p.a., there's 50k of them and that's $1b per year of savings.

Lots of calls for a CGT.

If there's such a gaping hole in the tax system why aren't you guys out there taking advantage of it?

That is like arguing someone can't suggest Sanitarium pay company tax on their earnings, while at the same time not running a tax exempt business.

Or, to really stretch the example, if you thing criminals get off so easy, why are you out there being one?

Because there's serious consequences for criminals if they get caught.

There's no consequences for arranging your finances to take advantage of capital gains. If gains are taxable, then losses will be deductible...right?

It's all been done before, like most things. The tax department decided in its wisdom to tax those that were making capital gains on the stock market in 1987.

Then the colossal 1987 crash happened and the IRD had to make losses deductible. It cost the govt. hundreds of millions.

Japan taxes capital gains, but losses from capital transactions are generally not deductible against ordinary income. However, there are provisions for carrying forward losses to offset future gains.

Which is what we should be doing. It's called a capital GAINS tax, not a Capital Tax, and any losses can be carried forwards to offset against future gains (if any) within say 7 years. Then...just like airports, they expire.

How do you know they're not? I occasionally sell some of my shares for various reasons, and don't have to pay tax on the gains - it's great. Doesn't mean I'm against a proper capital gains tax being put in place.

Why would you want to sabotage your own capital gains?

To correct the greatest imbalance in NZ. Taxing Land speculators...like you.

I think it would be more fair. Sometimes I argue for things that would benefit society even if it's not the ideal course for me.

Wingman do you have to hold the title for 2 years to avoid cap gains tax, or are you processing all profits as income.

There's no capital gains on selling your own house. It's hard to believe there's people out there who would just love to pay more tax.

Why don't they just give more to the government every year? If land speculation is such a great risk-free deal....be my guest...have a go.

Or don't you have what it takes?

It doesn't make society any better or fairer if I pay a little more tax out of the goodness of my own heart, but rebalancing the whole structure can. Even if that has the same end result on my wallet.

Socialists seem to forget that capital gains tax also means capital loss refunds. In the event of some catastrophic meltdown, the NZ govt.would have to cough up those losses. Like after the 1987 crash.

Not many politicians seem to be willing to risk it.

When you make tax laws, you are free to design them as you please. There is no universal unbreakable rule of the universe that you have to offset income tax to people who lose money in property.

Regardless, NZ is the only OECD country without a comprehensive capital gains tax. We are the outliers in the world in this respect! To suggest we would be breaking modern norms is very misleading.

You really think the govt. could get away with taxing gains, but not making losses deductible? I wouldn't think so.

There's several reasons no NZ govt. has had the resolve to do it, and one of them is that they would be evicted at the next election.

You haven't answered my question. If buying and selling the occasional property is such a terrific tax-free deal, why aren't you doing it yourself? You'll only need to borrow about a million to get started.

I just don't get that....there's complaints here that there's tax avoidance occurring, but they're not taking advantage of this 'perk' themselves.

You are in a minority on this one, the majority of Kiwis support a capital gains tax so I expect a government will fall in line eventually. Even most National supporters want it, and half of ACT supporters.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/300979367/new-survey-shows-wi…

However, even more people want windfall profit taxes so I'm in a minority there as I don't generally support them.

"Windfall profits tax?" Is there a "catastrophic losses" tax refund? If the market goes the other way, for example?

If a majority of kiwis support a CGT, why isn't there one? Because there'll be serious consequences for those that enact it.

I'm at a complete loss to understand why there's this apparent 'opportunity' to make tax-free capital gains, but no one here is actually doing it?

No, generally the windfall is taxed in the good times and no-one cares about the bad times, which is why I don't support such taxes. You can see plenty of examples around Europe in recent years.

I think that Kiwis supporting cap gains tax is likely quite a new thing brought about by the rise of anti-property investor mentality. If that persists, the tax will follow.

Like I said earlier, I am making capital gains, but that isn't relevant to the argument as far as I'm concerned.

I'd expect capital gains to be ringfenced away from regular income. So yes, big capital losses lead to a reduction in capital gains take, just like business taxes fall in recessions etc.

I'm not sure why you think anyone has forgotten this.

no but builders have to live in their own house not to be captured for bright line for 2 years... suggest you talk to your accountant, you cannot just subdivide and build 6 houses and say no cap gain, the gains are taxable as you are a property developer.

Kiwisaver needs to be tax advantaged. The $10 a week tax credit which hasn't been increased ever isn't tax advantaged that wouldn't even buy you an egg on toast now. Defer tax until withdrawal or cut the tax rate to 15% on Kiwisaver PIEs.

I dont know why we cant just merge Kiwisaver with Australian Super and let the Aussies take over and manage NZ super as well. 15% tax on contributions, 15% income tax while in accumulation phase, and tax free on pension phase.

I'd argue no CGT is probably the biggest issue when it comes to the low productivity of our economy.

Remove housing investment as the best option for investment they it will force more investment into productive parts of the economy.

Like what? The stock market?

The NZ stock market is a basket case. And international shares attact a 5% wealth tax. Its not a choice that Kiwis make to buy investment property, its their only real option.

Tax reform? All good, yes, capital gains, land tax, increased low thresholds etc.

People 'saving up' for retirement? What are they actually saving? Shares in companies?

Now, who benefits from pension funds taking a % of workers' wages from them and using that money to buy shares from shareholders? You basically end up with a bloated financial management system and fund managers, company directors and wealthy equity holders extracting rent from an increasingly gigantic pyramid scheme.

Now, what happens 30 years later when that worker retires? Let's assume (hope) that disasters have not wiped out the value of the pension fund's share portfolio. What then? The fund starts paying out to the newly minted pensioner. Hopefully the income will be enough for them to live on, but many will need additional support - aged care, residential care, nursing even. Where will the additional doctors, nurses, care workers, hospitals, public transport options etc come from?

Those real resources will have to be taken away from other things - less shop workers / more care workers, less management consultants / more medical consultants, less McMansions, more McMedical Centres.

Now, do you see the problem here? Saving up money / shares for the future does not create additional capacity in the future; the country will have to direct more of its limited real resources to the things an older population needs. At the same time we will be doing the same to support climate adaptation projects and dealing with whatever the hell else is going on in 2060.

So, how will we reprioritise those real resources? Will we have a bidding war for staff to work in aged care facilities - prising staff away from working at our one remaining supermarket chain? Is a bidding war for limited resources fueled by liquidated 'savings' the best approach to a necessary prioritisation? No. This is what taxes were designed to do - to reduce demand for things that are less important (or even harmful) to the country and ensure that Govts could provision real resources for the population.

So, long rant, but my point is simple. If you want to create the illusion / incentive of saving - use something like Govt war bonds that create financial instruments that are both Govt debt and private sector assets (saving). Then use higher taxes in the future to create the space in the economy for pensioners to buy what they need in the future (as they are paid back by Govt for their 'saving'). Don't provide yet another opportunity for the financial system to extract rent. It's madness.

*Worth noting that pension funds are well-stocked with Govt bonds (debt) already. Let's cut out the middle man.

And that summarises it rather well.

Yes sadly most retirement staff cannot even afford the living needs access & living standards of retirees. Many are on rock bottom wages and can barely afford food and housing. So many cannot save or plan for a retirement adequately while performing retiree support roles. So expect to see it continue to be an undesirable career well into the future with a cost of living crisis. Abuse is rife so the lifestyles with the current industry is really shocking. If we are to plan for anything it is to expect the actual case now where the health is beyond code black and if you are having a heart attack or respiratory failure they may or may not get to you in the next 2 hours or more. Plan for how you will survive or plan end of life after a severe stroke, or when hit by cancer but have no GP support & no specialist access even in a private medical care system.

This is not a scary future scenario. It is one many kiwis face today and is quite common on certain socioeconomic levels. If anything be glad if you have an early death by an unknown unpredictable accident.

Thanks for the comment. Yes, I know this sector very well indeed and staff work tirelessly for next to nothing, often in very challenging conditions.

The only way that a society gets enough retirement home / care workers under the current low pay, precarious work, unsociable hours model is if people are made truly desperate to work - basically, if other minimum wage jobs are taken, benefits are low, and / or govt effectively subsidise wages (jobseekers for people working part-time).

If aged care had to actually compete for workers, wages would rise to a higher 'real jobs market' level and the cost of care would go up significantly. This would blow govt budgets and household savings. Also worth noting that many aged care companies are only viable because of property interests.

Forcing people to direct a proportion of their savings into pension fund shareholdings to somehow sustain this model in the future is madness.

Probably just worth clearing up one misconception that will be floating around: the British social fund levy is called National Insurance, and it sits at about 2% of income.

It is not ring-fenced for pensions. It just goes in the general fund. It is used to calculate entitlements when you retire (used to be referred to as Stamp.) You can make voluntary Stamp contributions to buy a higher future entitlement. You'd be crazy not to.

Most OECD countries are the same - state pensions are decoupled from the benefit received on draw down. So this article comes across as a bit misleading, because it gives the impression that other countries pre-fund their pensions. They don't. Except for places like Singapore, they pay entitlements out of the general fund, just like we do.

Thanks for this comment. You are right of course: many countries have contributory government pension schemes (a pension scheme where the size of the pension you receive depends to some extent on the amount of taxes you pay) but the social security taxes that people pay are not accumulated in a fund. This is not contradictory. The decision to have a contributary system is separate from the decision to pay pensions immediately from tax receipts (a pay-as-you-go system) or have a system in which tax payments are accumulated and used to pay pension entitlements in the future (a save-as-you go system). You can have a welfare based system like New Zealand's that is operated on pay-as-you-go or save-as-you go principles; and you can have contributory systems operated on pay-as-you-go or save-as-you go principles.

These issues will be discussed in the series or articles. The decision to accumulate tax payments in a sovereign wealth fund (or alternatively have a compulsory saving scheme) has different economic implications from the decision to fund pensions from general taxes or from social security taxes. It is best to consider the issues separately and then choose the combination which is considered most suitable

I notice you studiously avoid my points, Andrew.

Points I learned at, among other venues/sources, Otago University.

Here's some homework from outside your silo, which overrides what your silo knows.

https://nz.search.yahoo.com/search?type=E210US105G0&p=surplus+energy+ec…

https://www.thegreatsimplification.com/ (if you're a complete beginner, try the 'animated series' first.

https://un-denial.com/2024/01/21/by-hideaway-energy-and-electricity/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jiec.13084

https://www.financialsense.com/contributors/chris-martenson/the-trouble…

If you need to understand how to mesh keystroke-issued debt with everything else, this is from the best:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMmChiLZZHg (start @ minute4)

edit - this is the hard-copy https://www.amazon.com.au/Thinking-Systems-Donella-H-Meadows/dp/1603580…

But I'm guessing you will avoid, and avoid the point. Which is that the betting slips you are advocating that folk should pile up, cannot be unlimitedly-underwritten by the physical planet.

It is hard to know where to begin with the large variety of statements that you have made, Mr PDK.

Let us start with energy. There will be an article showing how reform of Retirement income can help solve one of the pressing issues of the 21st century, climate change, by helping with the transformation from black energy to green energy. One of the nice things about this transformation is that it will take advantage of the almost endless supply of energy emanating from the sun. I have written about this before for interest.co.nz if you cannot wait. But, in contrast to your suggestion, it is not true that economists ignore energy or climate change or resource use. Von Neumann was writing about CO2 and climate change in the 1970s. Most modern economic approaches to climate change date back to the 1970s, and for decades have been incorporated into policy. It is true that many politicians have been slow to recognise some of their insights, but even this is changing fast. I suggest you try to read a wider range of orthodox economics before writing it all off

Secondly, it simply is not true that most economists cannot distinguish between money and financial claims , and the underlying real assets in an economy, be they hard capital tools, the routines and intellectual capital that underpin successful firms, government owned roads, or natural resources. Most students learn the difference in their first year courses. Economics can be rather obscure from time to time, but most people realise that changes in real saving and investment behaviour do lead to changes in the quantity and productivity of the assets that are used by firms in an economy. Whether or not some of these investments are worthwhile is a question central to the relative merits of different retirement schemes, as several Nobel prize winning economists demonstrated in the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps you should show these guys some respect and read their work so we can focus on the real choices society should be making, rather than attempting to distract attention by alleging economists can’t tell the difference between a piece of paper or a financial claim on a bank or a firm and the underlying assets of an economy.

The series will take a while; perhaps you should relax, read it as it comes out, and wait a little while before attempting a blanket condemnation. A devastating critique might be a bit more appropriate nearer the end.

I have been in the Limits to Growth space for long enough to recognise 'shooting the messenger to avoid needing to learn' when I see it. Classic is association with superior intellect (Nobel prize-winners - I'm guessing you'll agree there can be Nobel fools too: Scholes and Merton come to mind; Pi extrapolated never gets to 3.2) and curtailing the scope (Climate Change - which I did not mention; not once). They use the put-down to justify - to themselves - avoiding learning that which they need not to know (in this case, my links). It happens all the time, including at senior academic level https://www.interest.co.nz/public-policy/128237/murray-grimwood-says-fu…

Few economists have grasped the Limits to Growth (not Climate Change) and of those who have, even fewer 'get' energy. Your glib solar reference suggests to me you aren't in that number. I rate Malthus, Jevons, Mill, Soddy (his 1926 book I have: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wealth,_Virtual_Wealth_and_Debt ) Boulding and latterly Keen. The rest? Not there.

Please read the links.

edit - I forgot Galbraith

Andrew, all of our economic theory has been written in an environment of growth. All the Sveriges Riksbank Nobel Memorial prizes have been giving out in a time of growth.

That growth is dependent on ever-growing energy usage, 90% of which comes from finite fossil fuels. Once the total amount of energy per capita starts falling, all the economic theories will start to fall apart as their basic assumptions are proved wrong.

Replacing our fossil fuel usage with renewables will not be possible. We are currently not even covering the yearly energy gain with renewables, let alone eating into the other 90%. To go to solar, for example, would require covering an area greater than all the current urbanised area globally but we will run out of resources to make them well before that.

I would recommend the dothemath series and the summarised text book, available for free at Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet (escholarship.org)

Wait you studied at Otago uni... knowing the lecturers that explains a lot of the gaps and the hilarious references (even in those fields Otago has a... reputation for lets say a certain atmosphere). This stuff is not suitable for any debate, even when trolling. Economics sure has no scientific methods and is barely a history course with future predictions based on past events. So using any of it for future estimates/analysis or claim facts is really risible.

You should gone into trades instead of studying anything at Otago... (except perhaps medicine but even then they have courses for people who have not even trained in medical fields to claim they are medical professionals to treat patients now). So yeah, lets keep Otago a plan D to any diploma course you can complete to become accredited to the same degree of professionalism & skills. I have seen many open free courses that will offer the same levels of training as Otago now. Sadly I have had to teach many coming out of Otago courses really simple economic and financial information... it truly saddens me the lack of standards they have & in teaching and the heavy influence towards blog based opinions rather then any scientific or mathematics approach.

Please take this opportunity to retrain even in mathematics analysis fields. Of which most are a cake walk with heavy drinking so just like the experience on offer at Otago.

They teach a very good thing at Otago - critical literacy

You should try it

I was never a student at Otago - or any other - University. I did not claim that - you, as usual, poured out assumption-on-assumption. I said I had learned things there - which is a very different statement.

Further - I began life as an apprentice.

You need to stop and think, before you pour out so much based on so little.

Jonathan Boston's book on the welfare state published by BWB could be worth a read - it discusses the differing political acceptabilities of funding from general taxes v bespoke taxes.

Another example of a bespoke tax that we have is road user charges and petrol tax - both going into the land transport fund.

Great article and like others I am very much looking forward to subsequent ones. As I understand it, another advantage of Australia's compulsory super scheme is that it has built up a very significant source of funds for investing in e.g. Australian equities. If I correctly remember a column from sadly departed Brian Gaynor, Australia has a markedly higher per capita level of investment funds than NZ. I wonder if more successful NZ enterprises would remain NZ owned if we had a similar level of investment funds per capita as Australia's?

Not just listed equities either, most of them are also substantial private equity owners, and have become the biggest form of venture capital funding start ups, along with being big supplyers of private credit.

https://www.afr.com/technology/big-super-is-the-surprise-heavyweight-in…

https://www.afr.com/companies/financial-services/super-funds-step-up-pr…

Funding, eh?

Is that like 'funding into existence'?

This thread is amazing - everyone talking about amassing future betting-slips; nobody asking if there are any races left on the card.

The level of inaccurate and false statements in this article is stunning.

The three major flaws he claims for example.

- very high costs on current and future generations - the level of super is a political priorities decision, as a % of GDP it is not high when compared to many other developed countries, there are extra health and welfare costs from not having a super system such as we have because of the effects of retired living then in poverty

- "means New Zealand eschews some of the most efficient taxes used around the world, but relies on taxes that artificially distort investment decisions and inflate property prices." WTF how does paying universal super preclude capital gains and wealth taxes? (it doesn't)

- "And it exacerbates some dimensions of inequality." Interesting statement given it does the opposite.

Then there is the misrepresentation of the 1997 referendum. It was not a referendum on an in-principle decision to replace super with a compulsory retirement savings scheme (with all the equity issues that inevitably arise with such a scheme). That referendum was on whether NZ should adopt a specific, very detailed retirement savings scheme proposal. There were lots of fish hooks in that proposal.

The lack of recognition of a fundamental difference between most European countries (Euro currency users) and NZ (sovereign currency issuer) is stark.

Robert Muldoon did New Zealand a huge favour by chucking out Roger Douglas's compulsory contributory superannuation and replacing it with a universal pension that survives as NZ Superannuation.

The problem is not NZ Super, but that it is funded out of current taxation. Andrew Coleman supplies the solution himself: 'In one major development, the New Zealand Superannuation Fund was established to change part of the funding of New Zealand superannuation from a pay-as-you-go-basis to a save-as-you-go basis.'

NZ Superannuation can be improved for the present and made fit for the future by doing three things:

1. Increase the after-tax rate of NZ Super for a couple to be no less than the after-tax rate of the minimum wage so that it is enough to live on in dignity for those who really depend on it.

2. Reintroduce a form of the surtax on all other income that was abolished in 1998, so that though NZ Super would remain universally available, those who do not need it would be deterred from applying for it.

3. Abolish state subsidies for private KiwiSaver accounts, and instead greatly increase the funding of the NZ Superannuation Fund as a national savings scheme for disbursement equally to all today's under-45s in 20 years time.

I don't see why hypothecated social security taxes are needed for 1 and 3. What is needed is the introduction of annual land taxes, capital gains taxes, gift taxes and inheritance taxes sufficient to fund a greater NZ Super now, as well as to save for that future payout — and, of course, the commitment of governments to use the revenue for the intended purpose.

Where there's a will, there's a way.

Here are some thoughts from Keith Rankin that apply as much to the debate on NZ Super as they did to unemployment insurance. The issue is one of universality.

https://eveningreport.nz/2022/02/10/keith-rankin-analysis-unemployment-…

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.