By Julia Talbot-Jones & Yigit Saglam*

For more than 25 years, New Zealanders have consistently rated freshwater health as one of their leading environmental concerns. But the issue is strikingly absent from the 2023 election campaign.

Debate of the controversial new water reform law – which places the management of drinking water, wastewater and stormwater with ten publicly owned entities instead of local councils – has been noticeably muted.

Similarly, discussions of the 2020 Essential Freshwater package, which was the government’s response to New Zealanders listing freshwater as the second most important policy issue in 2017, are nowhere to be seen.

Part of the reason could be that the regulatory approach of the Essential Freshwater package has met resistance from farmers and landowners who feel growing pressure from compounding environmental regulations.

Given this, the continued absence of environmental markets for addressing scarcity and improving freshwater quality in New Zealand streams and rivers is a marked policy omission.

Elsewhere in the world, water trading can help improve efficiency and drive water conservation. Trading helps to shift water from low-value to high-value uses or from areas with relative abundance to places of relative scarcity.

Motivated by what we observe in New Zealand and internationally, our new research offers an innovative, alternative approach for managing freshwater in small catchments.

Freshwater and property rights

Freshwater is allocated on a “first come, first served” basis in New Zealand. Since 1991, consents or permits have been granted to water users by local authorities under the Resource Management Act (RMA), usually for periods of up to 30 years.

Although these consents act as de-facto property rights to water, they are not defined as such under the RMA. This makes water “rights” open to interpretation when challenged under law.

Consent holders are also unable to easily trade and exchange their rights. This means water is not necessarily used in the most efficient or effective way. This potentially exacerbates issues of over-allocation and declining water quality.

Part of the ambiguity around water rights is driven by unresolved questions about proprietary rights and Māori interests in water that have arisen because of inconsistent translations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. These complexities make the establishment of property rights to freshwater complicated, with run-on effects for the types of policy tools that can be adopted.

Formal water markets, like those in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin, require property rights to be well defined, defended and divestible. They also have several institutional preconditions, such as low transaction costs and a large number of active traders. These make them appear poorly suited for many small New Zealand catchments.

However, our research suggests that designing water markets as “clubs” could circumvent some of the institutional challenges of implementing formal trading regimes in small New Zealand catchments.

Water clubs: a new model for small catchments

Unlike other countries characterised by large river basins and many active water users, many parts of New Zealand have small catchments with few active users.

Economic theory argues these contexts are unsuitable for formal trading arrangements because the transaction costs associated with establishing an active water market are likely to outweigh any potential efficiency gains from trade.

Designing (or redesigning) water markets as clubs could get around some of the political and economic complexities of New Zealand’s freshwater policy landscape by permitting small groups of users with shared interests to voluntarily trade their water endowment under certain conditions.

In small catchments, the introduction of trading at the group level has the potential to increase the public-good aspects of water such as water quality. It could also improve community wellbeing and encourage people to internalise the costs they may be imposing on other group members.

We also find the club model performs best when the number of active traders is low. This challenges the common assumptions regarding group size and effective market performance.

These results suggest that if water users, such as a group of like-minded farmers involved in a catchment group, were given permission to trade their water consent with other members of their group, they could improve the health of the environment.

They could also enhance the net benefits of their own private agricultural production, compared with the current regulatory status quo.

Although this new “club model” does not comprehensively address the outstanding issues of Māori rights and interests in freshwater, it provides an innovative way to adapt a trading regime to suit New Zealand’s political and geographical context.

Surely innovation is something political leaders would want to discuss on the campaign trail.![]()

*Julia Talbot-Jones, Senior lecturer in Environmental Economy, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and Yigit Saglam, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

7 Comments

"Club" seems an effective way for the 30 houses in our road to organise sharing their solar generation and power use. Thanks for the tip.

Even better might be some modelling whereby a mix of wind and solar could be shared in small groupings. Some houses where wind generation isn't obtrusive can help keep the power going through windy nights. Houses with optimal aspect for solar capture can be the boost during the daytime.

Seems an ok idea but what exactly is meant by a club?

Also

"Surely innovation is something political leaders would want to discuss on the campaign trail"

Have you seen the state of our politics.

Innovation is the last thing they wish to discuss. Status quo from all parties.

Up until perhaps 30 years ago, we had Rural Water Schemes - locally funded, often locally-installed, a local committee fully familiar with what they had and why they had it.

Neoliberal economics - and the last gasp of global growth - removed that local ownership, in the push to privatize everything. That momentum is now on the ebb, and ain't coming back (entropy is becoming too strong a factor). So expect a reversal of the process; eventually we'll be back to a local person going out to fix a local leak.

Not sure what these two academics were trying to achieve - they perhaps need to talk to other disciplines (Dr. Mike Joy would be a good first call).

These 'clubs' already exist in a way. They are called irrigation companies - or Water User Groups. We are part of an irrigation company. We hold shares in the company which allows us to use x litres of water per fortnight. If we don't need to use the water at any time, we allow any other shareholder user who could use the water, to take it - no money changes hands. Likewise if the season is very dry and water take needs to be reduced, the reduction is shared among the users. Otago Regional Council has pretty much a 'use it or lose it' policy now with water consents. Other regional councils have similar policies, so in a NZ context there will be fewwer and fewer consents that have a true 'surplus' of water. As horticulturalists our water consents are only for the months of the year the hort season runs - i.e. not over the winter months. Dairy consents are usually tied to stock numbers plus an allocation for cowsheds. There may have been excessive allocation consents in the past however they are becoming a thing of the past in the progressive regions.

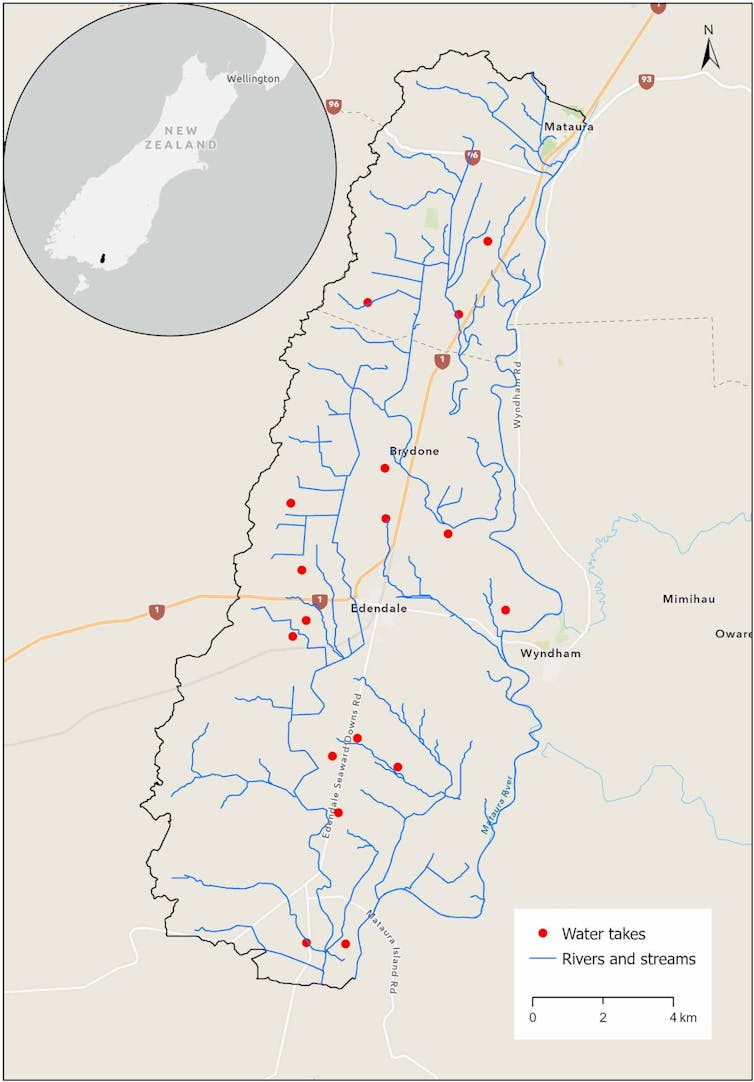

It is interesting that the map is of the Mataura catchment. Approx 18-24mths ago ES deemed an over allocation in parts of the Mataura FMU and called in consents for irrigation, ie contacted farmers and told them they were withdrawing their right to take water for irrigation. Just because you have a long term consent doesn't mean you have long term certainty of use.

As to why isn't it on the campaign trail - a lots has changed in legislation regarding water since current government came to power, and today there are other issues that are concerning more kiwis than water - the current exception perhaps may be Queenstown.

Edit mths ES contactacted farmers

25 million litres unlawfully used for frost protection and irrigation... In another circumstance Ive seen water running across the road like a stream because someone didnt shut their bore pump off (orchard) . I think its time folk thought really seriously about water. I also think Maori inclusion is something folk dread but reality is needs to happen to raise water quality. Nice to spend time trying to circumvent possibles but Queenstown wont be the last town to experience problems if we keep kicking the can down the road.... Lets face it some councils cannot even treat their sewerage correctly.... Dont ask me to dig up more because im sure theres plenty to choose from and theyre only the minority that get caught.

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/bay-of-plenty-times/news/bay-of-plenty-kiwif….

https://sunlive.co.nz/news/162801-second-sewerage-consent-breached.html…

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/piggery-fined-for-discharge-of-effluent/S…

https://www.farmersweekly.co.nz/news/piggery-ordered-to-stop-polluting-…

Therein lies the difference between the Labour/Green approach, and reality.

Economic growth is exponential; to keep it going you need to keep doubling, and some time-interval (3% = 24 years). The result - irrespective of who is doing it - is that you run up against hard resource limits - and it comes on you faster than your are expecting/can react. Queenstown is just an early example of entropy - of which we see more; both more frequently and more 'more'.

Maori merely looked less impactive that Europeans, because they hadn't tapped into such a source of energy. That doesn't mean they are any different - indeed humanity is probably wired to be flawed; the instinct to procreate is required early in a species' trajectory, but is fatal post-overshoot.

Equally reactions to overshoot can be misunderstood; the lgb-whatever brigade have ONE thing in common; a lesser emphasis on species reproduction. Not addressed by media, by anyone.

The problem in a powering-down world, is that 'improvements' will join the list of triaged activities, and all will be hamstrung by increased maintenance demand. Centralisation was the wrong answer to the Limits to Growth question; yet another move 'up', when we need to accept Limits and plan for an orders-of-magnitude downshift.

Which renders ALL political hues incorrect/obsolete, currently.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.