By Chris Trotter*

Which did more for Dunedin – the City Council’s public relations department, or the creators of the “Dunedin Sound”? In any battle for excitement and attraction it would be most unwise to put your money on bureaucracy. Something all governments, and all Ministers for the Arts, would be wise to remember.

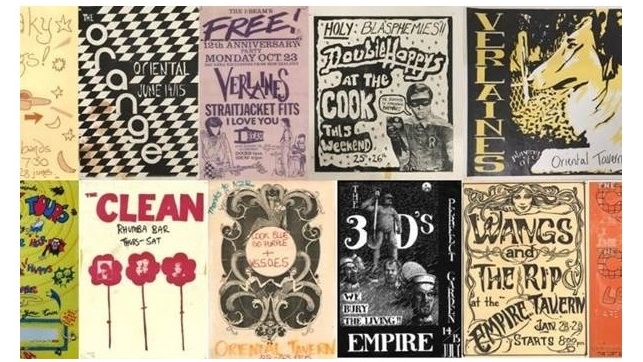

The power of creative communities is little short of miraculous. A handful of self-conscious avant-guardists, playing to each other in the draughty church halls and commercially fragile pubs of the world’s southernmost university city may not have seemed powerful at the time (the early 1980s) but, in remarkably short-order student radio stations from Oregon state to the River Clyde were playing the music of The Clean, The Chills and The Verlaines.

At a time when most Dunedin politicians would’ve characterised the Dunedin Sound as bagpipes and the bells in the varsity clock-tower, indie-music-loving young Americans were thinking “cutting-edge”.

The same thing happened (albeit multiplied by 10) in Wellington. The artistry, this time, was located in Peter Jackson’s Weta Workshop and the ever-expanding army of creatives that marched in lock-step with his success. Could the inspired slogan “Absolutely, Positively, Wellington” have worked half as well had the creative community not made all those cafes, clubs, restaurants and bars the places to be seen, and then supplied them with the people to be seen with?

It works everywhere that creatives find the critical ingredients for the mysterious alchemy that is art. It may be as simple as an abundance of cheap space. Abandoned warehouses with square-footage to rent at rock-bottom prices. Inner-city housing emptying-out as its former occupants head for the suburbs.

Most of the people filling these cheap spaces will be poor people of colour, but among the racially downtrodden and friendless immigrant will also be found the artists. And out of these unplanned social combinations, these random assemblies, the sparks of creativity fly upward.

Perhaps the creativity is inspired by the new proximity of cultures previously unencountered. Maybe it’s the novel experience of poverty. The solidarity of the marginalised. Whatever the explanation, new and exciting arrangements of images, sounds and words begin to emerge – like pearls from these gritty oyster neighbourhoods.

The impresarios of artistic production – the record producers, gallery-owners, theatre managers, content-hungry publishers – may be the first to notice, the first to profit. But what they are both responding to and encouraging are the audiences that effective art invariably attracts. Creative communities are only able to thrive and grow when they are noticed.

But, when that happens, the effects can be spectacular. Down through the ages, historians have described the special quality of those special city “quarters” frequented by artists, university students, ne’er-do-wells , prostitutes and outright criminals – the people to whom the Nineteenth Century gave the name “Bohemians”. All of the world’s great cities, from Paris to New York, have these Bohemian haunts, and all of them would be the poorer if the “buzz” and the “vibe” of their creative communities were absent.

Because they’re magnets: huge and immensely powerful magnets; attracting not only real and aspiring artists of every kind, but also those who like to luxuriate in their creative glow. The Dunedin Sound not only transformed its cold and dreary host-city into a Neo-Gothic playground for musicians with a fondness for jangly guitars and mumbled vocals, but also for poets, painters, graphic artists and the punk publishers of fanzines.

The thousands of university students who listened to the artists of their adopted city on Radio One, and who thronged to the bars and concert venues where they performed, would in just a few years become the Dunedin Sound’s greatest evangelists – New Zealand’s current Finance Minister, Grant Robertson, among them.

The problem was, by the time its local politicians grasped the importance of Dunedin’s home-grown artistic movement, which, in its hey-day, had elevated the city to the same level of brand awareness as made-over Glasgow – Scotland’s post-modern urban showcase – the Dunedin Sound had made the transition from hip to history.

It’s a lesson which New Zealand’s artistic community earnestly wishes the present government would learn. That art is not simply important for its own sake, but for the powerful contribution it can make to the reputation, cultural vitality and economic growth of the places where it flourishes. Not only does like attract like, but burgeoning artistic communities are also apt to attract entrepreneurs eager to turn all that creative energy into hard cold cash. Just like all the others, the creative industries require infrastructure. Cheap warehouse studios become expensive studio apartments.

Crass commercialism wasn’t always the prime motivation of our political class’s support of the arts. In New Zealand, state support was a socialist objective long before it became a capitalist fetish. The Labour Prime Minister, Peter Fraser, threw his political weight behind the creation of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and set up the New Zealand Literary Fund.

Partly, this was because Fraser understood that if, in a country the size of New Zealand in the 1940s, the state didn’t get in behind its musicians and writers, then nobody would. But, that wasn’t the only reason for the Labour Party’s support for the arts. As democratic socialists, they were determined that working-class people should have as ready access to the cultural production of their nation as the bourgeoisie. Why should the appreciation of Beethoven and Mozart be limited to the elites?

To political and economic equality, the pre-1984 Labour Party was determined to add cultural equality. Nation-building wasn’t just about erecting hospitals, schools and hydro-electric schemes, it was about resourcing New Zealand’s artists to create and shape the development of a unique national character. Labour used to believe as fervently in fostering a robustly egalitarian New Zealand culture, as it now believes in advancing the indigenous Māori culture.

While there are powerful arguments for redressing the historical under-funding of Māori cultural endeavour, there are equally powerful arguments for supporting the creation of a broad New Zealand culture reflective of all its many peoples and their experiences. Bureaucracy may never be equal to the sort of fleeting cultural moment that produced the Dunedin Sound, but, without intelligent state support, the emergence of a New Zealand voice will continue to be an aspiration rather than an accomplishment.

*Chris Trotter has been writing and commenting professionally about New Zealand politics for more than 30 years. He writes a weekly column for interest.co.nz. His work may also be found at http://bowalleyroad.blogspot.com.

22 Comments

Nation building is much more than that too, but essentially don't disagree as the creative communities are often extremely good a challenging the status quo, challenging the accepted 'conventional wisdom' and being able to look at the world with a different lens. But in a PC world sometimes too many people are made uncomfortable when their comfortable paradigms, and perhaps privilege, are challenged.

Go back to my old German friend who opined New Zealand just needs to jump out of its own shadow. This was in the early 80’s and then of course quite a bit of shadow was still hanging over from the old country, Great Britain, its traditions, influences and expectations. Even so, it is not unreasonable to suggest, in many aspects today, New Zealand has still not realised its own identity and that in turn often can give rise to imitation and platitudes. There is nothing to gain in being unnatural.

Too hard. There is the shadow of colonisation, and now the redress via forced integration of what purports to be Maori culture, into the demographic majority groups. Imposition of culture from top down has a limited shelf life, and we will struggle until we abandon this experiment and let it evolve organically.

Agree. Forced acculturation will gather resentment and polarization. Better to just let the melting pot simmer on its own without having it shoved down your throat.

Agree. Every culture is overshadowed by its past. These shadows are invariably due to ills committed by powers on others. Just recently I had the privilege of being able to talk to a German exchange student, and again realised that modern German youth still feel the weight of the ills committed by the nazi's. It took some discussion to convince him that we realise that it wasn't his generation, or even his parents generation who did those deeds. But that for the future to be better we must learn from our past. We cannot undo the sins of our fathers, nor can we compensate for them. Those who choose to hold too strongly to the past will be scarred for that, and ultimately will find themselves committing similar ills on others to compensate. That is not justice. The way forward can only be by ensuring EVERYONE gets a fair chance at life, good opportunities that are not leaned over by an elite privileged class. This is something that it seems the politicians and the emerging elite classes are determined to deny them.

""Maybe it’s the novel experience of poverty."". This gives the game away - except for a few outliers artistic revolutions are created by the middle class.

The dead hand of govt bureaucracy does a praiseworthy job in preserving existing art and note especially the art forms most beloved by the upper class: orchestras, ballet and fine art. But for new art take students from wealthy families and put them into an unaccustomed squalor and if you are lucky something will emerge.

""Maybe it’s the novel experience of poverty."". This gives the game away - except for a few outliers artistic revolutions are created by the middle class.

Not sure what you mean by this. Andy Warhol was obviously critical in pop art. His formative years were defined by grinding poverty in Pittsburgh. He was a hard worker and had to balance his own personal endeavors with commercial advertising before he was able to focus solely on the former.

The thing about Warhol is that there was no govt grants available to him. He had no choice but to take risks on his own.

Chris talks about the Dunedin music world. Important to remember that many of those bands were creating at a time when the property frenzy was in its infancy or before it even emerged. Warehouse space in Dunedin was easy to come by.

Things change. Good early friend of Warhols. wealthy Gunter Sachs, thought to organise an exhibition for him, Hamburg 1972. Problem was Warhol then was relatively unknown. Nothing was purchased. Out of embarrassment Sachs studiously, clandestinely purchased the lot and put all the artwork away in storage. Guess who came out a winner.

Things change. Good early friend of Warhols. wealthy Gunter Sachs, thought to organise an exhibition for him, Hamburg 1972. Problem was Warhol then was relatively unknown. Nothing was purchased. Out of embarrassment Sachs studiously, clandestinely purchased the lot and put all the artwork away in storage. Guess who came out a winner.

Right. I guess the point that the 'middle class' determines what is of commercial value has some merit. Warhol himself was actually good at self-promotion and understood the commercial world to some degree. Part of why he is interesting is that he was curious about consumer culture as a representation of art.

Interesting info about Warhol. My interest is Jazz and almost all the American greats came from middle class families but there is always the exception (Louis Armstrong). Just as Woody Guthrie came from wealth and sung against poverty so did many of the British groups from the sixties. The Beatles were working class but those rebellious Stones and many others were middle class or as we said then, they were posh.

Britain and Europe poured govt money into the arts. Not just the democracies but also the Communists and Hitler. Meanwhile the two new significant art forms of the 20th century were Jazz and Films and both evolved in the USA without govt subsidy.

My interest is Jazz and almost all the American greats came from middle class families but there is always the exception (Louis Armstrong).

Interestingly, Miles Davis came from an affluent family. John Coltrane was from a working class family, but not desperately poor, like many African Americans in the South.

Ellington the son of the White house butler. How do you define class when society is segregated by skin-colour? Tatum's family had a piano and could afford eye operations, etc. American rural blues was working class and the blues musicians were looked down on by jazz musicians. Armstrong was an inspiring miracle - proof that multiple disadvantages can be overcome. Certainly, the US govt did not sponsor jazz while it was being invented.

Call me a philistine CT, but my starting point is that "the state" (ie taxpayers' dollars) shouldn't spend a cent on arts, or for that matter sport, beyond a solid exposure to both through schooling. There are plenty of essentials, education, health, policing etc., which need the bulk of taxpayer attention.

To suggest that we would then become an artistic desert is a doleful attitude towards humans' ability to express their ideas through art (or sport) without handouts from Nanny State.

Govt support for the arts should be via funds for museums. I'd hate to see the Auckland Town Hall disappear.

But we spend millions on sports and very little on arts. As a ratepayer I am forced to spend money on a stadium in Christchurch I which I will never ever use in my life but my daughter with a full scholarship on merit for a world top school in arts in the US and pretty much guaranteed employment as a result, cannot get any funding for the very expensive accommodation and flights.

Is it state support thats required or just for the state to get out of the way - I am pretty sure that those who started Radio Hauraki in the days of a state monopoly on broadcasting just wanted the state to stop trying to shut them down.

and the same argument could be used for cafe's and restaurants that wanted to stay open past 6pm or serve wine with a meal. State restrictions that negatively impacted on the cafe culture we take for granted today

For a moment there I thought Trotter was advocating that art happens when the government gets out of the way. Because that is the conclusion from the evidence he identified. Dunedin Sound, etc

But alas. He goes on to advocate the government fund things people themselves would not. It would be better for arts, and sport for that matter, that government just stayed away. Non professionals make a better scene anyway.

Our universal government problem.

Why do we always expect the state to intervene in everything? The state is more often the problem, not the solution. Just look at the carnage the current lot are leaving in their wake.

The solution to many of todays woes are getting families to stick together, preferably with two parents [a mother & a father is ideal] & setting tax laws in place to encourage that. Most of our mental health issues would disappear if we could get our children into functioning families - as it's here that most of life's better values [& morals] are taught & learned.

It worked for more than 5,000 years up until about 50 years ago!

Art for our sake

Great headline - I couldn't agree more. We all benefit from a strong creative sector.

It's one of the reasons I support a UBI - it gives me hope that the painters, inventors, film makers, dancers, musicians, writers and historians might more comfortably pursue their talent to the benefit of all.

As a totally unartistic individual, I am in awe of those with the ability to bring joy to our senses.

A perspective from someone trying to produce an art exhibition. I spent lockdown creating what I thought, was an important story about Christchurch's Regeneration: a unique cross between photo journalism and art.

I discovered that as an 'ordinary' NZer I didn't qualify for funding assistance from CreativeNZ or anywhere else it seemed. I went ahead and funded 30 large print works myself. I converted my (closed) photography laboratory workshop, into an effective temporary gallery space. I then tried and failed to get some funding to promote the exhibition. It seemed unlikely I could reach my audience. I almost gave up entirely.

So perhaps artists don't need much funding for creating their work, as their passion will drive them to make it regardless. But they do need space to show it and help with it's promotion; to enable sufficient interest from the public. This is something that is essential for our artists. Funding of this is surely a win; both for the creator's and the community, who become exposed to a wider range of ideas and experiences.

Right now, I am hoping that the government and council websites set-up to promote the Matariki events, will provide me with a way to reach the public; notice my exhibition and come along for a look. My work is reflective; it's about loss and regrowth. It's my final try. https://instill.co.nz/exhibitions/

Arts at public expense? No.

I like arts and will pay for art work/art events which I find attractive.

Having other people pay for my interests? No.

We fund from taxpayer money sports and roads and academic studies but nor arts. Arts events you like, whatever they are, would not be possible without any training/education in arts forms but we do not fund that.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.