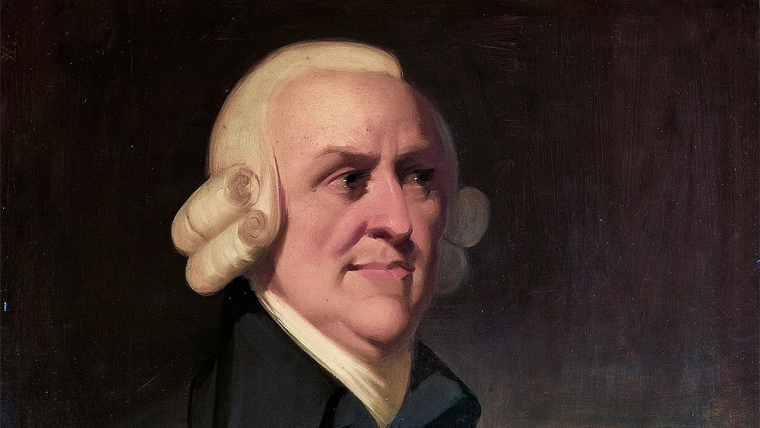

This year marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Adam Smith, the founding father of modern economics. It comes at a time when the global economy faces several daunting challenges. Inflation rates are the highest since the late 1970s. Productivity growth across the West remains sluggish or stagnant. Low- and middle-income countries are teetering on the brink of a debt crisis. Trade tensions are rising. And market concentration has increased among OECD countries.

Against this backdrop, Smith’s tercentenary is an opportunity to reflect on his invaluable insights into the dynamics of economic growth and consider whether they can help us understand the current moment.

At the heart of Smith’s theory of economic growth, outlined in the first chapter of his seminal work The Wealth of Nations, is the specialisation facilitated by the division of labour. By breaking down production into smaller tasks – a process illustrated by Smith’s famous example of the pin factory – industrialisation enabled enormous gains in productivity.

But this process is not confined to individual firms. Since the division of labour, according to Smith, is “limited by the extent of the market,” the market as a whole must expand through exchange. After all, boosting daily widget production from 100 to 10,000 is pointless if no one wants to buy widgets. So, the division of labour is a collective process that involves a continuous process of structural economic change. When there is a larger supply of affordable widgets, the widget-using sectors of the economy can expand production and reduce prices. Meanwhile, the market’s increased size would allow upstream suppliers of materials required to produce widgets to reorganise production into more specialised tasks.

As the American economist Allyn Young noted in 1928, this is a dynamic story of increasing returns. The growth process is a virtuous circle of structural change that starts slowly and then accelerates, like an avalanche. The Industrial Revolution and the rapid growth of East Asia’s “tiger” economies during the 1980s and 1990s are perfect examples of the process Smith identified. And yet the stagnant growth that has plagued developed economies over the past decade raises the question of whether global progress toward what he described as “universal opulence” has ground to a halt.

Although the division of labour into specialised tasks has often enhanced the skills and expertise of workers, this may not always be the case. The emergence of generative artificial-intelligence models has fueled concerns that employers will use these technologies to deskill human workers and cut costs, prompting calls for regulatory interventions to ensure that AI augments, rather than replaces, human capabilities.

Moreover, while economic growth since the onset of the Industrial Revolution has led to astonishing advances in health and well-being, it is important to recognise that the institutional frameworks and political choices that enabled this progress were the result of intense social struggles.

Another concern that is often overlooked stems from market size. Smith would likely have been shocked by the extent of specialisation in the twenty-first-century economy (and probably also pleased with his foresight). Today, manufacturing relies heavily on complex global production networks. Final products such as automobiles and smartphones comprise thousands of components manufactured in multiple countries. Many of the intermediate links in those supply chains are extraordinarily specialised. The Dutch company ASML, for example, is the only producer of the ultraviolet lithography machines needed to produce advanced chips, most of which are manufactured by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

But the widespread nature of this phenomenon suggests that the global market for many products can sustain only a few companies capable of achieving economies of scale. This has long been the case for large manufacturers in sectors such as aerospace, but it increasingly applies to smaller markets for intermediate components.

Consequently, Smith’s other condition for economic growth – the presence of competition – is not met. Competition helps to ensure that economic growth is socially beneficial, because it prevents firm owners from monopolising the benefits of specialisation and increased exchange. As Smith put it in The Wealth of Nations, “In general, if any branch of trade, or any division of labour, be advantageous to the public, the freer and more general the competition, it will always be the more so.”

Although the decline of competition has been a growing concern in Western economies over the past few years, the debate has largely focused on high-profile sectors within domestic markets, such as Big Tech. Policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic have responded to concentration in the tech industry with new laws, such as the European Union’s Digital Markets Act, and tougher enforcement of existing antitrust laws, such as the US Federal Trade Commission’s recent decision to block Microsoft’s takeover of Activision.

The deeper policy question, however, is whether the level of specialisation in certain markets has reached a tipping point where there is a trade-off between Smith’s two prerequisites for growth. Has the division of labour reached its limit – and is the need to enhance competition therefore another reason to diversify supply chains and develop new sources of supply of production?

Diane Coyle, Professor of Public Policy at the University of Cambridge, is the author, most recently, of Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be (Princeton University Press, 2021). This content is © Project Syndicate, 2023, and is here with permission.

7 Comments

There's no question big tech [BT] is going to get bigger in my mind. The regulation around that is always in catch up mode as BT leads us onwards, whether we like it or not. AI is an example of BT that has been going on for some time but has only recently reached mass media [& market] awareness.

Most of the good stuff gets snapped up by the military industrial complex before the rest of us are even aware it is going on, as it's in the war environment [which is a constant thing] that real advances are trialled & tested. We are watching something similar play out in the Ukraine at present. Israel's rise over the past 20 years also has this as its base.

Adan Smith was a thinker & a market developer and influenced many people over the 200 years since he wrote Wealth of Nations. It's even more astonishing when you think about how much has been developed over that time. Even the CCP used it. The competitive free market is still today the best system to underwrite wealth, health & well being for the many, even though those who cannot, or will not, partake in its many benefits constantly decry its short-comings.

I would rather be a poor person in a rich society than a rich person in a poor one. Sadly, many do not & will not understand this. I have been fortunate to have been to many places over the years & I learned very quickly how bad, bad really can be. When you know this you can then work out how good, good really is. And right here in NZ today is still pretty good, even though over the last 5 years or so, we are doing our level best to stuff it up.

Right on John!

NZ is still one of the best lands to live. Don't tell everyone......

"And right here in NZ today is still pretty good" and why of the many places I could have settled, I chose New Zealand. But...

"Even though over the last 5 years or so, we are doing our level best to stuff it up." I'll suggest it goes back a few years before that. For me, it was perhaps 2008 was when it became apparent that we'd stuffed it up in the 5 years before that. And since then, it's just deteriorated.

Is it still the best place to be? Undoubtedly. But not for what we see about us at the moment, but for the place it will be when we've finished what we have now started; removing the 'stuffed up' bits that are holding us back.

It is clear that houses are not Capital and NZ tax policy is counter growth

All well and dandy if everyone is participating in the economy not just taking like a 25 yr old sitting at home all day playing computer games smoking dope. Didn't have the welfare system back then 300 yrs ago wonder what he would make of that. That there is generational dependents who have actually never put in a days work yet get paid to live. All the while when a supposedly first world country has to compete with a country who dosnt value human life. And that what the first world country is good at like producing good food certain elements within that country want to hinder or retreat food production (hence causing more supply and demand food inflation) and yet still expect first world free healthcare/education etc etc.

'his invaluable insights into the dynamics of economic growth'

a non-physics delusion that economists have doggedly stuck to for 300 years.

Including the writer.

Adam Smith's model of competition leading to a better societal result is based on assumptions that don't exist outside of theory/ideology.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.