By David Skilling*

A regular theme of these notes is the regime change underway in geopolitics, globalisation, and economic policy. Another regime change is a global demographic transition: the great contraction of the global labour supply.

Global labour markets are tightening structurally, with implications for wages, the income distribution, and business/growth models. Firms, investors, and policy-makers need to adapt to a new world, very different from the era of low cost, abundant labour supply that has prevailed over much of the past few decades.

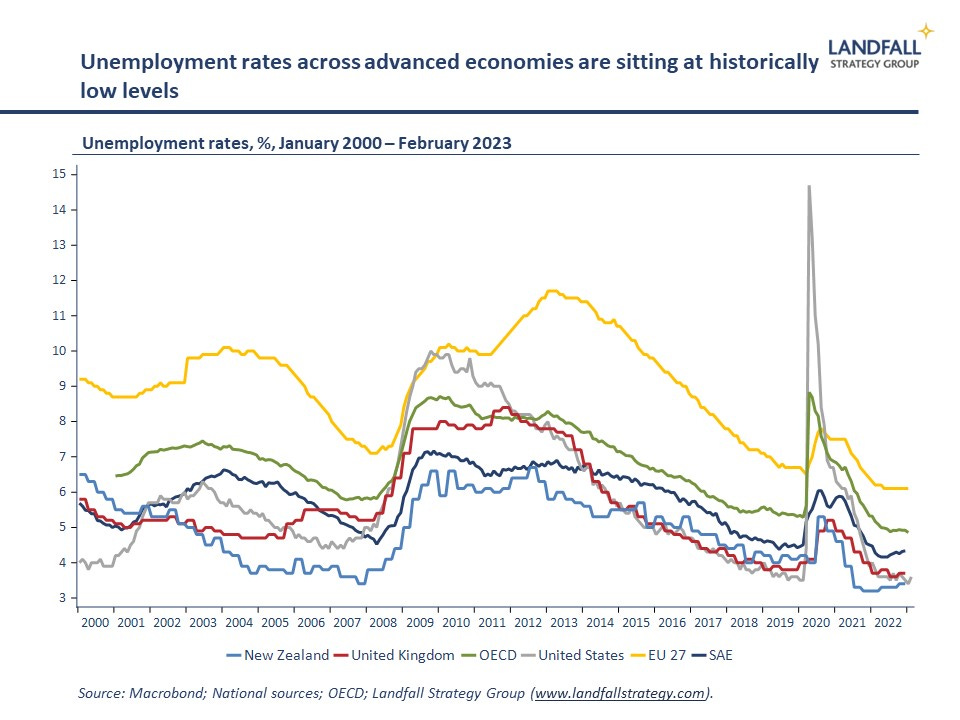

Labour markets are already tight across advanced economies. Unemployment rates sit close to record lows in the US, the UK, the EU, as well as in Australia, New Zealand, and beyond. Some of this is due to reduced participation rates after Covid, notably in the UK and the US, as some people withdrew from the labour force, voluntarily or because of sickness. There were also substantial numbers of excess deaths, although on a smaller scale than in previous pandemics. And some countries have seen reduced migration inflows.

Higher wages and flexible working arrangements will pull people back into the labour force over time. But a structural change is underway in global labour markets.

A global labour market

A big driver of disinflationary growth across advanced economies over the past few decades has been growth in the effective global labour supply: strong demographics, the integration of multiple large emerging markets (notably in Asia) into the global labour force, and rising participation rates. The headline global labour force has grown by >50% since 1990, from 2.3 billion people to ~3.5 billion today.

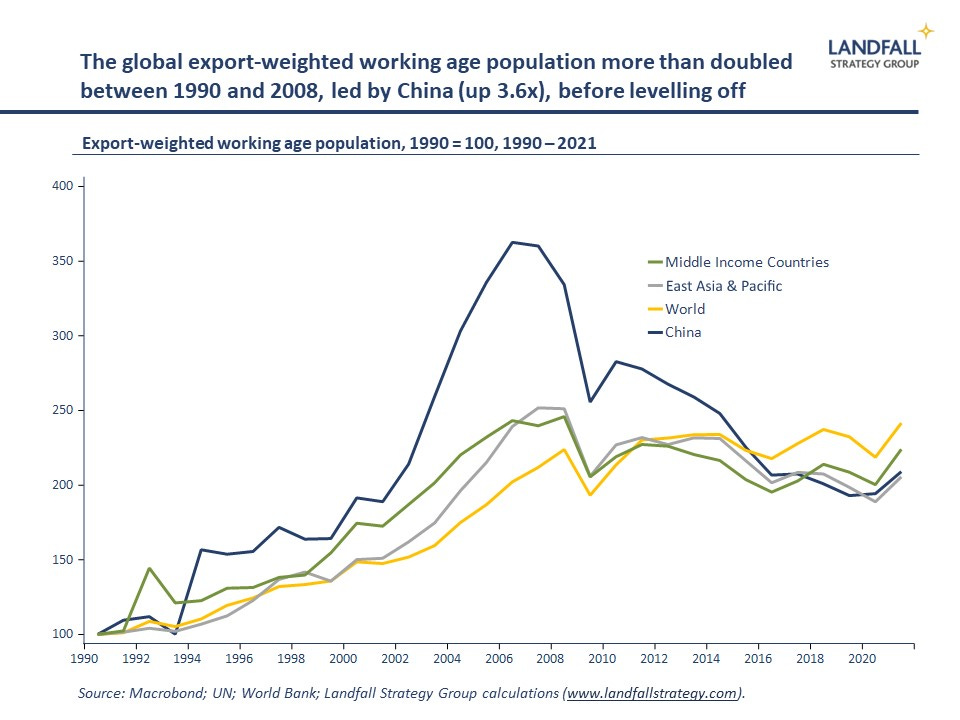

But this understates the effective growth rate in the global labour supply; intense globalisation has supported the integration of domestic labour forces into the global economy. As a rough proxy for this, I scale the labour supply for various countries and regions by their export shares. This gives an approximate sense of the extent to which workers were engaged in global activity. Between 1990 and 2008 the internationally-engaged global workforce more than doubled: from ~600 million to ~1.4 billion.

This growth was dominated by China and other East Asian countries, where strong working age population growth was combined with aggressive integration into the global economy: China’s globally engaged workforce increased by 3.6x, from ~95 million to ~340 million. Asia became the manufacturing powerhouse of the world, with workers moving out of low productivity agriculture into higher productivity manufacturing.

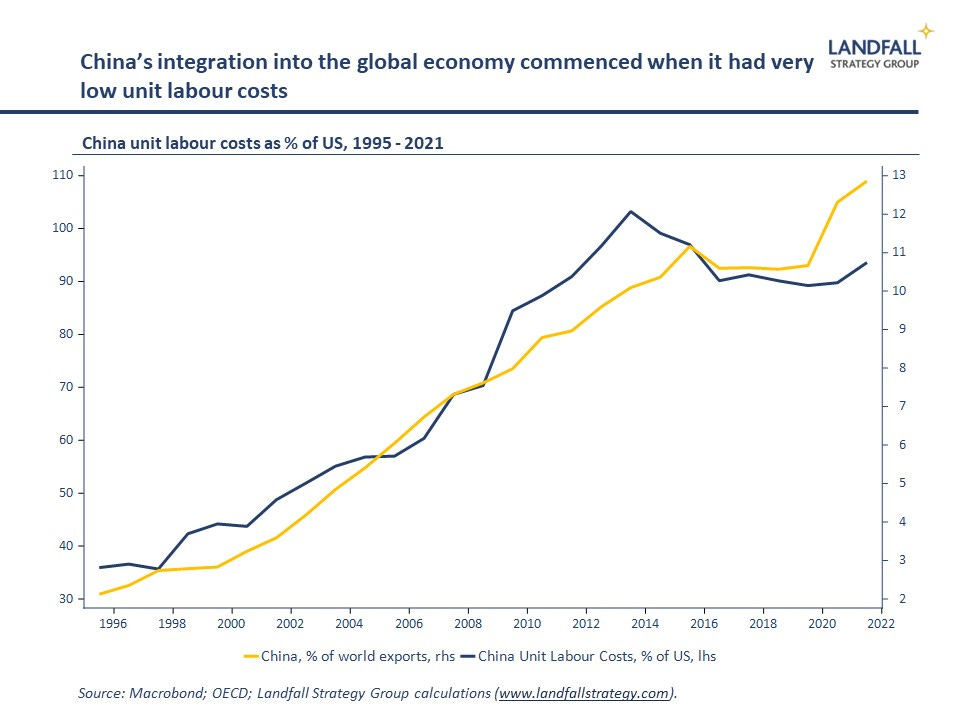

The unit labour costs of this ‘new’ workforce were much lower than in most advanced economies. Coupled with changes to labour market institutions (such as reduced unionisation), this expansion of global labour supply had big effects on wages and income distribution around the world. And these dynamics had a substantial political impact across advanced economies: exposure to import competition in the US and elsewhere has been shown to influence voting patterns (particularly in economies that haven’t managed exposure to globalisation well).

However, growth in the effective global labour force has slowed since the global financial crisis. The intensity of globalisation (world trade/GDP) has levelled off , although the share of exports from emerging markets has continued to increase. And demographic growth has slowed in some key economies.

A new (old?) world

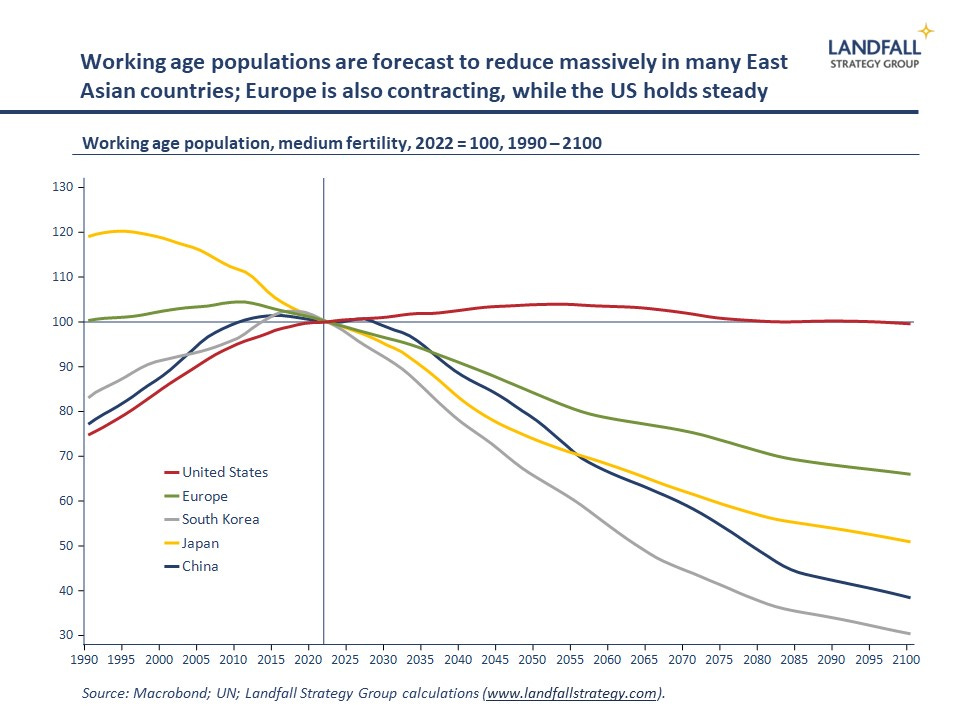

Looking forward, global labour force dynamics will change structurally over the next few decades and beyond. Demographics across many key parts of the global economy are reversing very quickly. This astonishing demographic reversal is particularly evident in Asia, a region at the centre of globalisation. The working age populations in China, Japan, and South Korea are projected to halve or more by 2100.

And by 2050, just over 25 years into the future, China’s working age population is projected to contract by >20%, Japan’s by >25%, and South Korea’s by ~35%. In absolute terms, China’s working age population is forecast to shrink from ~980 million people in 2022 to ~770 million in 2050, a reduction of ~210 million people (about the current combined total populations of Japan, the UK, and the Netherlands!). And these projections use the UN’s ‘medium fertility’ assumption, which are likely to be optimistic: fertility rates are dropping very quickly across Asia.

Europe is also aging, but at a slower pace: a forecast ~15% contraction in working age population by 2050 and ~30% by 2100. This may be partly offset by stronger migration inflows than in many Asian countries.

Population contractions of this scale are unprecedented, except following war, natural catastrophe, or pandemic. And the change is happening very quickly, providing less time for adjustment. These global demographic dynamics will have profound economic, social, and political consequences. Japan’s PM Kishida warned recently that Japan was ‘on the brink of social dysfunction’.

There are other parts of the world where labour supply will continue to grow strongly: parts of South East Asia, India and Bangladesh, as well as Africa. Some global economic activity will relocate to these areas with positive demographics.

However, the ability to fully relocate export-oriented production to geographies with stronger demographics is constrained in a world of reshoring and nearshoring: firms are organising supply chains closer to end consumers, many of whom are in advanced economies, both to better manage supply chains as well as to respond to political pressures. The US and the EU (as well as China and others) are setting policy to strengthen their industrial bases in a world of strategic geopolitical competition.

This means that there will be some ongoing bias towards production in countries with labour constraints on production. Even the US, which has the most positive demographics of the large advanced economies, is struggling to secure the labour needed to strengthen its industrial base (semiconductor plants, green energy). These structurally tight labour markets will continue for both demographic and political reasons.

The productivity imperative

This persistent, material tightness in global labour markets means that firms and countries will need to find ways of raising labour productivity to compensate.

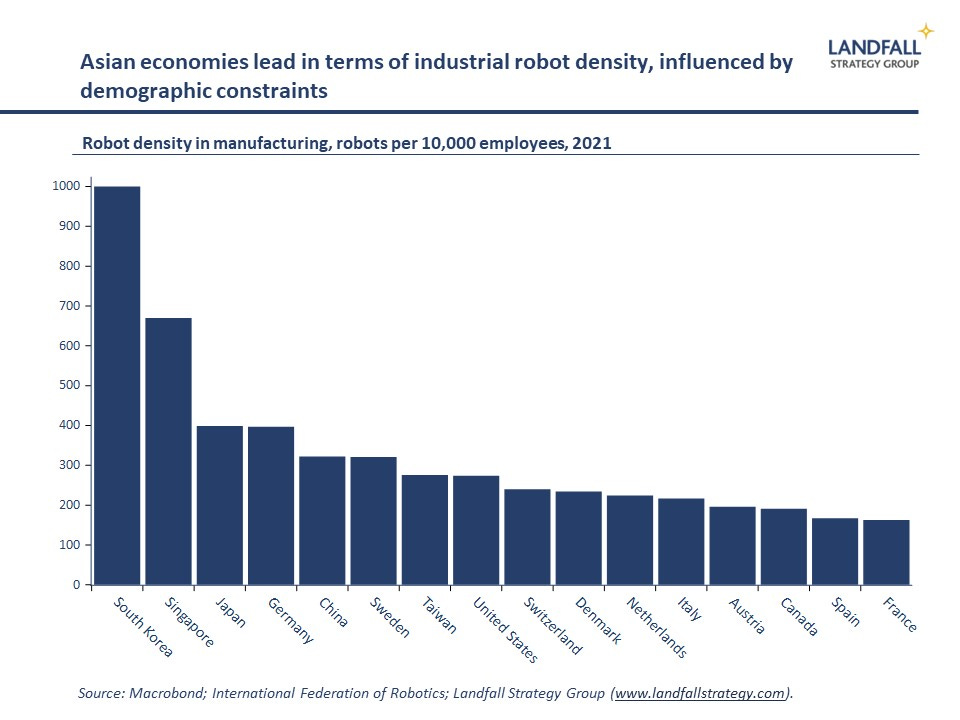

Technologies like automation and AI will provide a partial offset. It is no coincidence that rates of industrial automation are highest in countries that have rapidly aging populations; most notably in East Asia. South Korea, Singapore, Japan, and China have particularly high rates of automation – and some of this is moving beyond industrial uses into other domains, such as healthcare. This process is likely to accelerate. And Goldman Sachs analysis out this week estimated that 18% of global work could be automated by AI, with ~15% in China and ~25% in Japan and Singapore.

There are some lessons from small advanced economies in terms of how to mange tight labour markets: combining high levels of capital intensity and innovation with heavy investment in skills and active labour market policy. This supports high employment rates in these economies.

Migration at scale is another possible response. If there are constraints on production moving to countries with more labour, then labour may move to economies with excess demand for labour, such as the US and Europe. Indeed, Japan has become (slightly) more liberal in its approach to migration as it faces a contracting working age population. However, the challenging politics of migration will mean that this is only a partial solution. And what is likely to be an intense global ‘war for talent’ means that not every country will be able to attract the labour it wants.

Demography as destiny?

The increase in the effective global labour supply that has supported deflationary global growth over the past few decades will weaken and unwind over the coming several decades. The materiality of these global dynamics will have disruptive effects: on wages and the income distribution, on growth and inflation, and on the ability of countries to compete effectively. It will also shape geopolitical competition, with US demographics much stronger than those in China.

However, some of these effects may be counter-intuitive. For example, the disruptive labour-saving properties of new technologies may advantage some economies with contracting working age populations: they are under less economic and political pressure to structure their growth models to generate substantial numbers of new jobs. Indeed, the traditional jobs generating sectors (export oriented manufacturing) will likely be able to create fewer jobs in the future (‘premature deindustrialisation’), creating challenges for countries in South Asia and Africa with strong forecast demographics.

These are multi-decade dynamics, but demographic effects are already in evidence: wages are increasing, there is increasing demand for automation, and firms are relocating supply chains in response to expected changes in labour availability. Indeed, working age populations are already contracting in China, Japan, and South Korea.

Countries and firms that can position themselves for this environment will prosper – just as those firms and economies that established growth models that leveraged the globalisation of labour markets did from the 1990s.

If you have not already, you can subscribe for free to receive occasional public notes - or take out a paid subscription for full access to these notes:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

41 Comments

Great article - finally highlighting what I believe will be one of the mega drivers for this century across all sectors.

Absolutely agree. Within the OECD the number of working people peaked in 2018 at just over 600m and has fallen by 20m people per year subsequently.

My hope was that Covid-19 contributed to that and we would see a bounce but it seems now many have actually hung up their clogs for good. The company you work for now may employ as many people as it ever will.

That's a great read, thanks David.

Will NZ return to relatively easy migration inflows to fill demographic driven labour shortages?

My gut feeling is that we have to.

Ahead of that potential flood of immigrants NZ must invest in infrastructure capacity (roads, schools, housing, 3 waters, health services, energy, etc) to anticipate growth in demand on the infrastructure. A repeat of the last 20 years is untenable.

NZ has done this in the past, particularly for a period post World War 2. This was achieved by State organisations like the Ministry of Works, ECNZ, Department of Education, Department of Health. in the 1960s NZ had one of the highest standards of living in the developed world.

Apparently that was too inefficient and private sector would do a more efficient job of this. But private sector, of necessity, must be preoccupied with short term (5-10 years) profitability, rather than long term (30-50 years) provision of accessible capacity (over capacity in the short to medium term).

If NZ is to avoid a repeated housing crisis, then the State, and I don't care what colour that comes in, must put in place the massive capital investment to provide the infrastructure for the future. Playing catchup delivers disastrous social outcomes, as has been the lived experience for many over recent decades.

The consequences of not acting with a 50 year vision, I reckon will see a steady decline in the standards of living for most people living in NZ. And there will be no way that social and environmental targets can be anywhere near met.

Implementing a tax on capital surely has to provide a more equitable means of funding such necessary development.

in the 1960s NZ had one of the highest standards of living in the developed world.

People love this stat, but it masks the context that most of the competition spent nearly a decade in war and then nearly another decade re-building and recovering from it.

Maybe everyone should support Putin and we'll get back to our rightful place as "a nice place to watch the world beat the crap out of itself".

Immigration doesn't fix anything unfortunately, it just defers the problem.In addition many of the developing countries New Zealand sources immigrants from, like China and India, themselves have birthrates under the replacement.

There is no easy fix but trying to increase the birthrate in New Zealand would be a very good start.

Squishy - then what? OH, that's right, more people. Then what? Oh, that's right, even more people.

That on a planet which is already 6-7 billion overshot in long-term-maintainable terms.

Madness; totally illogical.

Wasn't it the Babylonians that were freaking out at 25 million people?

They collapsed.

Outran their resource/energy base.

We're doing it globally, for the first and only possible time. Almost 20 years ago, I was at a physics/energy lecture (Otago Uni) where it was pointed out that there won't be enough energy for a re-boot.

As I said: madness.

Can't help but feel you missed the drift.

We don't know the limit, and the limit keeps getting surpassed despite a constant protest through the ages otherwise.

It's a very rare thing for a doomsayer to accurately predict much other than their own neurosis.

Limit isnt some kind of wall, you can massively overshoot a limit if your juicing off millions of years of banked energy.

However you want to slice it, it's a made up guess assumption.

First problem is using a raw body count, because there's almost a 20x difference in energy footprint between the first and 3rd world.

No, it ain't.

Life - all forms thereof - is a state of being in positive EROEI territory. Yes, you can go negative for a short while; you lose body-fat, then muscle, then die. Globally, societies are demonstrating negativity; decaying infrastructure, reduced spending power; exponential increase in labour demand (an unwitting attempt to assuage energy depletion).

The problem is that - as the post immediately above says - we inherited an accumulated stock of historic solar energy. And applied it to food-production. And multiplied our population exponentially; 1 billion to 8 billion within 200 years.

Ecologists will tell you this is classic species overshoot - which is ALWAYS followed by collapse to BELOW the sustainable level, usually - but not always - followed by oscillatory recovery. My last op/ed here, has a graph with three very obvious inflection-points, all happening NOW. Your 'body count' is a valid count - as is the energy requirement per head. Unfortunately, the finite-and-depleting nature of the energy resource happening is faster than demographics, and 8 billion ex fossil energy are living, on average, at a level BELOW the Australian Aboriginal level pre European intrusion. We'd have to be down to 1-2 billion, to have a chance of doing better.

People keep calling it, putting lines on graphs and thinking they are somehow omnipresent, but things seem to keep going.

It's fairly clear urbanisation is and will create depopulation on a massive scale. This will contribute to failing infrastructure, but also a stabilisation of humans' seemingly insatiable appetite for the planet and it's resources.

Or it won't, and it's back to caves and clubs for us.

"Will NZ return to relatively easy migration inflows to fill demographic driven labour shortages?"

Most countries in the world are already trying this.

"Ahead of that potential flood of immigrants NZ must invest in infrastructure capacity (roads, schools, housing, 3 waters, health services, energy, etc) to anticipate growth in demand on the infrastructure."

We are always/already behind in NZ when it comes to infrastructure and if we are short on labour now...

LouB, I think you are overlooking quite a bit. The 1960's (and earlier) were hardly our "finest hour ". Certainly as you say our state organizations were spending up large on perhaps essential infrastructure, but the other side of the coin was import licensing, fixed exchange rates, tight limits on foreign travel expenditure, and general criticism of both major parties for their "borrow & hope" economic policies.

Governments understood the long term difficulties associated with our heavy reliance on primary produce and attempts to diversify were a constant promise at election time. However, we came up with some bizarre solutions like the once burgeoning car assembly plants, or our Waihi tv production. (I remember paying $1000 for a 12 inch colour set in the 60's) These and similar industries required large state house construction to accommodate the immigrants we encouraged to man these new industries....industries utterly uneconomic from a global perspective and doomed to wither when we finally opened up to the world.(reality )

You may not be wrong about a current need to upgrade much of our basic infrastructure but before we get too carried away with second harbour bridges/light rail/better roads, schools and hospitals, it should be noted that such will require considerable increases in the importing of steel, concrete, tar, etc., etc.,....which will have to be paid for in "real" currency....stuff that is not just printed out the back of the Beehive. And at the moment we have a record foreign exchange deficit!

Yes, it's been a wonky ride all right.

I too am concerned about the BoP deficit.

If NZ was a private home, or old school family farm, facing a deficit like we have, there would be a heap of belt tightening.

I can't see the agricultural sector rescuing the economy this time round.

There have been a lot of innovations over the last 30 years, particularly in the digital field....but they mostly get sold or relocate offshore.

What is the percentage of the NZ productive economy that is offshore owned? That state of affairs seems to leave NZ with the 0% fat skimmed milk and none of the cream.

Unsustainable

So the next famine is that of people.

What governments should be encouraging is mum, dad and 3 kid families.

But they won't, and we'll go the way of Japan etc.

Theyve been trying to do this for 20 years.

It's called "working for families".

Incentivising childbirth hasn't caused a marked lasting improvement in birth rates anywhere its been implemented.

Perhaps because the debasement of fiat currencies have financially ended the idealistic view of having a family and a home where the kids can safely spend time outside.

There's a fairly strong body of evidence supporting non-fiscal drivers being of much significant impact.

Neil21 - NO, IT IS NOT. 100% NOT.

That approach ignores the real world (as economics does). It ends up with people standing shoulder-to-shoulder, having displaced all other biology.

Obviously that is undesirable, besides being unattainable in biological/physical terms.

The population of the planet has grown exponentially, via resource draw-down. That arrangement is temporary, by definition. Ading MORE at this point, is not just illogical, it's madness.

How can such ignorance still exist?

Great article. There would be some enormous benefits realised for countries that have a static or slowly declining population:

- Costly infrastructure investment could almost stop, all you would need to do is provide a maintenance budgeting.

- You could close down polluting power plants and factories as a priority so greatly improve your environmental performance with no capital outlay.

- You can density you population in urban centres increasing per capita incomes.

- You can cut expensive welfare programs as unemployment will be perpetually low.

In many ways I would say when we look back at this period we will note; "more population growth, more problems."

Let's say the quiet part out loud.

Our relationship with China is one of the most intricate and important. How we manage it will be a determining factor for our future economic prosperity and national security Link

The #EU side talks a lot about de-risking recently. If there is any risk, it is the risk of linking trade with ideology and national security and creating bloc confrontation. China is ready to work with the EU side to reject decoupling and promote global prosperity.(photo:AP) Link

The problem for China is they have built their economy on labour, their transformation isn’t far enough along that they can become a Japan. Repressive rules will work against any effort to foster a knowledge economy. And they can’t import the labour they need, which country has the surplus labour at the volumes China needs when every country outside of Africa is seeing low population growth? And what rights or incentives would being those migrants to China? China is in big trouble, it may take a decade for the seriousness of the problem to become obvious but it will in time.

In 10 years, as these issues become evident, I expect immigration policy to shift from how do we keep them out to how do we get them in as countries compete intensely for a shrinking pool of migrants. This is only a bridge though, as some point AI and robots will take over and human labour will be less important. I know people say technology always generates new jobs but that isn’t going to be the case with AGI.

Even in Africa fertility rates are rapidly declining.

There will be a war for talented immigrants, you can already see in New Zealand the government keep lowering the bar on requirements to apply. At this rate a heartbeat will get you in as a skilled migrant.

Good article and comments.

Shrinking populations that can afford our expensive food is going to be a big deal for NZ. Balance of payments is already crap, and problems sourcing fertilizer eg. Phosphate, are building. It is going to be quite a mindset adjustment to live in a world where the solution to most problems is no longer to just try and increase exports.

Guess the problem solves itself? If our population shrinks, a shrinking market we sell into kind of isn't such an issue. It's only yeasty growthists that see living within planetary boundaries as something to be avoided.

It;s a thought-provoking article, but 'good"?

Yeah nah.

It's all about energy; labour is mere noise compared to fossil energy (which economists don't count). Productivity, in fossil energy terms, is energy efficiencies. They are, entirely predictably, plateauing and EROEI is rendering a reversal of net energy available across the planet. It doesn't take much of that reversal, to demand s---loads of labour in attempted displacement.

Compounding that, entropy. Compounding that, complexity (too much thereof).

In physical terms, we will simplify, reduce and triage. We have no choice. The demand on labour will still increase, exponentially and well beyond any supply capability - we are, after all, headed for peasantry.

The bigger question is what happens to trading, and our (already overdrawn) trading-tokens?

It's all about energy

Isn't it all really vibrations in waves?

Great article. Besides the labour supply, consumerism ties to young people closely as well.

The irony is that we don't have enough labour, at the same time we have too much Labour!

I am counting on AI to make up the shortfall, particularly in hospitality, nursing and the service industry generally. No panic.

What's your point?

AI will replace thousands of workers by taking over repetitive tasks. It’s a given and happening everywhere. Hence we will no longer need increased migration.

Those are 3 industries technology will supplant later than sooner.

It was just a joke re their pen-name.

But technological complexity never survives societal collapse

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/477.Collapse_of_Complex_Societies

Its obvious we should all just live without all the china made crap we don't need. Make stuff cost enough for people to value it. Clothes have got so cheap we all throw out perfectly good condition items every yr. Fridges are replaced every 4 yrs as they breakdown just out of warranty and they are not worthwhile to fix....yet we had the same fridge our entire childhood in the 80's. Put an oak chest of drawers on trade me that's 50 yrs old and will likely last another 100 and no one will bid on it. Put a cheap but modern looking thing from kmart it sells within minutes. Made from formica it will not survive a coffee being spilt on it and will be in the landfill within a yr and requiring a factory in China to make us another. Pass laws that minimise waste-make things standardised so companies can't release endless one off special designs slightly differing from previous items so that when it breaks there no replacement parts or matching ones available. Ban cheap plastic things like the toys inside Christmas crackers- what a waste of human labour energy making those things is. And OMG increasing the number of humans on the planet has got to be the stupidest idea any person could possibly have. Period.

The problem is price is how people inherently determine value.

Yes, and trace that to its logical origin?

Combined wishes for cheaper, drives a race to offload real costs. The best way to avoid them is not to account for them; calling them 'externalities' being a classic method.

So price - in terms of being able to warn of pending issues - is a lie; a falsehood. One which politicians, economists and most of the masses, choose to believe. We are watching the rapid divergence between falsehood and truth; I am finding that more and more older people are 'getting' that they had the best of it; that things will get worse from here on in.

What was that first monologue in the Sopranos? Tony couldn't escape the feeling that he was at the end of something, rather than the middle.

Your generation is coming to the realisation that many of them spent half a century fixated on the wrong things.

It's not the MOC crap; more and more are already made in other Asian countries, like Vietnam. Meanwhile, China has started selling more complex artefacts like EVs. The biggest question is do you/we have the courage to resist western consumerism that has been around for decades?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.