By David Skilling*

Russia’s new economic friends

The UN General Assembly voted again last week to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, by a margin of 141 to 7 with 32 abstaining. However, on a GDP or population weighted basis, the margin of international support is less compelling. These differences have been on show again at this week’s G20 Foreign Ministers meeting in India.

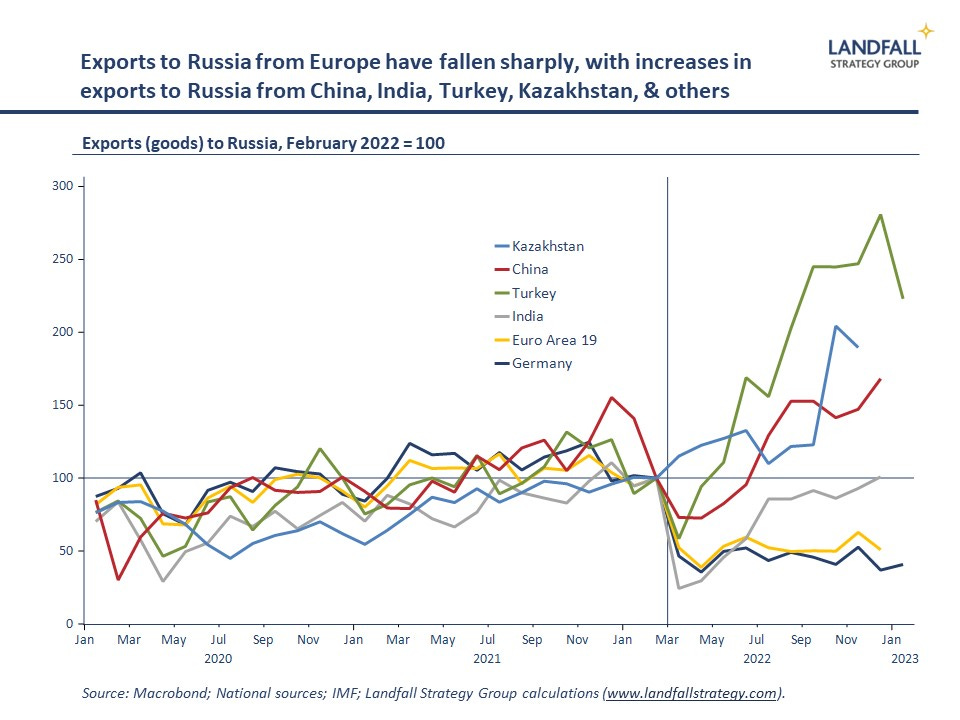

Another way to understand positioning on Ukraine, and geopolitical positioning more broadly, is ‘to follow the money’ by looking at trade patterns with Russia. Exports from Russia have been strong on high oil and gas prices. But exports to Russia have also remained relatively resilient over the past year: the IMF estimates that exports to Russia in November are down by just ~10% relative to the average over the several months prior to the invasion (recovering from an immediate drop). This is partly on the rotation of imports and exports away from economies sanctioning Russia towards other countries.

Exports to Russia from Western countries are well down over the past year, compared to before the invasion. Across the Eurozone, exports have halved with exports from countries like Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Denmark down by even more.

But Russia’s loss of these import sources has been replaced by exports from other economies: notably economies like China, India, Turkey, Kazakhstan, and the UAE. In these countries, exports to Russia are sitting at or about record levels.

The non-universality of the economic sanctions has reduced the costs that they impose on Russia, although the costs are real and growing. There is also some evidence of sanctions-busting, where Western goods are being supplied to the Russian markets through these third markets: the UAE is under increasing pressure this week from the US, the EU, and the UK.

China’s economic statecraft

China’s economy is rebounding as it opens up after its zero Covid policies. This week’s PMI numbers were stronger than expected, the fastest pace of expansion since 2012.

This recovery provides the basis for more active ‘economic statecraft’ in which China uses market access as a strategic asset. Chinese diplomacy has been increasingly active across Africa, Eurasia, and the Gulf.

This economic framing is also the context in which to assess China’s high level peace plan for the Russia/Ukraine war: it is best seen as a symbolic device to position China with countries (particularly in the global south) that simply want the war over. But unless China’s ongoing conversations with Moscow and this week’s state visit of the Belarusian President to Beijing are some sort of creative ‘Nixon in China’ move, the peace proposal is unlikely to go anywhere: Mr Xi has not spoken to Mr Zelenskyy since the invasion, and China’s peace plan is platitudinous rather than substantive.

There are also economic diplomatic efforts across Western economies: China looks to be moving to lift sanctions on a broad range of Australian exports, which it had imposed in 2020 after Australia called for an inquiry into the origins of Covid.

And the Chinese Foreign Minister and Chinese diplomats have been capital-hopping across Europe, looking to improve relations that have become particularly frosty since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Visits by the leaders of France, Italy, and the European Commission to Beijing are planned over the coming months.

However, there are limits to China’s economic statecraft. The Chinese Foreign Minister’s recent speech to the Munich Security Conference was heavy on anti-US sentiment, which did not land well. Chinese efforts to exploit US/Europe differences on economic policy (such as on the Inflation Reduction Act) and Europe’s significant economic exposure to China are undercut by China’s ongoing coziness with Russia. Europe has become more hawkish on China over the past few years – and the Russian invasion has injected caution on economic engagement with geopolitical rivals.

Adults back in the room

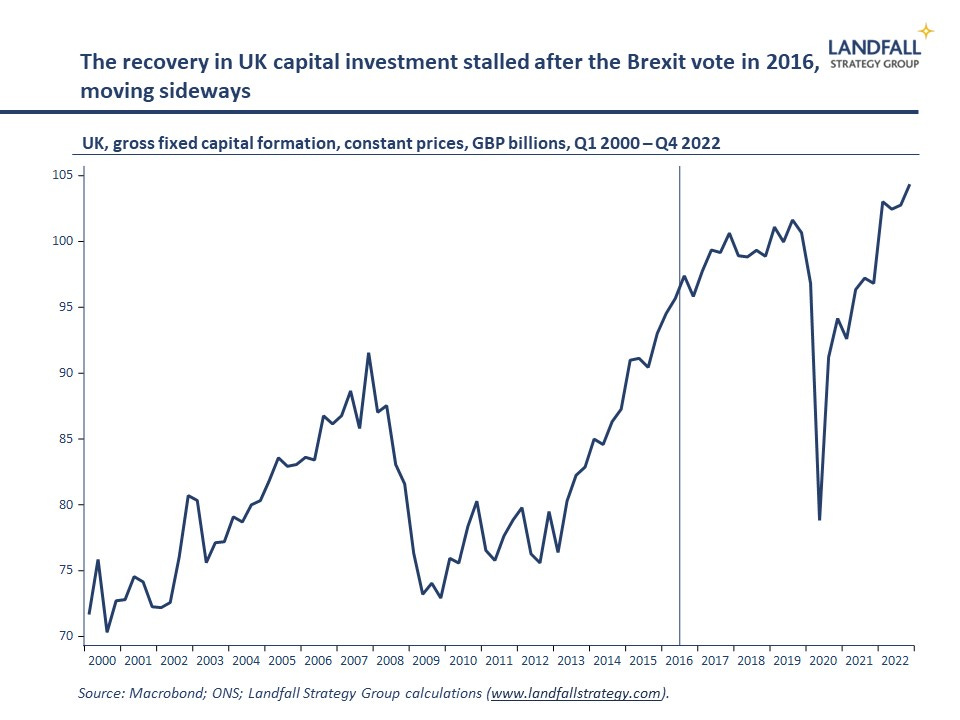

This week’s agreement between the UK and the EU on the Northern Ireland Protocol demonstrates the moderate turn in UK politics after the turbulence of Prime Ministers Johnson and Truss, supported by changing public views on Brexit. The economic importance of the ‘Windsor Agreement’ is not so much in the specifics of the deal, good though they are (particularly for Northern Ireland, where significant new inward investment is now possible).

But it creates a platform for a more constructive engagement with the EU. Already UK participation in the EU’s Horizon research and innovation programme is back on the table. And there is potential for greater collaboration on economic and security issues; being a mid-sized country apart from other groupings is not a comfortable place for the UK to be in the current global environment. The GBP rallied on improved UK sentiment.

There is still a long way to go in normalising relations with the EU, but at least the UK is not shooting itself repeatedly in the economic foot. Brexit is not the only issue constraining the UK’s economic performance – the break in the UK’s economic trajectory happened earlier – but the meaningful Brexit drag on business investment, trade, and migration since 2016 has made it much harder to strengthen the UK’s performance. The UK has been the worst performing G7 country since the pandemic.

The UK needs to apply this newfound political seriousness to its structural economic problems: raising investment and productivity, strengthening public services and infrastructure, and much else beyond. This week’s rotation to substance away from performative politics is a good first step in what will be a long journey.

Sabotage in the North Sea

Economic war is broader than physical war, and countries should be prepared against broader exposures: from cyber threats to physical attacks on energy and communications infrastructure. The global economy is knitted together by undersea cables and pipes, which creates a series of invisible exposures.

Last week, a joint report from Dutch intelligence agencies warned that Russia was covertly mapping key energy infrastructure in the North Sea (wind farms, gas pipelines) in preparation for possible acts of sabotage. A Russian ship had been detected at a Dutch offshore wind farm, which was escorted away by the Dutch navy and coastguard.

And over the past several months, Norway has stepped up military surveillance of its oil and gas facilities in the North Sea after (likely) Russian activity around key offshore infrastructure. An annual security assessment released in February said that sabotage was ‘unlikely’ this year, but there were risks to Norway’s oil and gas assets if Russia decided to escalate beyond the war with Ukraine.

There is precedent of course. The Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines were blown up (near Denmark and Sweden) in murky circumstances last year.

And communication cables continue to be the source of espionage activity. Last year, Russian ships were repeatedly sighted off the Irish coast near undersea communication cables between the US and Europe.

The extension of hybrid war to countries beyond Ukraine is not likely imminent. But these recent experiences show that attacks on critical infrastructure remain a risk that needs to be guarded against; perhaps particularly by smaller countries. Europe is beginning to take steps (including through NATO and the EU) but these risks extend much further.

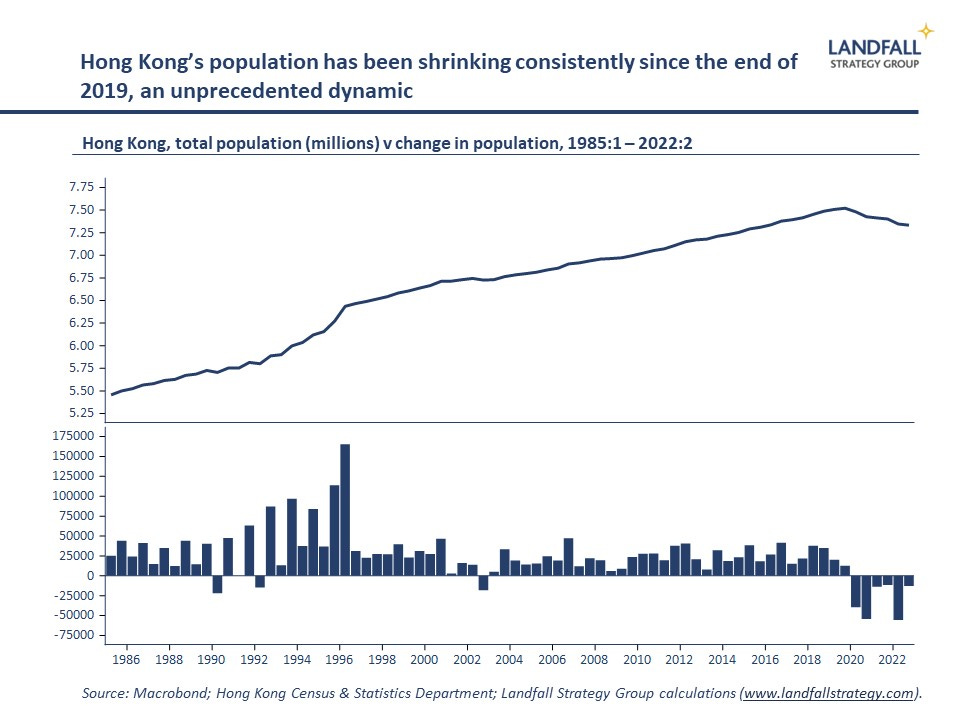

Hong Kong

Recent data shows that Hong Kong’s population continued to contract in the second half of 2022. This makes the sixth consecutive drop in population (reported every 6 months), with the population reducing by almost 200,000 to ~7.3 million since the end of 2019; a drop of ~2.6%. This is an unprecedented decline, after decades of strong population growth with only occasional drops (the last being in 2003 during the SARS outbreak).

There are several reasons: the departure of people after the 2019 protests; China’s increasingly repressive measures, and the de facto ending of ‘one country, two systems’; the direct effect of the pandemic; the distinctively stringent lockdown measures through the pandemic (Hong Kong is only this week removing its mask mandate, after 945 days…); as well as an aging population.

Many Hong Kong citizens as well as expats have voted with their feet: the UK has received >140,000 Hong Kongers under a special migration scheme. And Singapore is attracting significant flows of people and capital that are coming from Hong Kong. Indeed, Singapore’s population growth has recovered to its pre-pandemic levels.

These respective demographic trajectories between the two city states are reflected in real estate and rental prices: Singapore’s prices are soaring, while Hong Kong’s remain under downward pressure. And more broadly Hong Kong’s economic performance remains sluggish, with both domestic and external sectors under pressure. The government has announced various stimulus measures (including offering 500,000 free tickets to Hong Kong), but the political context around Hong Kong has structurally weakened its attractiveness.

Other commentary…

And in other recent commentary, I recently recorded a podcast with the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission on global issues facing New Zealand’s infrastructure sector: available here. And a background paper I prepared for the New Zealand Productivity Commission’s latest Inquiry on strengthening resilience to global supply chain disruptions was released this week. I provide an international small economy perspective on global supply chain issues, and possible policy responses. The paper is available here.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

19 Comments

The advancement and proliferation in electronic technology has created a battlefield like no other in previous history and alongside that an entirely new breed of espionage. Just think only a hundred years or so ago the British fleet at Jutland got themselves in a fine mess partly because they had not perfected their ability to signal to one another with flags. Russia now has needed to alter its strategy to destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure rather than reliance on military manoeuvres. That is hardly novel. Bomber Harris inflicted much the same on Germany WW2. What is different now though is the vulnerability of the great lengths of international cabling for communication, pipelines for energy flow and land transport. Strategic targets aplenty. Can’t imagine it’s only Russia drawing up maps of all of that though.

Yes, it would be amiss of any of the major military powers not to have up to date info on all of its potential enemies infrastructure.

Russia now has needed to alter its strategy to destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure rather than reliance on military manoeuvres.

Some Necessary Admissions From People In The Field

Ukraine outgunned 10 to 1 in massive artillery battle with Russia

A year of conflict has passed and the Russian forces have yet to attain either possession or control of any great length of territory on the east bank of the Dnieper largely because they have failed to establish, east to west a front line, not even a salient in truth, to secure the northern approaches. In WW2 both the Wehrmacht and the Red Army realised that Kharkov was strategically, the key. That is why there were four major battles for control of that city. When Russia takes Kharkov and has it under control, then I will concede they might actually be going somewhere.

You are confusing the constraints of the current SMO versus outright declared war.

Regardless of whatever war footing Russia wants to describe itself as being under, the fact remains, from history from Napoleon to Adolf, until they control the east bank of the Dnieper substantially, they cannot hope to stabilise their northern flank. Sure they may well have the means to do so, and intend to do so, and as said, when they take control of Kharkov, I would wager that they will be able to say, they have done so.

A good read. And...murky, indeed.

"The Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines were blown up (near Denmark and Sweden) in murky circumstances last year."

"Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh...claimed that the September 2022 bombing of the undersea Nord Stream gas pipelines was carried out by the US in a covert operation. The decision to damage the pipelines occurred after more than nine months of top-secret debates inside the Washington intelligence community."

Lack of mainstream media coverage of nordsteam really makes me despair.

After their Nordstream pipeline was blown why wouldn't Russia not use the same precedent?

I don't know if Hersh is correct or not but others have criticized his later writings because of his over reliance on anonymous sources.

That's a sort of non comment ngagonui.

Russia is playing a dangerous game if it sabotages infrastructure in a NATO country. The Russian and Chinese have powerful armies but their Navies are in no way comparable to NATO Navies. It would not be a stretch to say that the NATO could effectively enforce a maritime exclusion zone around Russia and China, this would be catastrophic for either/both.

Well NATO certainly have an advantage in nuke powered subs, over three to one in fact. Australia to join the club, likely Japan too. With satellite surveillance surface vessels are today a lot more vulnerable than they used to be. Subs therefore have become the critical factor.

And these are relatively cheap to make and deliver to US coastal regions.

Aye hardly worth the effort. Because if it starts up who has got what won’t matter much because there won’t be much of anything left. This is not a situation such as the naval race, Dreadnoughts etc, prior to WW1 between the Kaiser & Britain. That would, and did, just see battleships & similar at the bottom of the sea. One nuke strike from one nuke sub, from either side, has potential to wipe out numerous cities on any continent.Best not to think about it, but just hope that those in those positions of power do think about it, and seriously so.

Not sure subs would be the 'critical factor' in a blockade of China. Only under extreme circumstances would the US risk them in direct attacks on Chinese navy ships. The primary role of the US silent service remains intelligence gathering and nuclear weapons carrying deterrence platforms. Given China's economic viability and survival is so heavily dependent on its merchant fleet, which the US could render largely unusable in a matter of weeks, China's naval sabre rattling will remain localised bluster until they acquire more strategic distant naval bases from which to project a genuine naval threat.

Yes agreed, my comment was about a general situation, could have made that more clear.

Underwater drones. Navies kaput.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.