By David Skilling*

The global economy is being buffeted by shocks: from a surge in inflation and higher interest rates, to global supply chain disruptions and geopolitical conflict. Volatility in global equity markets remains elevated, reflecting substantial economic and political uncertainty. JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon this week warned investors to brace for an economic hurricane.

Some of this is the consequence of emerging from a global pandemic, as well as the near-term impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In addition, structural dynamics – from regime change in geopolitics and globalisation to the net zero transition and disruptive technologies – are leading to sustained high levels of economic volatility.

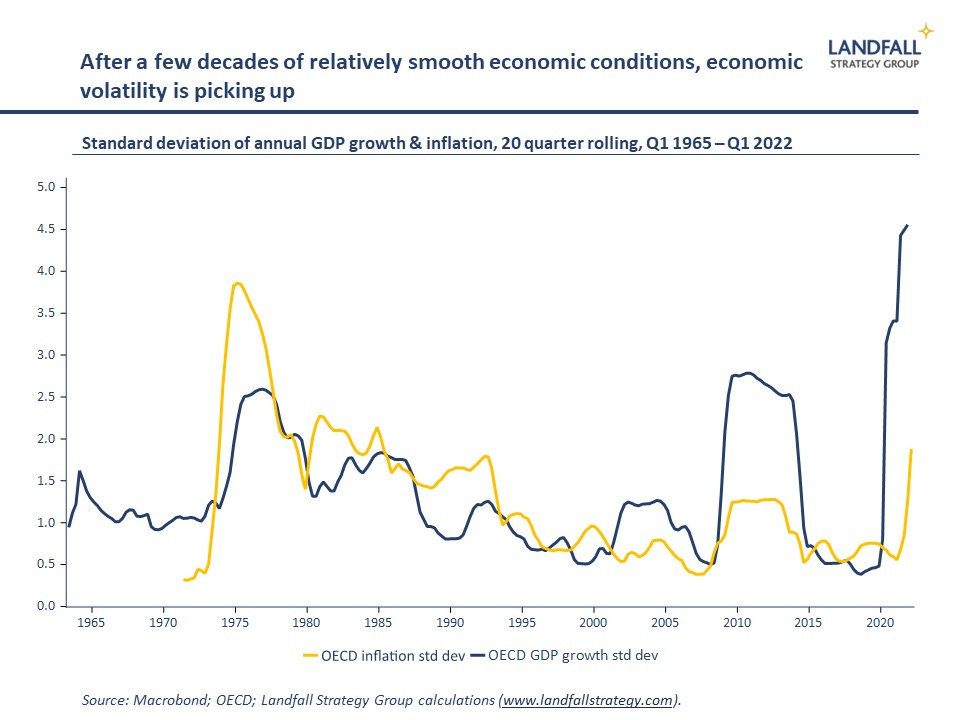

Despite being punctuated by the pandemic and the global financial crisis, the past 30 years have been a period of reasonable calm in the global business cycle. This Great Moderation is behind us, and sustained turbulence is likely as we transition to a new economic and political regime.

Great Moderation no more

‘The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters’, Antonio Gramsci

There are multiple risks that are emerging, which together will create a much more turbulent operating environment.

The intersection of higher inflation and interest rates, and the record-high public and private debt stocks, make economic and financial shocks increasingly likely. Inflation is likely to be structurally higher than over the past few decades (frictions on globalisation, the net zero transition), with consequent pressure on interest rates. Although I expect macro policy to remain broadly expansionary, business cycles will likely get shorter and choppier.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, geopolitical conflict can generate substantial economic costs. And escalating geopolitical tensions between the West and China, with the potential for major risk episodes (e.g. Taiwan), have the potential to generate even larger economic costs given the economic scale of China.

The fragmentation of the global economy due to geopolitical pressures will lead to increased costs and uncertainties. This pace and nature of this fragmentation process will be shaped by policy decision-making, from dual circulation to strategic autonomy initiatives. And as I noted last week, there are risks that political choices will worsen deglobalisation pressures – with associated costs.

The potential for domestic political events to raise the global risk profile is also increasing: economic and political management in China under President Xi; further political dysfunction in the US; and risks in countries like Russia and Turkey.

The net zero transition will transform energy, industrial, transport systems, causing disruption across the economy. New growth sectors will emerge, new low emissions ways of doing business will be developed, and substantial reallocations of capital will be required.

Alongside this, disruptive technologies are being deployed at scale – having been accelerated through the pandemic. I am still persuaded by the potential for these investments to strengthen productivity. But this process will be disruptive to labour markets and the broader economy, in a way perhaps similar to deindustrialisation.

Navigating stormy seas

‘In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if, in tempestuous seasons, they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean is flat again’, John Maynard Keynes

So we are moving into what is likely to be a more turbulent period as we transition to a new economic and political regime. There will be rapid, at-scale changes on a broad range of fronts. The 1970s are a useful analogy for this transition; a rolling series of economic, political, and policy shocks that lasted for 10-15 years.

Understanding this changing weather will be central to navigating successfully through increasingly stormy seas for firms and governments.

One of the key things about many of these economic and political risks is that they will have uneven impacts across the economy: they are commonly firm or sector-specific shocks rather than general demand-side shocks. This means that different firms/sectors/economies may have vastly different exposures: those that are emissions intensive, are exposed to China, are heavily leveraged, or that have direct exposure to disruptive technologies, are likely to be subject to more risk.

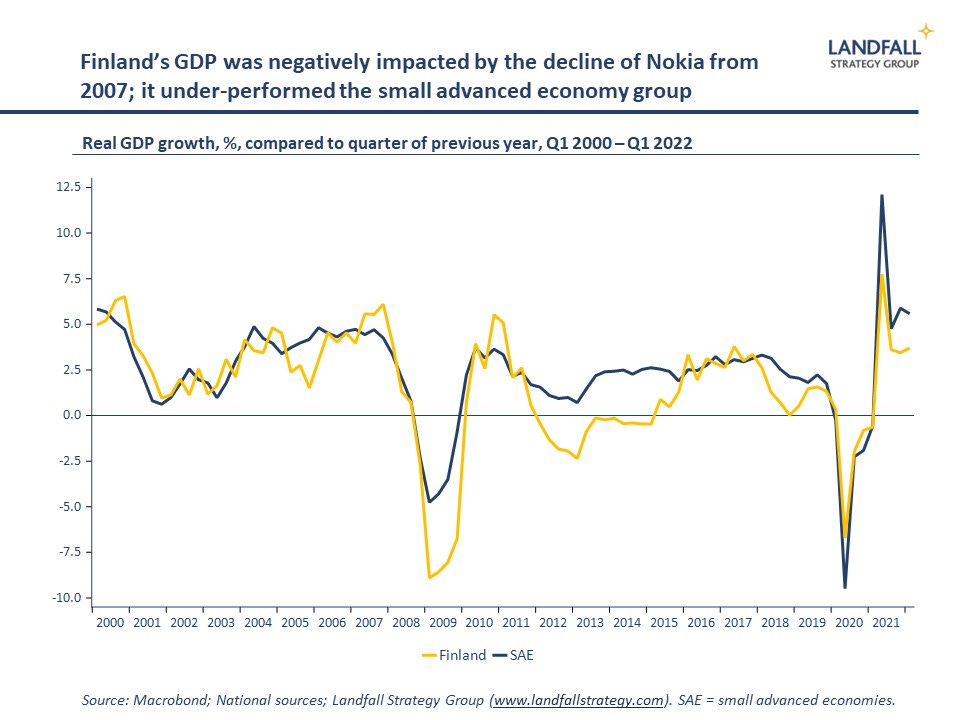

For example, this increased risk profile environment will be particularly challenging for small advanced economies, even those that are well managed and high performing. Small advanced economies have relatively concentrated economic/export structures – and so idiosyncratic shocks to important sectors or markets can have meaningful aggregate impacts.

Finland provides a salutary example: Nokia lost ~80% of its value between 2007 and 2012 as it was out-competed by Apple, leading to reduced employment and tax revenues, and causing a substantial drag on Finland’s economic performance.

The ability of small economies to navigate this heightened risk profile will be more central to their performance than any general weakness in globalisation. Strategic foresight, the active management of specific risk exposures, and building national economic resilience are priorities in this environment. And there are also opportunities to be captured, as new growth sectors emerge.

Many small economies are beginning to reduce exposures to geopolitical risk; are working to return public debt to sustainable levels after the pandemic; and are building resilience into supply chains (Singapore, New Zealand, Ireland, the Nordics, and others). At the same time, investments are being made to capture opportunities in the low carbon economy as well as increased investment in research and innovation to strengthen competitive advantage (the Netherlands, Denmark, Singapore).

The agility and responsiveness commonly demonstrated by small advanced economies will be particularly valuable in a disruptively changing environment.

This small economy approach to managing emerging risk exposures is directly instructive for firms, which by definition have high levels of idiosyncratic risk exposure. Indeed, there has been substantial dispersion of performance across firms/sectors through the pandemic. And creative destruction rates of listed firms remain high.

Rapid adjustment is required to a new world of higher borrowing costs, geopolitical frictions, supply chain disruptions, and disruptive new technologies. Famous Silicon Valley start-up incubator Y Combinator sent a strongly-worded letter to their network last week advising them on the need for action to survive in this new environment.

Playbooks that have worked well over the past few decades of low interest rates, intense globalisation, and geopolitical stability, will likely work less well. And as I noted recently, exposures have been accumulated through the prolonged period of good times – some of these positions will need to be unwound, from high leverage to concentrated exposures to geopolitical rivals. New positions of competitive strength will also need to be built.

‘Success breeds complacency. Complacency breeds failure. Only the paranoid survive’, Andy Grove

Those governments and firms that respond most quickly to this environment will likely have an edge; a recent presentation from Sequoia Capital pointed to ‘the survival of the quickest’. A good measure of urgency and paranoia is needed. Continuing to run fair weather models when the seas have turned stormy is unwise.

Indeed, in sailing, it is not measured velocity that matters, but ‘velocity made good’; the speed at which you converge to the target destination, given the winds and tides. Countries and firms need to set their sails and course for the storms that are arriving - and to do so quickly. Opt for constructive paranoia rather than complacency.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

10 Comments

Thanks David. Just what we all need, more paranoia. Albeit constructive paranoia. We live in the age of paranoia as media bombard us with their version of the global realities on a daily if not hourly basis. One option might be to disconnect from the media altogether. However, just because most media are paranoia fear mongers, there is also a fraction of them that are actually helpful, if you know where to look.

Your posit today is spot on, but will also be torn apart by those not wanting to transition at all, especially into the great scary unknown. Your point though is poignant & should be a challenge to all of us in what is obviously a time of great change, in amongst an age of great change, so it is not the place for the faint of heart.

The ingredients to persevere & indeed profit from these moments will include vision (David's foresight) courage, commitment & co-operation, not components we currently display in abundance, sadly, especially in our shrinking democratic western cultures, which seem to be tearing one another apart if what I see & hear is anything to go by.

Sites like interest.co are a key communication tool for those interested in wanting to help get the next chapter right. If we can just bare with one another (relate) a little better in the hope of a future of possibilities & little less of the personalities, then we might just stand a chance.

So we are moving into what is likely to be a more turbulent period as we transition to a new economic and political regime. There will be rapid, at-scale changes on a broad range of fronts. The 1970s are a useful analogy for this transition; a rolling series of economic, political, and policy shocks that lasted for 10-15 years.

Agreed, but there are some big differences between the here and now and the 1970s, particularly private debt obligations in both the developed and the developing countries. Regarding the developed countries, a representative individual has had more acess to debt that in the developing countries.

You might want to re read your last sentence……

Cheers and corrected

This has been led by printing and distributing cheap money - have distorted the economy, only to watch, is the economy beyond repair before it dismantle completely.

A 'small advanced economy' is especially exposed - particularly one like NZ that exports replicable primary goods (timber, dairy) and imports energy and technology.

If either of our political parties thought beyond 3 years - they would be pitching a plan based on domestic energy security (transition from petrol / diesel, new hydro, trains, solar etc), food security (including reduced reliance on fertiliser - very sensitive to energy prices), and the development of increased technological capacity (selecting an area of focus that we can get out in front on). Selling these necessary changes as key to ensuring our economic and environmental futures will be a lot easier than trying to get boomers to accept change in the name of climate change alone.

We would also, of course, be re-thinking our relationships across the pacific - with a focus on how we bring together strategically our collective natural resources.

The youngest Boomer is 58. They are likely in a ‘save hard’ mode and therefore not the people who need to change their behaviours. I think the biggest problem is the Left of politics. Neither Labour nor the Greens seem to be able to honestly tell their voters that there must be pain, even if uneven, if Climate change, is to be slowed. The 25 cent fuel tax cut is a good example.

The 25c/lt cut is a bad example wrt climate change. This represented a reduction in the Govts windfall tax profiteering when fuel prices increased 50% earlier this year.

We might only just getting going on inflation, if diesel supply is crimped prior inflation will look trivial as food production and supply chains lock up.

I'm going to have to be a little critical of the interest.co.nz community here as well. Only last year when we closed the Marsden Point refinery many argued that New Zealand didn't need refining as a Strategic Capability.

We need some version/s of this

https://www.stuff.co.nz/environment/climate-news/300589778/how-a-shallo…

but narrower, deeper and with a cavern cover to minimise evaporation. It should also be owned by a State Energy Dept and used to regulate the spot market price of electricity to reduce the rent seeking behaviour of the current energy monopolies.

Coupled with subsidies for household solar systems and provision for the economic development of small scale geothermal projects without the burden of the bureaucratic process currently required. This would enable the first step of the electrification of our transport system by having enough affordable renewable electricity for all income groups to use.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.