By David Skilling*

As countries from Sweden and Denmark to the UK begin to lift remaining Covid restrictions, it is useful to look at the countries that have done ‘best’ in managing the Covid crisis – and why.

The caveat is that Covid will remain with us for some time so things may change. I have noted the winner’s curse: countries that do well in one phase of Covid have often under-performed subsequently. But after almost two years of the pandemic, some assessments can be made.

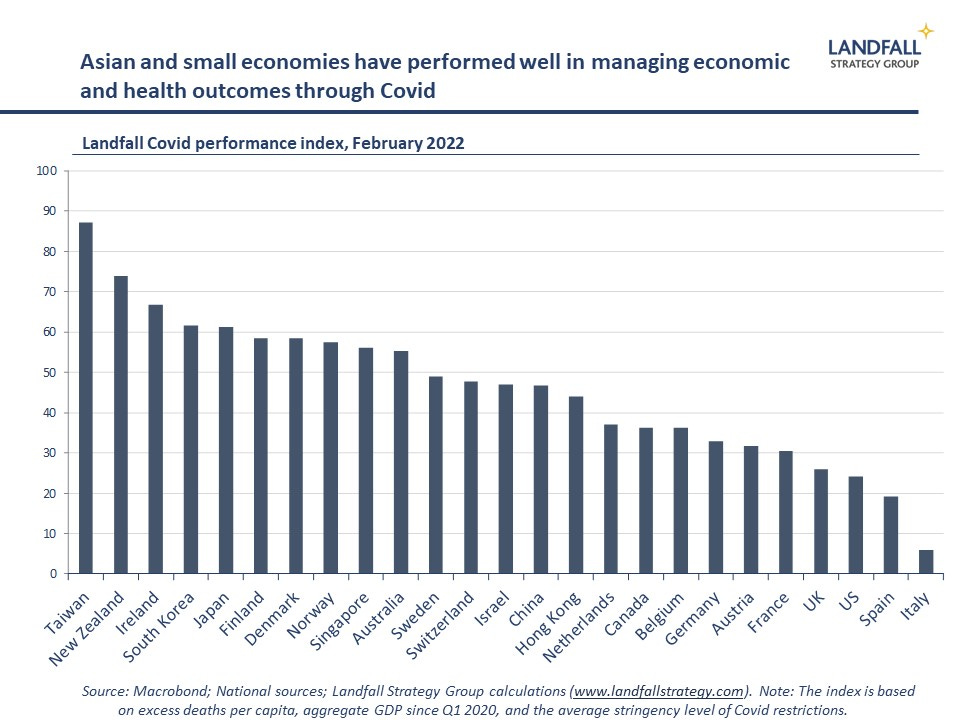

To put some structure on this, I construct a simple index of overall performance in managing Covid. This index includes measures of excess deaths per capita over the Covid period; strength in GDP performance since Q1 2020; and the average stringency of Covid restrictions.

There is some geographic variation, with many Asian economies – from Taiwan to Singapore and New Zealand – having done well in keeping Covid cases and deaths down, through tough approaches to containment, as well as generating strong economic outcomes. Looking forward, however, it will be challenging for some Asian countries to relax restrictions – from China and Hong Kong to New Zealand. Some of this strong Asian performance may weaken over the next year.

There is also a national scale dimension. The Nordics (note Sweden) and other small northern European countries (note Ireland) are also near the top of the rankings. At the other end are large countries like Spain, Italy, the UK, and the US. Overall, small countries have tended to do better – although with some variation (note Austria, Belgium).

Institutions matter

And there is an underlying institutional framing to performance. I have previously discussed the positive correlation between measures of political and social institutions and Covid approaches and outcomes across advanced economies. These characteristics have more explanatory power than pre-Covid measures of pandemic readiness, which ranked the US health system in first place – and countries like Singapore and New Zealand towards the bottom.

This institutional framing received further confirmation in a study published in The Lancet last week. This global study found that ‘Measures of trust in the government and interpersonal trust, as well as less government corruption, had larger, statistically significant associations with lower standardised infection rates’ (as well as with vaccination rates). ‘Getting to Denmark’ in terms of levels of trust would have reduced global infection rates very substantially.

Strong political and social institutions have made a valuable contribution to good Covid outcomes. And it is small advanced economies that perform well on these institutional and trust measures, going some way to explaining why they have managed relatively well through the Covid crisis.

Beyond Covid

Covid is not the only domain in which institutions shape performance. There are well-documented links between the strength of political and social institutions in generating strong, sustained economic performance (state capability, government accountability, absence of corruption, trust in institutions, social trust, and so on). Singapore is a canonical example of a country that has done this well, Argentina an example of a country that has not.

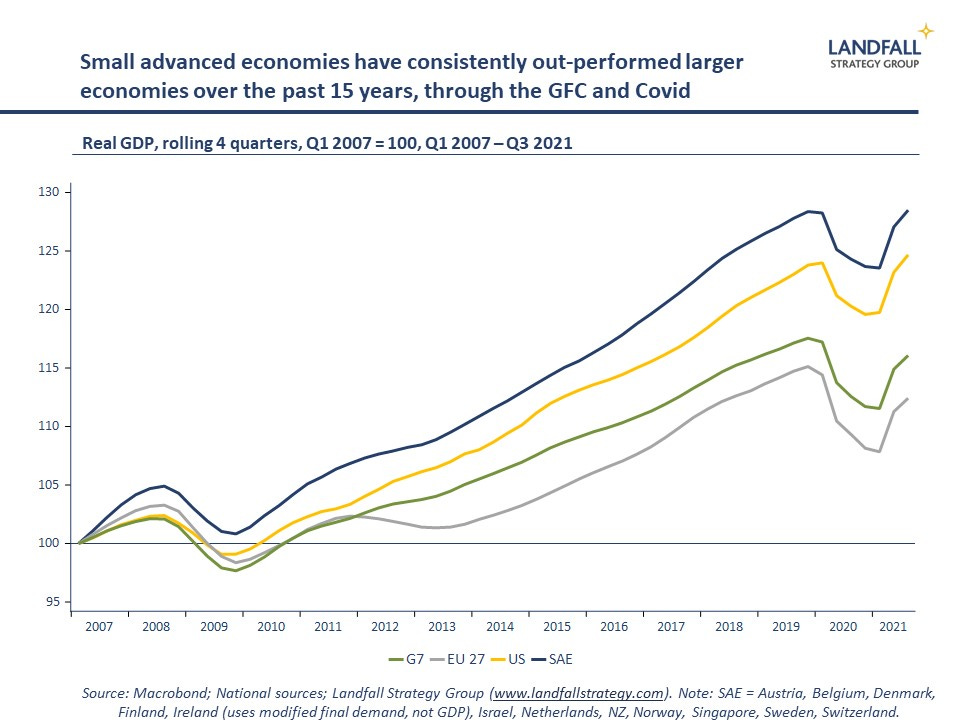

The strength of institutions and trust in small advanced economies will provide them with an increasingly strong competitive advantage. Although obituaries have been written for the small economy model given the challenging global environment, small economies continue to consistently out-perform larger economies. This resilient performance is importantly due to high quality policy choices and agility.

The small economy experience also shows that trust in institutions is not fully exogenous: it can be earned (or lost). Institutional trust is high in small economies because their political institutions have delivered good outcomes: GDP growth, employment, social mobility, and so on.

For example, many small advanced economies – which are deeply exposed to the global economy – have managed globalisation well. They have invested to capture the benefits of globalisation, while setting policy (social insurance, labour market policy) to manage the costs and risks. As a consequence, a political consensus remains in favour of openness.

In contrast, larger economies like the US and the UK have not managed these pressures well even as globalisation and technology have reached further inside their economies. The pressures on labour markets and income inequality have grown, leading to a political backlash on issues from trade to migration – as well as broader challenges to their political systems.

In what will be a deeply demanding global context ahead – from climate change to disruptive technologies and geopolitical rivalry – it is economies with strong institutional capabilities and high levels of trust that are likely to perform best. These systems can set high quality policies that respond to the new context, and are able to respond effectively to increasingly frequent periods of crisis and stress.

The strength of social and political institutions – the ‘intangible infrastructure’ of successful economies – is the single most important characteristic that I look to as a guide on future economic outcomes (as well as medium term market performance).

A democratic recession?

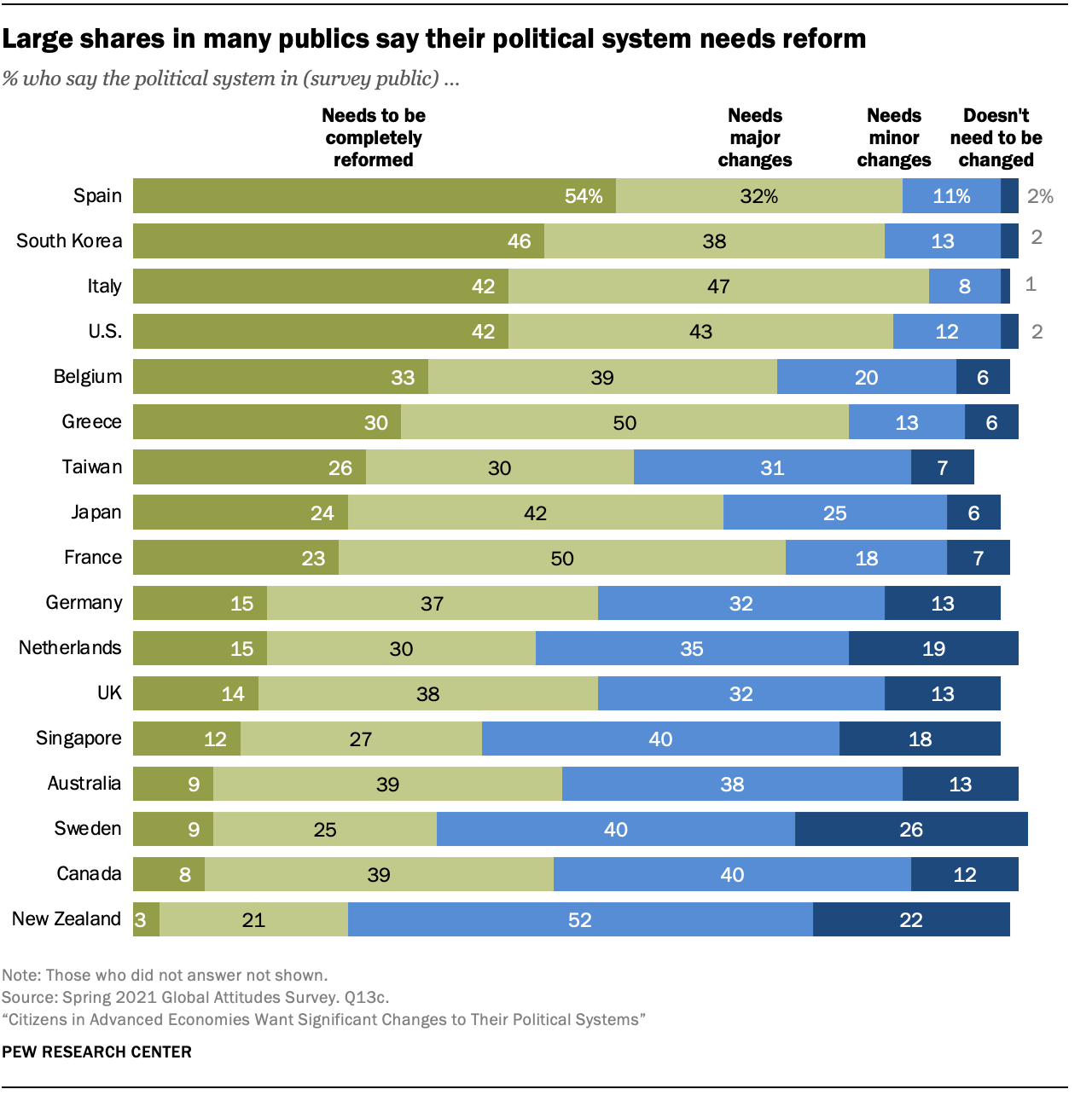

But the global outlook for this intangible infrastructure is concerning. A Pew survey in December found that substantial shares of populations in many democracies favoured substantial changes to political systems because the current arrangements were not delivering.

And the Economist’s annual Democracy Index, released this week, reported a further weakening in the health of democracy around the world. Again, small advanced economies dominate the rankings, taking the top seven places, led by the Nordics and New Zealand.

Similarly, measures of institutional trust have been declining around the world. Covid restrictions have taken their toll on social and institutional trust in many countries. And the redistributive effects of issues from inflation to new technologies and managing climate change will place further pressure on political systems over the coming period.

Those economies that can manage these pressures best, and maintain high levels of trust and institutional capability, will perform best in what will be a period of disruptive change ahead.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

12 Comments

I've paid my dues

Time after time

I've done my sentence

But committed no crime

And bad mistakes

I've made a few

I've had my share of sand

Kicked in my face

But I've come through

And we mean to go on and on and on and on

We are the champions, my friends

And we'll keep on fighting till the end

We are the champions

We are the champions

No time for losers

'Cause we are the champions of the World

-Queen

Interesting china isn't on the list neither is Russia.

Perhaps it’s because they’re not considered “advanced” economies?

I think the key word is democracy, but Russia would consider itself a democracy , China not so much but it would be interesting to see such a survey done in China to guage their feelings.

I’m not sure a survey in those countries would be valid. If you are in China or Russia and a guy comes to your door and asks if you like the political system, I’d suggest you say yes.

To put some structure on this, I construct a simple index of overall performance in managing Covid. This index includes measures of excess deaths per capita over the Covid period; strength in GDP performance since Q1 2020; and the average stringency of Covid restrictions.

A smaller country with a smaller population will always do well in an emergency if the basic institution is sound- as long as the public service isn't third world disarray or having a civil war.

Being in the top three in your index sounds fantastic. But you should have elaborated on the problematic use of GDP as a component of your index structure.

Since,

GDP = Private consumption + Government spending + Investment on capital, inventories and housing + Net exports

A mass printing of money, uplift in social benefits payouts, increasing government hiring and dairy prices has boosted our GDP numbers into a unsustainable and unrealistic levels in the context of a pandemic.

Just to give some context on just the money (M1) printing spree since March 2020,

Taiwan: +33%

New Zealand: +75%

Ireland: +40%.

And that's not even having to look at the bloating rise in government hiring, supply chain caused dairy price surge and additional and incremental beneficiary payouts.

Therefore I think a better index would be one that incorporates hospitalisation, wages and social mobility while leaving out GDP.

The thing is that NZ “saved” for this rainy day while other countries pushed their govt debt to the extreme (by saved I mean didn’t borrow as excessively). Our public debt is still low by international standards. Probably another advantage of a small country, we don’t just vote for excessive spending or excessive tax cuts, we try to find somewhere in the middle that works.

I'm surprised there are so few comments on this article. It's good to see we are still shoulder to shoulder with the Nordic countries.

Good news for the Labour government and Ardern I guess.

I wish they could ease up a bit on the mandates now many are vaccinated and let freedom reign. We are never going to get through to the protestors. At least the protestors show that we are not all sheep. Most Kiwis should be more worried if there was no protest.

If we are never going to get through to the protestors, why ease up a bit on mandates that serve a public health function.

The freedom many of the protestors are seeking is the freedom from the consequences of their own (fact free) decisions.

Mr Skilling has selected his measuring sticks very carefully. There are many measures of global societies. I remember reading the RBA graphs last year of which there were 143 from memory, & that was only what they could measure. Imagine what they couldn't measure - the list would be endless. I understand Mr Skilling's maximum wordage for an interest.co.nz article, which is where the links come into it, and yes, we are are all selective to a point, however, I would add a pinch of salt to the article before rushing off & emailing the govt your Well Done coms just yet.

As he points out, it's not over rover.

NZ seems to have been used to test out more radical changes against the Will/vote of the people to provide a sample test for the world.

Eg Rogernomics in the 80s - radical removal of subsidies, floating exchange and sell off of govt assets. Adoption of technology as NZ can quickly implement across the entire country Eg early eftpos. Zero COVID & closed borders - have we been doing these purely for our own ‘benefit’ or is NZ the guinea pig?

Inflation is the tail wind from the economic and financial measures taken during Covids.

Time will tell how NZ fares against other countries with that.

He didn't take inequality and housing into his measures. This would bump NZ down a bit

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.