By David Skilling*

Just over two years ago, I relocated from one end of Eurasia (Singapore) to the other (the Netherlands). One reason for this move – after 11 fantastic years watching Asia and the world from Singapore – was to get a different perspective on global economic and political developments.

And despite spending much of this period in varying forms of Covid lockdown, being in Europe has provided a good view on changing global economic and political dynamics.

Although the centre of global economic gravity has been shifting inexorably towards Asia, and US/China is the single most important bilateral relationship, Europe sits on emerging fault lines in the global system. Dynamics at one end of Eurasia have clear echoes at the other. There are two reasons for Europe’s exposures.

Europe’s exposures

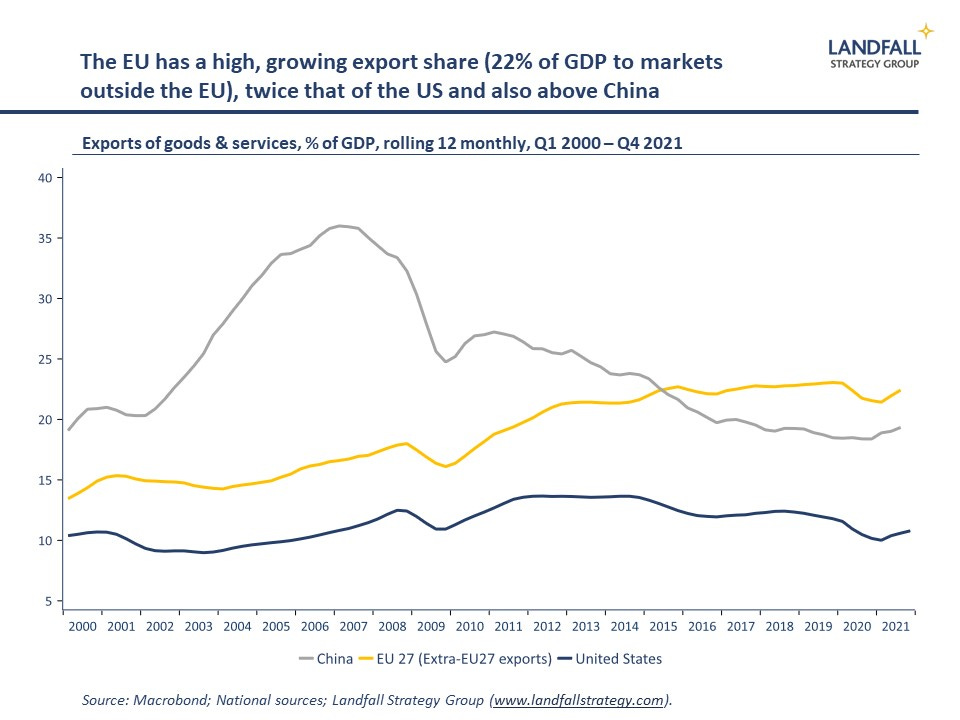

First, Europe is a highly open economy – with substantial exports and imports (outside of the EU27) as well as investment flows. As a share of GDP, these international flows are significantly higher than in the (similarly-sized) US as well as Japan and China.

This international presence is a source of economic dynamism. But in the context of geopolitical tensions increasingly playing out through economic channels, this is also a source of exposure. Indeed, the growing economic tensions with China are evident in Europe.

For example, China has recently sanctioned Lithuania after it strengthened relations with Taiwan (now the subject of a WTO complaint by the EU). And other countries, from Sweden to Norway have been on the receiving end of Chinese pressure. The potential for economic costs from bilateral political tensions is felt acutely in Europe because the EU/China trade relationship is the largest in the world.

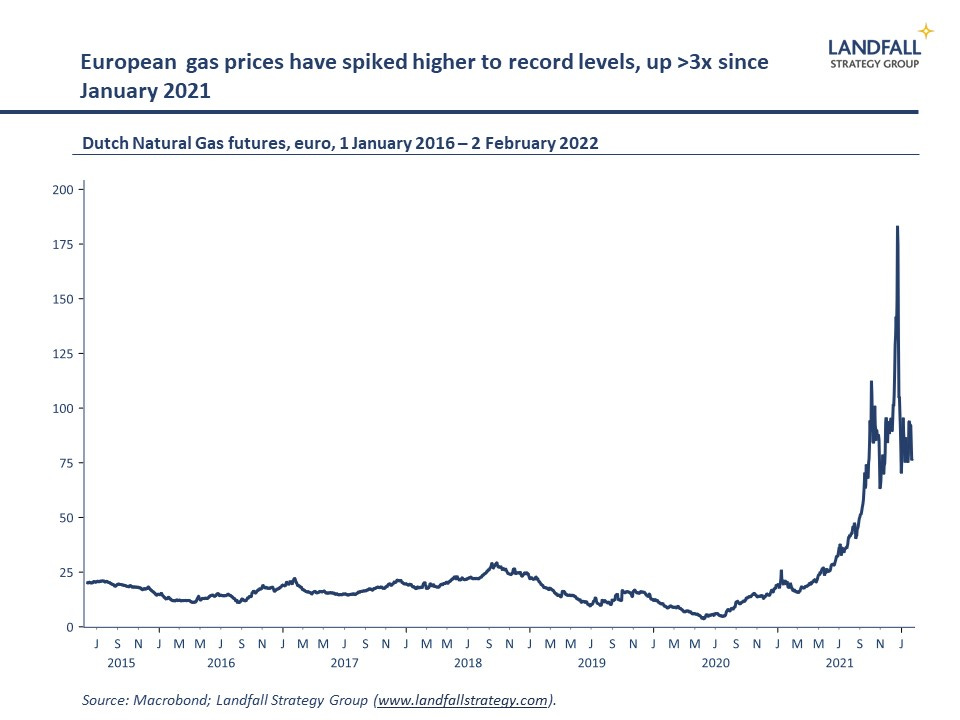

And Russia has been using economic leverage to impose pressure on Europe; restricted gas flows have led to record-high gas prices over the past several months in Europe. The IEA head recently said that Russia could increase gas deliveries to Europe by at least one-third, and linked tight supplies to geopolitical tensions.

The second reason is geography: Europe neighbours Russia, a country that is looking to reshape the regional political and security space (and beyond). This is most obviously seen in Russia’s current actions on the border of Ukraine (as well as its 2014 invasion). Even neutral Ireland, on Europe’s west flank, has found itself under unwelcome Russian pressure over the past week or so.

Although I think it unlikely, the risk of direct military conflict in Europe is as high as it has been for some time. But at a minimum, Russia is applying economic and political pressure, looking to exploit differences in Europe, and build a de facto sphere of influence across its neighbours. This has clear parallels with China’s behaviour in the South China Sea, as well as its threats to Taiwan and its actions in Hong Kong.

So Europe is currently ground zero for the weaponisation of international commerce as well as for pressures on the global political and security system. The way in which Europe responds will shape the way in which the global system evolves: from the fragmentation of the global economy to China’s perceived space to act on Taiwan.

Responding to a changed world

After an initial period of hopefulness/naivete, many European countries are becoming more hard-headed on these realities and are pushing back on Chinese economic and diplomatic aggression. Similarly, there is broad agreement on imposing economic and political sanctions on Russia if it escalates further in Ukraine.

This changed settings are not the default preference of Europe, but global realities have caught up with it.

‘You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you’ (Leon Trotsky)

In economics, there is an increased focus on strengthening economic resilience (‘strategic autonomy’) at national and EU levels – from energy markets to technology.

The EU’s Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with China is on hold after sweeping Chinese sanctions on European institutions; the EU is preparing new supply chain legislation, focused on human rights violations, which will likely catch China-exposed firms; and investment restrictions are being more widely imposed on Chinese firms. This is not yet decoupling, but there is a much more deliberate management of exposures.

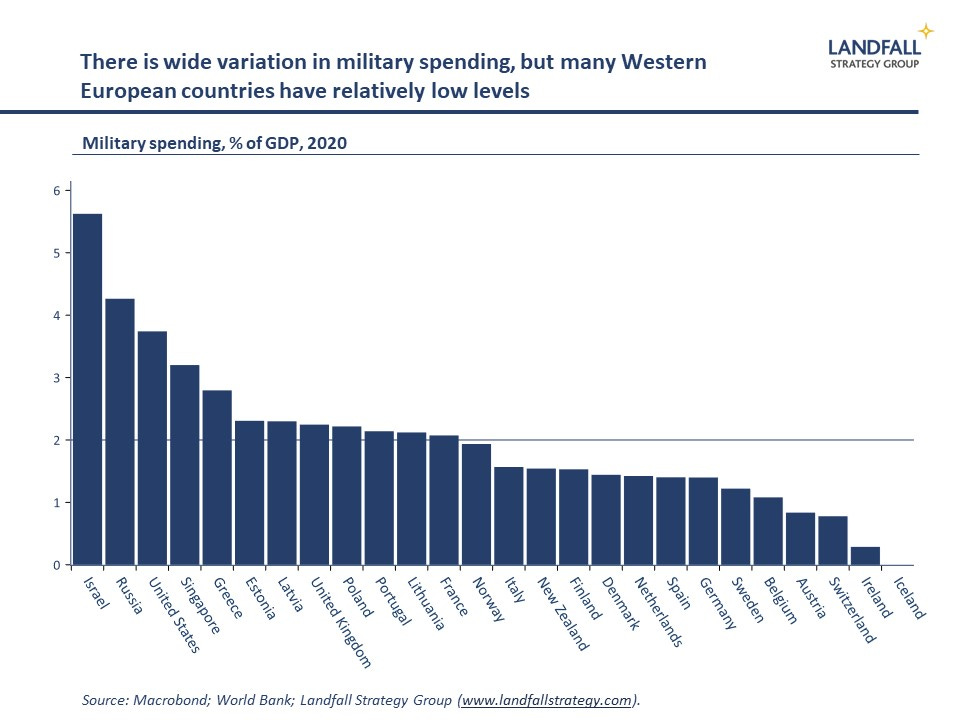

In terms of the security response, many European countries have committed forces or equipment to Ukraine and neighbouring countries. Across Europe, countries are looking to strengthen and update their military and strategic capabilities: several have developed Indo-Pacific strategies, for example. The political and public consensus on these issues is shifting.

However, there is significant variation across European countries in the strength of their responses to the economic and political dynamics. The Ukraine situation has illuminated some of these differences. The Netherlands and the UK, as well as several central and eastern European economies, have been punchier in their response to the Ukraine tensions than Germany (note also Germany’s support of Nord Stream 2)

Similar, large countries with big economic exposures, such as Germany and Italy, have less inclined to take tough stances on China. Smaller economies, with big exposures but acute sensitivity to big power politics, have often been quicker to act.

These differences across countries make it very difficult to establish a common EU approach to geopolitical issues (although the current tensions have made NATO more attractive to non-members such as Sweden and Finland). Indeed, the US has been central to mobilising action on Ukraine.

The implication is that much of the economic and security response will take place at national level and in coalitions of the willing - where interests and values align and consensus can be formed - rather than at EU level.

Europe as a swing state

Overall, Europe should be watched carefully for its response to emerging economic and political pressures. The geography and relatively closed economy of the US has made it easier for it to adopt hawkish approaches on China and Russia than for Europe. But as a highly open economy, European actions are a good barometer for the state of the global economic and political system.

If Europe responds to current economic and political pressures in a more assertive manner, this will powerfully shape the global system: signalling greater fragmentation of the global economy, a greater focus on resilience, and increased investment in hard power. This may not be Europe’s preference as an outwardly-focused economy, but it seems the likely direction of travel given current realities across Eurasia.

Even for countries on the other side of the world, decisions that are taken in Europe will have deep consequences.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

17 Comments

"European actions are a good barometer for the state of the global economic and political system."

Um, more of an example of what not to do for other jurisdictions:

- Switch off dispatchable power sources without building out nearly enough unreliables or plan for any transition, really.

- Poke the bear without having any substantive military capability.

- Fail to bring forth enough children to sustain population and cultures.

- Require immigration from vastly different cultures without requiring assimilation.

Then gape in wonderment as things fall apart....

At the close of WW2 Russia & China were part of the Allies, opposing the then Axis, Germany, Italy, Japan & some east Europe ring ins. Very shortly thereafter, something of a complete role reversal wasn’t there. Whether under Russian Tsars or Chinese Emperors these vast nations have existed as totalitarian regimes since before recorded time. For a while, Genghis Khan actually managed a merger of large parts of middle ground. The new, 20th century, regimes are totalitarian too. Thus it is hardly surprising that the populations are completely expectant of this type of rule, their history has imbued it into them, deeply. Those born in China in 1949 are now in their seventies, indoctrinated to the CCP’s ideology, there can only be a few left, as a percentage, who knew anything different as an adult. Seems to be that the Western powers have continually failed to realise that their own “democratic” way of “fair play” is actually quite alien, not at all easily understood & accepted by the people of these very different nations. Churchill’s enigma in a puzzle quote still resonates.

The West has become soft and divided, Putin knows it. If Russia decide to invade Ukraine I doubt NATO will do much about it. You never know Putin might decide to keep going and reclaim all former Soviet states and maybe more as I doubt there will be much hard opposition. USA won't want to be the first to use nukes and they will probably pack up and head home to their own civil conflicts.

US President Joe Biden announced on Monday that he was designating Qatar, the Gulf state, as a “major non-NATO ally,” stating that the sheikdom was a “good friend and a reliable partner.” The move comes amid efforts to present Doha as an alternative to Russia for European exports of Liquid Natural Gas (LNG), in an effort to isolate Moscow. Link

I think the fact is Europe is in a catch 22 situation. Their only way out is probably nuclear to be self sufficient. Hopefully sense prevails and common prosperity is the out come.

If war breaks out in Europe we will be ever more dependent on Asia, particularly China

So true Foxglove. I believe that 4 out of 5 people on planet Earth today, live in authoritarian regimes. I believe it because I was lucky(?) enough to see it for myself. Outside of North America & Western Europe & a little bit of the South Pacific, most countries are run ruthlessly (usually involving guns) & almost no one in the West really understands this. Some do. Some get off the beaten track & venture out into the big bad world which I can assure you, is no picnic. Even in places where you feel relatively safe, you still get sick.

We may bag NZ but we can still pull up at a red light & be reasonably assured that nobody with a gun will jump in beside you, force you to drive somewhere remote, kill you & then rob you... & have a good chance of getting away with it. That time may come, but thank God it's not here just yet.

It’s interesting, about twenty years ago talking to a taxi driver in Chicago, a Russian who had been there for ten years or so and was heading back. There is a strong man there now and everybody knows where they can stand. If I did some of the things that I have done here, I would still be in jail at home in Russia, but I’m still going back.

must say the whole west is just a gutless paper tiger.

the US only dares to bomb countries way smaller.

A bit like china then .

Arent you lucky that China has almost the smallest in the world then.

Isn't the world better when countries are peaceful tabby cats then when they are rapacious, wild tigers.

Although I think it unlikely, the risk of direct military conflict in Europe is as high as it has been for some time.

Deliberate false flag? - Bloomberg accidentally reports that Russia invaded Ukraine

Xing,

You are becoming increasingly shrill and unpleasant. In fact, just like your 'President for life'. I had thought that was the sole province of banana republics.

May be just a coincidence.

Putin's Russia went into a fight with Georgia when Beijing held the Summer Olympics in 2008. The fight erupted on the opening night.

Even if Putin does invade Ukraine how does he get to an end game.

- Put in a puppet government with a population that is largely against said government

- Keep an occupation force in Ukraine (that will be several hundred thousand troops - with the risk of of casualties - another Afghanistan) .

- ?

Even if an agreement is signed saying Ukraine will not join NATO there is no guarantee that in ten years time that agreement is ripped up.

Ukrainians are not Russians.

Russia invading Ukraine would be a tactical move but not a strategic one. Putin has no way of controlling the end game. Additionally he has already said he has no intentions of invading Ukraine

It's not as if Russia hasn't done this sort of thing before - the Winter War , annexation of the Baltic states.

The Winter War primarily concerned Finland which was then more a Nordic rather than Balkan State. The Soviets moved on Finland because they could not get an agreement to establish a demilitarised zone, that would take Leningrad out of artillery range. The Soviets did not have any easy time at all, but sheer numbers & weight of armour prevailed after about three months. In essence though you are dead right, that incursion is a precedent in itself in character and intent as to where Russia is positioning itself with the Ukraine. Interestingly, the other three, Latvia,Lithuania, Estonia had been ceded to Russia by Sweden in the 18th century. They became independent after WW1 but led by Estonia had to fight off the Bolsheviks to remain that way. WW2 saw them swamped by the Nazis one way and then the Soviets back the other way. . So then, if Mr Putin believes Russia has historical ownership of the Ukraine, the Baltics are obviously similarly grouped into that ambition. With the added incentive of warm water North Sea ports.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.