By Siah Hwee Ang*

Of the free trade agreements currently under re(negotiation), many are hanging in the balance.

The NAFTA, UK’s FTA with the post-Brexit EU, and the US-South Korean trade agreement are among these. Not to mention the TPP, with uncertainty around the progress of the agreement beleaguering its remaining 11 members.

For many countries, a slowdown is expected.

China is the largest trading nation in the world. Given the size of its economy, a Chinese slowdown has serious repercussions for the global economy.

While China is still working on more FTAs, its trade with non-FTA countries continues to grow.

Initiating the One Belt One Road (OBOR) (and hopefully getting many other countries involved) is viewed as a solution to China’s economic decline.

The potential rise of other economies through the OBOR will help to sustain global economic growth given China’s inevitable slowdown and the uncertainty around the US and EU economic regimes.

Four years in, the OBOR has certainty picked up speed in some countries and regions.

It is clear that OBOR is not about trade per se—it enables trade.

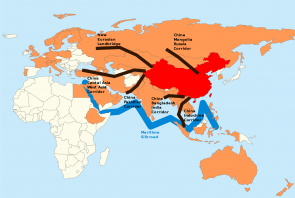

OBOR covers a wide range of activities, as covered in recent articles around what’s happening on The Belt and The Road.

OBOR’s focuses are on infrastructural development to enhance policy coordination, facilities’ connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds.

Yet many of these aspects are hard to measure and assess based on a cost-benefit analysis.

In a way, it poses a similar situation to the debate around extending (or not extending) the Wellington Airport runway, i.e. if we extend the runway will people come?

In other words, it’s a major challenge for New Zealand’s mindsets.

We should expect a lot more discussions around when and how we can observe ‘outcomes’ from OBOR activities.

An exercise like this would mean teasing out what can be directly attributed to OBOR and what happens as a natural course of development.

The powerhouses of the US, Japan and India have yet to come to play in OBOR.

This may reflect their growing concern around China’s role in the global economy and the leadership role that emanates from OBOR.

Countries keen to strengthen their relationships with China and re(negotiate) FTAs with the country will definitely have to engage with OBOR.

Again, for the US, Japan and India stakes aren’t that high yet.

Despite the scepticism, the constant message coming out of Beijing is that “Though originating in China, the Belt and Road Initiative belongs to the whole world”.

Meanwhile the OBOR continues to do wonders for economies such as Pakistan, Kazakhstan and Myanmar, with others likely to follow suit. Observations within these countries are showing that the OBOR does create local employment and contributes to the local economy in different ways.

After all, emerging economies still make up the majority of the global economy.

(This article is the final article of a four-part series on China’s One Belt One Road Initiative). The first three can be accessed here.

*Professor Siah Hwee Ang is the BNZ chair in business in Asia and also chairs the enabling our Asia-Pacific trading nation distinctiveness theme at Victoria University. He writes a regular column here focused on understanding the challenges and opportunities for New Zealand in our trade with Asia. You can contact him here.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.