It is very hard to make an argument to save via fixed-interest instruments.

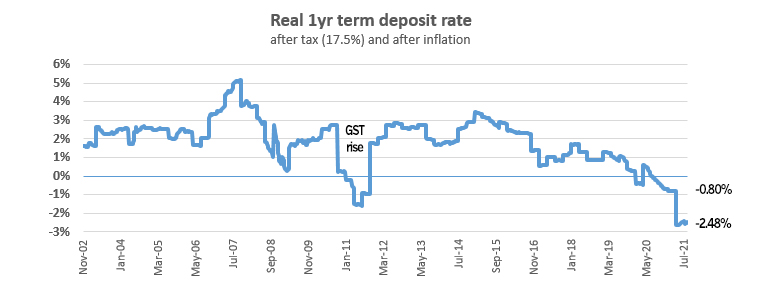

It is not news that interest rates on savings products are very low. They have been low for some time, and on an after-tax, after-inflation basis, they have been negative for almost five years now.

It is easy to 'blame' the money printing used to battle the COVID pandemic, but that crisis only started in March last year. The problem of negative returns for fixed-interest savers pre-dates that by about three years. So there is more going on here than what the Reserve Bank (RBNZ) has done recently.

And it is a global issue. It is a terrible time for savers and it is unlikely to get much better anytime soon.

One core reason is demographic.

A Bank of England official recently said: "We are only about two-thirds of the way through a multi decade demographic transition that is affecting interest rates. The key mechanism is not that older people have lower savings rates, but rather that, as people age, they hold higher levels of assets, in particular safe assets,” then they spend those savings down slowly when they hit retirement years.

That helps explain why interest rates have been persistently low across major economies - in Europe, the United States and Japan in particular - for years, even at times when those economies have been performing relatively well.

It won't be until this crop of boomers pass through over the next 20 years that a rebalancing of this effect will start to appear again.

In the meantime, the drive for 'safety' is pushing huge volumes of retirement money into very low yielding assets.

And those low yields are affecting other investor behaviours. The most obvious one is to drive up asset prices.

It also encourages wild risky behaviours, like 'investing' in cryptos, like chasing social media meme stocks on a herd basis. The greater fool theory is having its day in the sun as unsophisticated 'investors' merge the concepts of 'investing' and 'gambling'.

There also seem little doubt that the pandemic quantitative easing (QE) has added to the frenzy of low yields. Fortunately the unwinding of QE can be done deliberately when the immediate crisis passes.

But that won't necessarily mean interest rates will rise back above inflation on a tax-paid basis, because the over-arching demographic impulse is still there.

In New Zealand, savers took another body blow when the June quarter Consumers Price Index (CPI) was revealed at 3.3%. After-tax, after-inflation returns tumbled -1.68% pa just on that. CPI inflation jumped from 1.5% in March which caught policy-makers by surprise. The RBNZ had seen it rising to 2.6% in June and then falling away. Few other economists saw 3.3% coming either. And that throws doubt on the RBNZ Monetary Policy Statement forecast of +2.5% in the September quarter. This current bout of inflation might be 'transitory' but it will be at higher levels during that transition than policy makers had assumed. Or it might not be transitory, embedded into a new future in ways not assumed.

Like what you read? Support our journalists. Find out how.

Large economy ageing populations will keep savings high, spending-without-production elevated, and a fascination with get-rich-quick investments, for a long time yet, all of which will work to elevate inflation and depress yields for longer. Elevated inflation will work as financial repression, and to bring the global financial system back into some semblance of balance, that repression may need to be in place for decades to come.

This future won't be pretty for general savers. They are usually the "have-a-little-and-want-more" types but face a real risk of becoming have-nots. Some sort of circuit-breaker may well be needed to retain social cohesion, because the inability of the young to participate in the explosion in asset values will likely cause rising distress and anger. And it is hard to see an effective redress that meets the basic needs of the newly-angry without asset-value taxes. Anything else would work too slowly.

Savers should expect that on the current basis, negative after-tax, after-inflation returns on their savings will continue for at least twice as long as the five years they have suffered so far, and maybe very much longer. And if asset taxes do arrive, that will be another risk.

28 Comments

......and over the horizon flys the black swan.

Don't worry, you won't hear about it until it arrives.

The mantra doesn't include swans.

Global interest rates, well at least the ones that matter

https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/interest-rate.

If New Zealand wants to stay in the club the OCR is more likely to go negative than 150bps higher.

> It is very hard to make an argument to save via fixed-interest instruments

Not if you actually price risk into the equation.

There is a ton of government debt out there now with negative yields, which means plenty of people prepared to pay for a safe place to put their money. At this stage in the game it may make more sense to focus on return *of* capital, rather than return *on* capital.

Yields on govt bonds don't indicate anything other than central banks appetite for crushing interest rates, RBNZ now owns 60%+ of all NZGBs on issue and will gobble up more if they have to keep yields down. It has nothing to do with people looking for a safe place for their money and everything to do with manipulating interest rates.

LSAP has ended, but at peak the RBNZ held $53bn of government bonds, with the remainder (and the vast majority) presumably held by institutional and private investors at what are effectively negative yields.

Exactly right, very happy just to be treading water and keeping my savings head above water. Almost impossible to tell how this mess is going to finally turn out and I'm happy just hanging on to what I have, forget about gains.

Bitcoin enters stage right. Few...

All advanced economies suffer the same fate.

The most admired welfare countries in Scandinavia are all now running on negative interest rates. When a country transit from manufacturing to services, the first phase is always exponential prosperity followed by a great decline.

It also encourages wild risky behaviours,

So why is central bank policy resulting in people having to participate in "risky behavior"? What kind of guardianship (that they speak of) is that?

Growth = interest

No Growth, no interest.

The real issue is that unhealthy proportion of savings is now channeled into the housing market rather than into productive investments. Permanent financial repression, i.e. artificial low interest rates, is not going to fix this - on the contrary.

The "have-a-little-and-want-more" types David mentions, currently own a significant part of NZ's $270 bio savings and term deposits. Imagine if these humble savers get fed-up with permanent low returns and buy more properties or expose themselves to risky investments.

To fix financial imbalances we need an active Government and a banking sector that are prepared to invest in NZ's future, for example investments that address the climate crisis, NZ's low productivity and poor infrastructure. Savers will be more than happy to contribute if they get acceptable returns.

A low interest rate policy is a dead-end street: the RBNZ must end this Orror show!

Exactly right. These reckless ultra-low interest rates do not stimulate the real economy - they only create asset bubbles that ultimately depress the purchasing power of the new generations, and they are highly destructive to the longer term balance and health of the real NZ economy and entire financial system. They are just a highly distortionary, ultimately counter-productive sugar rash, whose cost will have to be paid in many ways.

And the crazy expensive housing market is a large part of why birth rates are falling, which leads to further ageing of the population...

Thats one way to reduce population induced climate change.

In recent decades, the structural growth rate of US GDP has slowed considerably, to about 1.6% today – about 2% lower than the post-war average.

If there has been anything more unusual about the past few quarters, the love of safe and liquid assets hasn’t been that thing. Instead, it has been the turning away from loans and lending – there the data aligns with Mr. Dimon if, however, for the opposite reasoning.

Loans had already been largely avoided in the post-2008 era, but since 2011 had at least been advancing in nominal and absolute terms (though in linear terms, still shrinking).

Apart from the big jump in loans in Q2 2020 as companies all over the place forced banks to standby their existing revolvers, lending has only dropped ever since. No matter the Fed and its variety of puppet show variations, nor Uncle Sam’s overtures into increasingly every corner of the economic sphere. Banks are saying “yes” to safety in a big way and “no” to risk-taking in a bigger way (which is what loans are, especially in the sense of liquidity risks).

In fact, the banking system’s asset side has been driven exclusively by the most liquid assets: UST’s and agencies but also the Federal Reserve’s bank reserves. Each of those has increased while risk-taking types of assets are now explicitly shrinking.

If we remove bank reserves, UST’s, and agencies, you can see all-too-clearly why there hasn’t been any inflation in the post-crisis era – and equally why there isn’t likely to be anytime soon. The banking system – now through Q1 2021 – continues to de-risk the collective balance sheet. Link

This is what Milton Friedman called the interest rate fallacy, and it indeed refuses to die. We can tell what monetary conditions are in the real economy, as opposed to financial liquidity, though the two can be linked, by the general level of interest rates. When money is plentiful, interest rates will be high not low; and when money is restricted, interest rates will be low not high. The reason is as Wicksell described more than a century ago:

[The natural rate] is never high or low in itself, but only in relation to the profit which people can make with the money in their hands, and this, of course, varies. In good times, when trade is brisk, the rate of profit is high, and, what is of great consequence, is generally expected to remain high; in periods of depression it is low, and expected to remain low.

When nominal profits are expected to be robust, holders of money must be compensated for lending it out by higher interest rates. Thus, the same holds for inflationary circumstances, where nominal profits follow the rate of consumer prices. During the Great Inflation, interest rates weren’t low at all, they were through the roof well into double digits and higher by 1980. At the opposite end in the Great Depression, interest rates were low and stayed there because, as Wicksell wrote, the rate of profit was low and was expected to be low well into the future. High quality borrowers were given as much money as they could want while the rest of the economy was deprived of funds; liquidity and safety being the only preferences in what sounds entirely familiar. Link

Double whammy. Low rates from the Bank and higher inflation on the street.

Time to give tax rebate for interest earned from Bank deposits.

First 10k, no tax. Come on Grant Robertson. Make it happen.

Yes no one is interested in TDs under 2.5% less tax.

I know many over the age of 60 owning houses they would prefer to sell, but are not interested in TDs that are a losing investment after inflation and tax.

The government needs to provide an incentive to these oldies to sell the houses they dont really want.

Why not match the tax on housing gains, what is it now, oh yeah its ZERO thanks to Winston.

Otherwise these houses will be sat on and not released to the FHBs.

TOP fixes this. Asset test. Done.

Missed the bus now but the third generation Mazda RX7 would have been good investments. I'm wondering what else may increase markedly in value. Toyota MRS? Probably not high performance enough but good RX7s are fetching six figures now. Was a handsome car.

As teenagers my brother and I had RX3s. Mum and Dad ended up with an RX5 for a while.

Fabulous cars. I had to make do with a Viva HB. Must have liked it because I later bought a Vauxhall Chevette. Actually really liked the design of that car and I imagine an immaculate example would be worth something however the performance versions of all seventies and eighties cars are likely very collectable. The Chevette HSR for example.

I had a blue 1981 Mazda Rx-7 in original condition for many years. One of the prettiest cars ever made. I sold it for $3k in 2000. They're selling them for $50k+ now :(

https://www.trademe.co.nz/a/motors/cars/mazda/rx7/listing/3159625841?bo…

The Toyota MRS is a turd. The MR2 GT will be better long term prospect. Owners now trying to get $25k but that doesn't mean they are selling.

The new 60/40 portfolio: 60% equities, 40% Crypto. As surmised by Cathy Woods.

That is a very brave call: 40% Crypto. You love to live dangerously, I guess. Certainty, such a mix will give your portfolio a good level of excitement.

I don't have 40% crypto, I have only 1.56% crypto, I was just saying Cathie Wood of AARK has surmised that's what the future portfolio will look like, and with NZ bond funds on negative returns since April (and probably for next decade) I'm not saying she's wrong, so long as US politicians don't kill crypto in the Infrastructure Bill.

I dont have 40%, I have much closer to 50%.

Cash is trash, get it into assets as fast as possible.

Lon term thinking, short term dips are for buying more.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.