By Bernard Hickey

The Basel-based Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has forecast that the ageing of populations in developed economies could act as a significant drag on real house prices and other asset prices over the next 40 years as an ageing population sells assets built up in previous years to live on the proceeds.

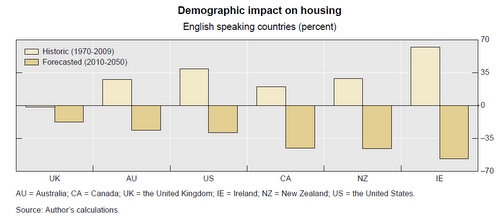

The BIS, which acts as a type of central bank for central banks, forecast that real house prices in New Zealand could be almost halved by 2050 because of the effects of an ageing population, while real prices could fall 35% in Australia and more than 50% in Ireland.

BIS economist Elod Takats made the forecasts for 22 developed countries in a paper titled 'Ageing and Asset prices'. It is also available in full here.

"Individuals borrow when young, and in their middle ages they repay these debts and also save for old age," Takats said in the paper, which included freshly compiled statistics showing how real house prices had changed over the last 40 years.

Takats found that the demographics of younger populations had helped boost house prices and asset prices in the last 10-20 years, but that this tailwind was now turning into a headwind for asset prices.

"The young save for old age by buying assets, while the old sell assets to finance retirement. This asset transfer can happen directly or through institutions such as pension funds. In this setting, the change in the relative size of asset buyers (the young) and sellers (the old), have consequences for asset prices," Takats said.

"In particular, the asset purchases of a large working age generation, such as the baby boomers in the United States, drives asset prices up. Conversely, if the economy is ageing, ie the subsequent young generation is relatively smaller, then asset prices decline. In the last 30 years, during the active years of the baby boomer generation, asset prices have increased massively," he said.

"Asset prices propelled by the boomers’ savings will be under pressure when this large generation retires and starts to sell its assets to the relatively smaller subsequent generation."

Takats statistics show that real house prices almost doubled in New Zealand in the last decade, making them the fastest growing in the developed world between 2000 and 2007. Australia's surge over 2008 and 2009 took it into the lead after 2007.

"The estimates suggest that real house prices will face substantial headwinds over the next forty years due to ageing. Though the results do not imply absolute real price declines, they suggest that in the next forty years house prices in advanced economies will face a more difficult environment than in the past forty years," he said.

Here is the chart showing the forecasts for how big the demographic headwind for house prices will be in 2010-2050 (dark bars), while the estimated demographic tailwind from 1970 to 2010 is shown in the lighter coloured bars.

Takats said the tailwind or headwind forecast did not necessarily result in real price falls or rises, given other factors could drive prices.

"The United Kingdom experienced one of the highest price gains in spite of the tiny negative demographic contribution. Italy and Korea enjoyed strong house price growth in spite of substantial demographic headwinds. This illustrates the strong role of other, non-demographic factors. In particular, the graph shows that demographic headwinds do not necessarily translate into real house price declines," he said.

Here are the real price results for all 22 countries in the dark bars with the demographic effect in the light bars.

New Zealand had a small tailwind over 1970 to 2010, but its real price rise was much stronger.

Headwinds and Tailwinds

Takats said two trends could either soften the headwind of the ageing population or make it worse.

Baby boomers may choose to work longer rather than retire, which would soften the blow. Pensions could also be cut, which would intensify the headwind as pensioners sell their assets more aggressively to pay for their retirement and healthcare.

"First, advances in technology and health are likely extend working age and redefine old age in the future. Though the analysis treats everybody over 65 years as old, working age could be extended in the future, as workers remain healthy longer and physically demanding jobs are replaced by more knowledge intensive jobs." Takats said.

"First, advances in technology and health are likely extend working age and redefine old age in the future. Though the analysis treats everybody over 65 years as old, working age could be extended in the future, as workers remain healthy longer and physically demanding jobs are replaced by more knowledge intensive jobs." Takats said.

"Second, old age entitlement, such as pensions and health care benefits, are likely to be cut in most advanced economies. Private corporations, facing intense competitive pressures, have already phased out of defined benefit pension plans – and replaced them with much less generous defined contribution systems," he said.

"In the government sector ageing related entitlement spending is currently set on an unsustainable path. Hence, lowering old age government benefits seems to be inevitable," he said.

"Consequently, the next old generation might have to run down their assets in old age more aggressively than previous old generations as their private and public entitlements would be much less generous. This would exacerbate the negative impact of ageing on asset prices."

Takats said the estimated ageing impact was relatively mild in the United States with around 80 basis points per annum headwinds. The drag was estimated to be much larger in most of continental Europe and in Japan.

"This finding is at the high end of earlier empirical estimates, but does not constitute an asset price meltdown. It is important to reiterate that the findings do not imply absolute real house price declines, as real house prices are affected by many other factors which could well compensate for the demographic headwinds."

Takat said one implication of the impact of ageing on asset prices was that public and private pension systems would struggle to meet their promises.

"Public, pay-as-you-go pension system benefits are becoming increasingly unsustainable as fewer workers are supposed to support increased number of retirees in the near future," he said.

"This paper highlights that private pension schemes face very similar challenges as ageing reduces asset prices."

Financial stability

These headwinds for asset prices may also affect financial stability.

"Advanced economies, households, private institutions and the public, have accumulated substantial debt in the past few years. The results of the paper suggest that the assets financed by this debt could come under long run pressure. In particular, long run asset price headwinds could complicate the unwinding of leveraged financial positions," Takats said.

He said the results of the paper were also relevant when thinking about the sustainability of government debt.

"Two ageing related effects on government fiscal positions are well-understood. First, ageing will increase government expenditures, especially pension and health care spending. Second, ageing will slow economic growth as labor supply growth slows and in many cases reverses. Both of these factors will exacerbate government debt sustainability challenges."

Long run interest rates to rise

Takats said his paper highlighted a third negative effect.

"Lower asset prices imply that long run interest rates will face upward pressure in the future. These higher long term interest rates would make debt sustainability even more challenging," he said.

"In sum, this paper found that ageing is likely to affect future asset prices substantially negatively, though asset price declines, let alone a meltdown, are unlikely. The impact seems to be strong enough to think about its implications in pension provision, financial stability and government debt sustainability."

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.