By Bernard Hickey Finance Minister Bill English has pointed to a massive structural deficit in the government's finances and has called for a debate that asks some 'searching questions' about how to reform the government and the economy to improve New Zealand's growth rates. English told interest.co.nz in an interview that Treasury and the government were now coming to grips with the depth of the challenge in the decade ahead, given slow global economic growth, New Zealand's structural problems and the prospect of years of borrowing and deficits.  The 2009 budget had been written in a short period and had been designed to deal with the short term problems caused by the global financial crisis. Coming budgets would have to deal with the structural issues facing the economy, English said. "The harder we look at the way the world has changed, it's becoming increasingly clear that we won't have the same benign conditions we've had in recent years, and we won't have them for a long time," Finance Minister Bill English told interest.co.nz in a phone interview. "When you look at New Zealand's imbalances, they are larger and more embedded than we realised. We are going to have to ask some searching questions about what's required to achieve our ambitions of closing the gap with Australia," English said.

The 2009 budget had been written in a short period and had been designed to deal with the short term problems caused by the global financial crisis. Coming budgets would have to deal with the structural issues facing the economy, English said. "The harder we look at the way the world has changed, it's becoming increasingly clear that we won't have the same benign conditions we've had in recent years, and we won't have them for a long time," Finance Minister Bill English told interest.co.nz in a phone interview. "When you look at New Zealand's imbalances, they are larger and more embedded than we realised. We are going to have to ask some searching questions about what's required to achieve our ambitions of closing the gap with Australia," English said.

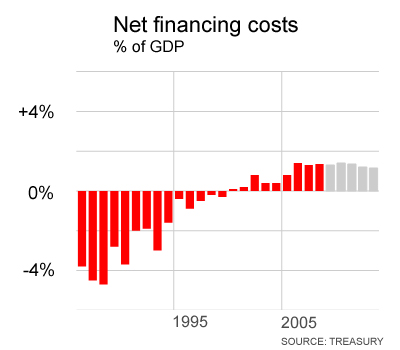

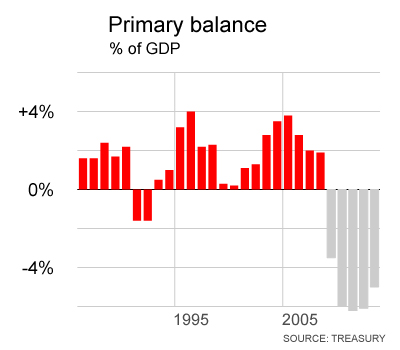

English referred to a measure of the government's structural position called the 'Primary Balance' , which extracted financing costs of debt and income from state owned assets and funds from the budget position to get a clearer picture of the government's core spending and revenues. English presented the measure to the Finance and Expenditure Committee (FEC) this week along with an analysis showing that output from the traded sector of the economy (exporters and companies competing with importers) stalled around 2004 and was now falling. Meanwhile, the non-tradeable sector of the economy (health, education, social services, electricity, construction, housing, communications and government) had continued growing output strongly.

English referred to a measure of the government's structural position called the 'Primary Balance' , which extracted financing costs of debt and income from state owned assets and funds from the budget position to get a clearer picture of the government's core spending and revenues. English presented the measure to the Finance and Expenditure Committee (FEC) this week along with an analysis showing that output from the traded sector of the economy (exporters and companies competing with importers) stalled around 2004 and was now falling. Meanwhile, the non-tradeable sector of the economy (health, education, social services, electricity, construction, housing, communications and government) had continued growing output strongly.  This raised questions about whether the non-competitive and state-owned parts of the economy had grown at the expense of the export earning sectors, meaning the current account deficit had deteriorated sharply. The combination of the two analyses presented a sobering and unsustainable outlook with the non-tradeable sector continuing to 'monster' the tradeable sector, creating twin current account and budget deficits that would suppress growth for years to come. Essentially, the wealth redistribution and consumption parts of the economy were overwhelming the wealth creation and the production parts of the economy.

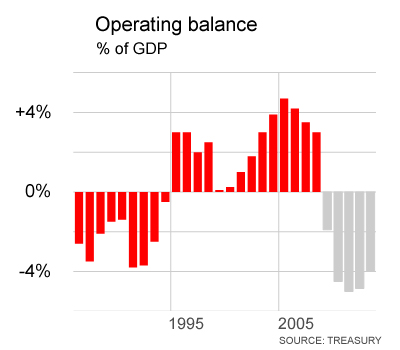

This raised questions about whether the non-competitive and state-owned parts of the economy had grown at the expense of the export earning sectors, meaning the current account deficit had deteriorated sharply. The combination of the two analyses presented a sobering and unsustainable outlook with the non-tradeable sector continuing to 'monster' the tradeable sector, creating twin current account and budget deficits that would suppress growth for years to come. Essentially, the wealth redistribution and consumption parts of the economy were overwhelming the wealth creation and the production parts of the economy.  The Primary Balance analysis showed the budget had been in deficit for only two years in the early 1990s once debt servicing costs were extracted. Since then the budget had been a structural surplus position up until 2009. The outlook was for structural deficits of 5% or more of GDP from 2010 onwards, which was far bigger than the deficits in 1991 and 1992 that prompted the 'Mother of all Budgets' and significant government reform. This analysis suggested that the scale of the budget deficit problem confronting the government is twice as big as that facing Ruth Richardson when she took drastic action in the "mother of all budgets" in 1991 to reduce entitlements and bring in asset sales to rectify the problem. However, once the tough medicine was taken, the economy and the government's fiscal position improved fast and significantly. This time the economy also faces the tradeables and non-tradeables imbalance that is making it very difficult to reduce New Zealand's chronic current account deficits. English pointed to the comments in a speech by Treasury Secretary John Whitehead as the beginning for a debate about structural reform that needed to be had. Here's what Whitehead said in the speech.

The Primary Balance analysis showed the budget had been in deficit for only two years in the early 1990s once debt servicing costs were extracted. Since then the budget had been a structural surplus position up until 2009. The outlook was for structural deficits of 5% or more of GDP from 2010 onwards, which was far bigger than the deficits in 1991 and 1992 that prompted the 'Mother of all Budgets' and significant government reform. This analysis suggested that the scale of the budget deficit problem confronting the government is twice as big as that facing Ruth Richardson when she took drastic action in the "mother of all budgets" in 1991 to reduce entitlements and bring in asset sales to rectify the problem. However, once the tough medicine was taken, the economy and the government's fiscal position improved fast and significantly. This time the economy also faces the tradeables and non-tradeables imbalance that is making it very difficult to reduce New Zealand's chronic current account deficits. English pointed to the comments in a speech by Treasury Secretary John Whitehead as the beginning for a debate about structural reform that needed to be had. Here's what Whitehead said in the speech.

Without changes to the tax system, there is a real risk that the government's revenue base will be unsustainable in the medium term, given growing competition for production factors and an aging population. More broadly, the tax system as it is currently structured does not seem fit for growth. The mobility of production factors "“ especially skills and capital "“ is of particular relevance to New Zealand's tax system and economy. New Zealand has one of the most internationally mobile labour forces in the OECD, and we have very high demand for inward investment. Our tax system should be encouraging investment to keep coming here and skilled people to keep staying here. Unfortunately that doesn't appear to be the case at the moment. A key priority has to be reducing effective marginal tax rates and increasing the rewards for effort. There is a growing view that the high mobility of our skills base means high personal income taxes are especially harmful for New Zealand's growth and productivity. There is also growing evidence that productivity is being held back by high corporate tax rates. New Zealand's company tax rates are at the upper end of the scale by the standards of the OECD and other open, small economies. With average OECD rates trending down, keeping our corporate tax rates competitive will be a priority. The pressure on us will be even stronger if the review of Australia's tax system currently underway leads to further company tax cuts across the Tasman. Another major component of a tax reform strategy should be shifting investment incentives, by taxing returns to capital in a more even-handed way. And at the risk of being chased down by an angry crowd with pitchforks and flaming torches, yes this should include consideration of moving the boundaries to tax more capital gains "“ for example on investment property - and shifting more of the tax base towards consumption. I know there is a lot of passionate debate on this matter, but capital gains or property taxes would be beneficial for encouraging investment in productive activity. A more complete capital income tax base reduces the impact of tax distortions on investment decisions, thereby improving the allocation of capital in the economy. It also improves fairness, and provides revenues that can be used to reduce overall income tax rates. Greater reliance on consumption tax "“ aligned with reduced income and corporate tax rates "“ should help strengthen incentives for savings. If we look at this at a high level, shifting from a system that relies heavily on income and corporate tax towards one that is weighted more towards taxing consumption "“ and bringing untaxed, or under-taxed, income-earning activity into the tax net "“ such a shift would better support higher productivity and growth. It would help address the sustainability challenges and tensions, where governments will increasingly grapple with competitive pressures to reduce taxes and demographic spending pressures to increase them. It would also help reduce our vulnerability to overseas events by reducing the pressure on the current account and thus external indebtedness. To be sure, such a shift would involve imposing challenges. But now, when hopefully we are at the bottom of the business cycle, is the most propitious time to make these changes.

A critical part of New Zealand's recovery programme will be bringing public accounts back into surplus as a matter of urgency. What is equally important is to ensure that over the coming years, our economy undergoes the adjustment and rebalancing it needs, with a strong focus on productivity and competitiveness. Now is the time to drive changes that will position New Zealand to come out of the recession stronger and better able to generate higher living standards.Overcoming the hurdle of geography and lifting productivity are not impossible tasks. They can be done. But they require New Zealand to set and achieve some high standards. In short, if we are to improve our economic performance and living standards significantly, we need to have institutions and policies in place across a wide range of areas that are not just good, but up with the best in the world. Our judgement is that many of New Zealand's current policy settings will not deliver the performance we need. I don't have time today to discuss them all, but one area I should touch on very briefly is the public sector and its role in a growth strategy. Taking resources out of the private sector to fund public services can create value "“ it may come as a shock that not everybody in the Treasury believes in leaving everything to the market! But it does come at a cost, and this cost rises the more you take out. This means we should set a very high threshold for additional public spending, if we want to provide both social benefits and sustainable economic performance. Otherwise, poor value and excessive spending acts as a tax on the competitiveness of the tradeables sector. The first salient point from this work is that we have underestimated the importance of people flows for growth. New Zealand relies heavily on these flows, not just to meet our labour needs but also for the exchange of ideas and innovation. All of our population growth, and half of our employment growth, between 1996 and 2006 was due to inward migration. And we have one of the highest rates of foreign-born residents in the OECD "“ almost one in four people living in New Zealand. The Treasury thinks there is scope to make much more of the advantages that can come from the movement of people both in and out of New Zealand. We could look at ways of shifting incentives, so that people sometimes study overseas and then come home, rather than the other way around. We could also enhance knowledge flows and innovation through stronger student and researcher exchanges. And we could do more to better integrate migrants, so that we can make the most of the skills, knowledge and connections they bring with them. The other pertinent finding from our work reinforces the point I made earlier: we think of New Zealand as an open country, but in some indicators we still lag other countries. Effective changes that could be put on the table include reducing the costs of Customs processes, removing all remaining tariffs, and lowering or even removing investment screening on all but the most sensitive of items. None of these on its own is a big hit, but they would add to the perception abroad that New Zealand is open for business. Never underestimate the importance of the signals we give.

Neville Bennett's article on the merits of a land tax, as used in Hong Kong, is also worth a read and generated significant comments when it was published on May 22 before the budget.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.