By Raymond Yeung*

China represented 18% of the world’s population in 2019. It is about to release its seventh census. Speculation that its population may have shrunk in 2020 prompted the National Bureau of Statistics to affirm in April that the population grew in 2020.

However, 21st Century Business Herald data shows numbers fell in eight out of 26 municipal cities. Population expert, Yi Fuxian, estimates the number of people in China was actually 1.26 bln as opposed to the highly cited 1.4 bln. By comparison, India’s is 1.3 bln. China may be losing its top place on the population league table and with it a comparative advantage.

Workforce

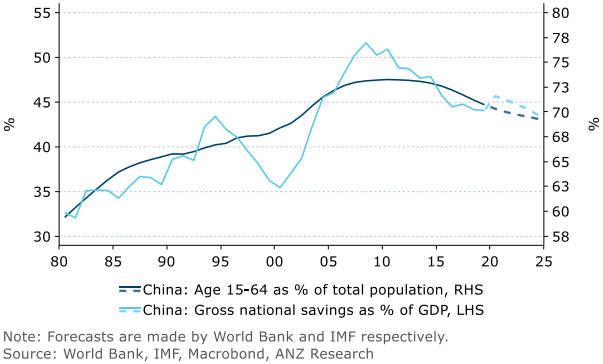

Significantly, 22% of the world’s workforce lives in China. This advantage, relative to other ‘post- demographic’ countries, emerged in early 2000 and peaked in 2011 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. China’s labour force is shrinking

By 2020, China’s workforce was back to 2007 levels (771m). Our projections show that its working age (15–64) population will be below the global average by 2035 (Figure 4). Policymakers are concerned that this, coupled with a property bubble, could pull China into a ‘Lost Decade’ (like Japan 1991–2001).

If birth-rate decline isn’t reversed by 2045, China will have a bigger share of elderly people than the US, and by 2050 its demographic dividend will have all but vanished.

Competition

Changes in the global workforce will shift supply chains, savings capital and technological positioning.

President Biden said in his first speech to Congress that the US is, “in competition with China and other countries to win the 21st Century.” Plans to invest in semiconductor manufacturing and other advanced technology are a hurdle to China’s tech aspirations. The loss China’s population advantage over the US (or other immigrant-friendly countries) will weigh on its competitiveness.

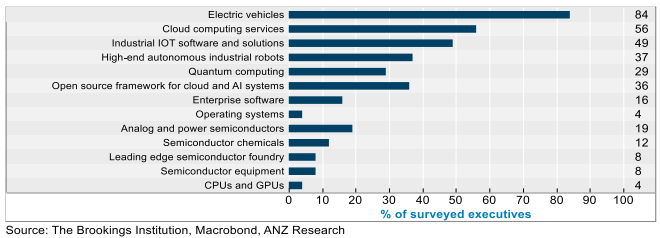

Figure 2. China-US race for technological superiority*, by segment

*Executive survey on sectors where China’s market share will be among the world’s top three by 2025.

Finance

China’s high national savings rate has fuelled investment-driven growth for over two decades. Commercial banks and the shadow banking system have recycled these savings into credit. In economic theory, retirees do not generate income, so as the working-age population declines, so will the savings pool. And that will have knock-on effects.

Reduced capital supply China’s savings have been a major source of capital for investors including funding US debt. As Ben Bernanke pointed out, China’s national savings contributed to global imbalance. The demographic trend bodes ill for the sustainability of this dollar recycling process. And, as China shifts to a techno-yuan regime to regain monetary policy autonomy, the US and China are likely to head towards a period of financial decoupling.

Advanced economies with ageing populations have seen very low domestic returns on investment, prompting their institutional investors to chase yield in the offshore market. An ageing China may also fall into a low-yield environment in a similar fashion. If China’s population becomes comparatively older than the US’s by the middle of this century, the direction of financial flows will become very interesting.

Figure 3. China’s working age population and savings rate

Demographics

In March, the People’s Bank of China noted some worrying demographic trends and urged the removal of birth restrictions as well as promoting higher savings.

Theoretically, lifting the retirement age would encourage more savings, but authorities also need to deleverage and curb the demographic impact on debt sustainability.

Recognising the urgency to act, Chinese authorities are upgrading the economy. Increasing productivity to maintain the rise in value-add, which is critical to supporting wage growth and consumption, is a theme in the “China 2035” vision.

In the “New Era” development plan, President Xi set 2035 as the target date for becoming a “modernised socialist” society, and China’s demographic profile coincides with that timeline.

Figure 4. China’s demographic profile coincides with Xi’s proposed timeline

Raymond Yeung is the ANZ chief economist for Greater China. He is based in Hong Kong. This is an edited version of ANZ's China Insight originally published on 3 May 2021.

12 Comments

They're making the same mistake the West has. And making the same misunderstandings of things like 'productivity'.

Resources per head are the true wealth - indeed without them there is nothing, and with more people there is less per person.

Truly there will be a competition between the US and China - but it won't be about 'productivity'- it'll be over who gets what's left. We need to be past listening to this kind of thing - should have been past it discussion-wise about 40 years ago

"Resources per head are the true wealth"

Simplistic. We can do more with less now. We're wealthier even with less resource consumption.

A local example - I no longer need to travel to work, I require less resources. Yet I'm wealthier in every way measurable. The computer I use to generate wealth was built with less resources and consumes less energy than a machine from 20 years ago, yet it's factors more powerful. If I need high powered server resources, I don't need my company to procure and host a stack of expensive hardware. I can share compute resources with other companies in highly efficient data centers, all over the globe, wherever those resources are cheapest.

When we need more material resources, we'll find them elsewhere. Energy is abundant.

Which explains beautifully why we so much less landfill now.

I think you are kidding yourself

Same old circular mistake. He thinks having no population growth is bad - because ummmh - it's not growing.

A different demographic profile ain't bad. It's just different.

"22% of the world’s workforce lives in China."

Well, it's only fair then that they make most of the stuff for us.

Oh, here we go again, unless we are breeding like rabbits disaster will befall us.

Will they ever learn?

It's why most economists should be kept in locked, padded rooms, with beans to count and away from decision making processes. Chuck in the religious cranks for good measure!

And the sycophantic finance media.

:)

(Capitalism seeking cheap labour) Oh well, off to India, then on to Africa, that should get us through the next 50 years, then back to the Americas for the next round?

Automation will go some way to picking up the gap. Renewable energy, 3d printing, AI, robotics. Off-shoring labour will look silly in 50 years.

Nothing like a bit of genocide to get that birth rate down.

China will get bodies from Africa. Africa is China's China.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.