By Xavier Waterstone*

KiwiSaver, originally envisioned as a cornerstone of New Zealand’s generational prosperity, was created to encourage saving for retirement, implicitly acknowledging a future where the public pension (NZ Super) would no longer be able to adequately provide for an ageing population. Beneath this notion of what KiwiSaver was designed to achieve lies a deeper narrative on taxation and contributions, shaping outcomes which contrast starkly with Australia's more pragmatic system.

Despite being critical to the financial wellbeing of all New Zealanders, the structure of our retirement savings system, or ‘KiwiSaver’ as it is commonly known, receives limited scrutiny and lacks some commonsense measures to improve the outcomes it produces for members. What attention KiwiSaver does get tends to be about fees. While fees make for an easy bone of contention because of their visibility, their effect pales in comparison to the much larger impact of taxes and contributions.

This article unpacks how New Zealand’s contribution and tax regime for KiwiSaver results in poorer outcomes for savings balances in retirement, using Australia’s superannuation system as a comparison.

What quickly becomes evident is the disadvantage working Kiwis are at versus our counterparts across the ditch when it comes to saving for retirement; and the need for meaningful reform to make the KiwiSaver system better fit for purpose.

From a sovereign point of view, the current system generates more tax revenue up front, but at the cost of a greater funding burden for the safety net (NZ Super) in the future. The main reason for this is deadweight loss from a tax regime that takes away compounding power from individual contributions, which hampers long-term accumulation of KiwiSaver balances.

***

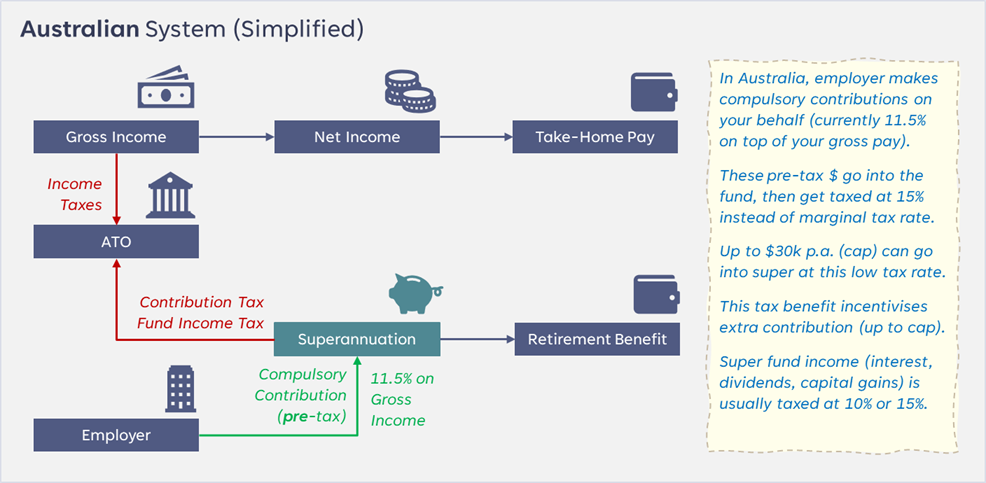

To give some initial context on how this deadweight loss is created, we first need sketches outlining how the mechanics of the two systems work. For Australia, the only relevant taxing point in our simplified example is the superannuation fund itself. This is because contributions to the fund are effectively taxed inside the fund as a ‘stream’ of fund income:

In New Zealand however, there are three relevant taxing points. There is the KiwiSaver fund itself for fund income, then additional taxing points for individual contributions, which are paid out of net income (i.e. income tax is taken out first), and employer contributions (where employer superannuation contribution tax or ‘ESCT' is taken out first). The upshot of this is that tax leakage on contributions happens outside the fund.

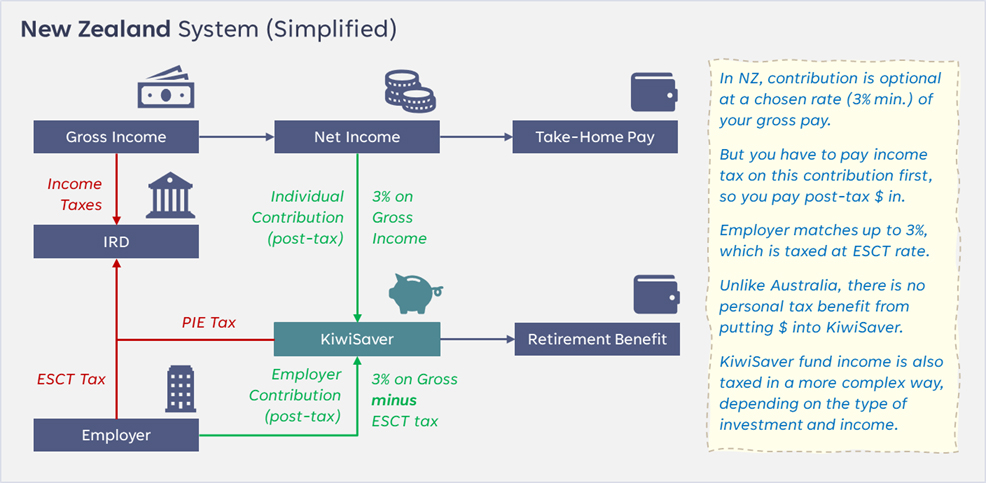

To supplement the sketches, the table below shows a side-by-side comparison of the key features underlying the two countries’ retirement savings vehicles:

Though it may not be immediately obvious, New Zealand’s non-concessional taxes on contributions, coupled with a weaker regime that doesn’t compel or incentivise contributions, results in poorer outcomes, with Kiwis’ nest eggs far smaller than our cousins across the ditch.

To illustrate this, what follows is an exploration of the major differences between the KiwiSaver and Australian Superannuation systems, using scenarios of how various aspects of tax and contribution impact the level of retirement savings accumulated over a working career.

To make the breakdown easier to follow, it has been written as a case study of ‘Sam’:

- Sam has just finished studies and training at 22, and has taken a role earning $50,000 gross, which increases at 3% p.a.

- Sam elects to contribute 3% to KiwiSaver, which is matched by the employer

- Sam continues to work and contribute to KiwiSaver until retiring at 65

- Sam’s KiwiSaver fund delivers a constant return of 6% p.a. (before tax)

- KiwiSaver Investment returns are taxed at an effective rate (ETR) of 8.1%

- Because the application of tax in KiwiSaver is quite complex (PIE tax regime), an effective rate, based on the total PIE tax paid as a portion of gross income across the KiwiSaver system in the 10 years to 2023 is used instead

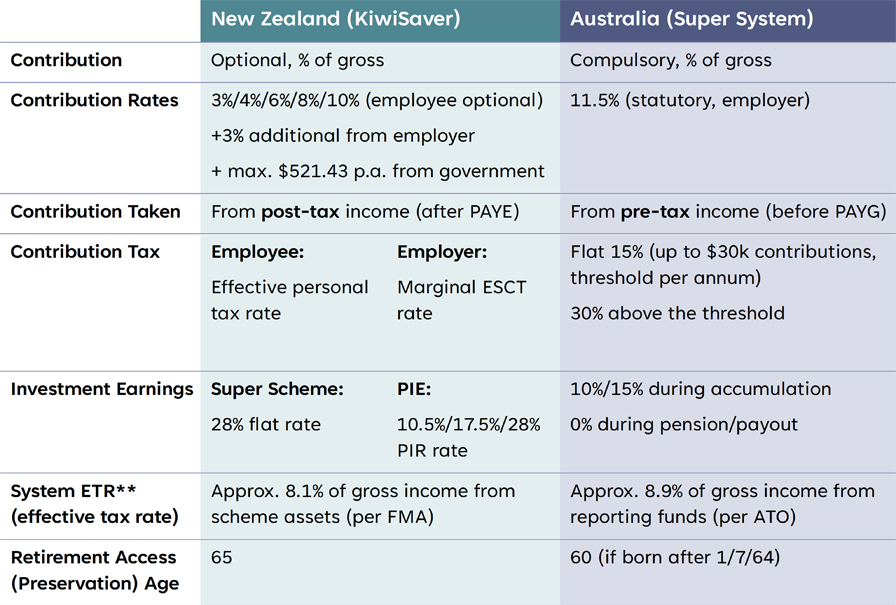

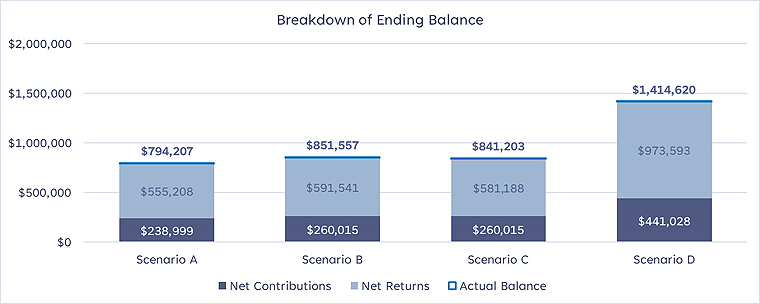

Scenario A: Status Quo (prevailing NZ tax rates & KiwiSaver system)

Under New Zealand’s current tax and KiwiSaver regime, by the age of retirement, Sam accumulates a KiwiSaver balance of approximately $793,000. This is comprised of (rounded):

- +$322,000 gross pretax contributions (total of employee, employer, and government)

- -$83,000 tax on contributions (with effective tax rate applied to individual)

- +$603,000 pretax investment returns

- -$49,000 tax on investment returns

Assuming Adrian Orr’s successors manage to hit the 2% midpoint of their target inflation range in the long run, this circa $793,000 future nest egg would be worth roughly $339,000 in today’s dollars. At a point-in-time rate of $3,000 per month, that’s about 9 years of living expenses.

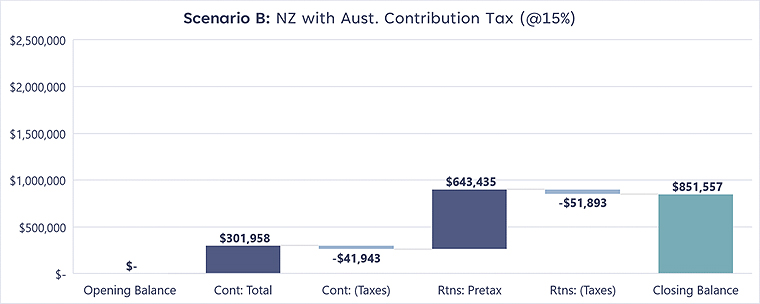

Scenario B: Status Quo, but contributions taxed like Australia

In the second scenario, we assume that instead of effectively taxing employee/employer contributions at the individual’s effective income tax and ECST (employer contribution tax) rates, we instead use Australia’s prevailing 15% tax rate on retirement contributions. This change results in Sam’s lifetime balance improving by about 7% or $58,000 to roughly $852,000, broken down as:

- +$302,000 gross contributions (less pay-away required due to lower tax)

- -$42,000 tax on contributions ($41,000 less tax)

- +$643,000 pretax investment returns (an extra $39,000)

- -$52,000 tax on investment returns ($3,000 more tax)

Not only does Sam get the benefit of larger net contributions due to a lower tax take going in, but there is a very important knock-on effect on compounding. The cumulative effect of contributions going in with more ‘firepower’ over forty-plus years is that Sam’s compounding of investment returns gets magnified by the larger regular deposits.

Even though some of this additional return is lost to tax, the impact is still meaningful. Viewed another way, New Zealand’s higher tax leakage* on contributions vs Australia’s (concessional rate, for most taxpayers) penalises Sam’s compounding power by around $40,000 (in addition to the higher contribution tax by itself).

Rounding off this scenario, Sam’s $852,000 future nest egg would be worth some $363,000 in today’s dollars, or 10 years of living expenses at $3,000 per month, again assuming 2% annual inflation.

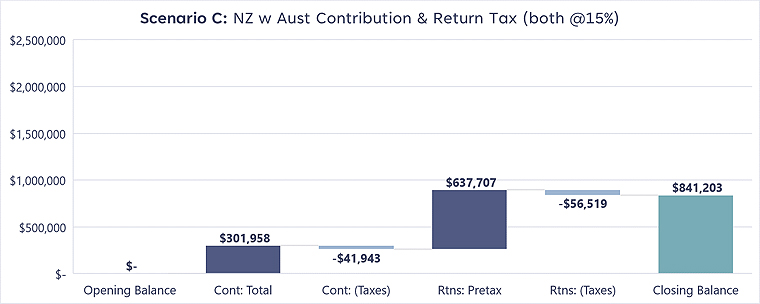

Scenario C: Status Quo, both contributions & returns taxed like Australia

For the third scenario, we make an additional change, and apply Australia’s slightly higher 8.9% effective tax rate or ‘ETR’ on rate on investment returns, instead of the historical 8.1% experience in New Zealand. We are now simulating Sam’s retirement balance as if Australia’s tax treatment applied to both contributions and returns. The resulting nest egg of approximately $841,000, made up of:

- +$302,000 gross contributions (same as Scenario B)

- -$42,000 tax on contributions (same as Scenario B)

- +$637,000 pretax investment returns ($6,000 less than Scenario B)

- -$94,000 tax on investment returns ($5,000 more tax than Scenario B)

While applying Australia’s tax experience on returns appears to dilute fund income, the takeaway here is that because we are using effective tax rates for the whole system instead of the individual settings, it isn’t conclusive that NZ’s taxing regime on returns is more favourable than Australia’s. In NZ for example, PIE tax can be applied at up to 28%, but only applies to some types of investment income, whereas in Australia, a flat tax of 10%/15% is generally applied, but only on interest/dividends/rent earned and when capital gains are realised.

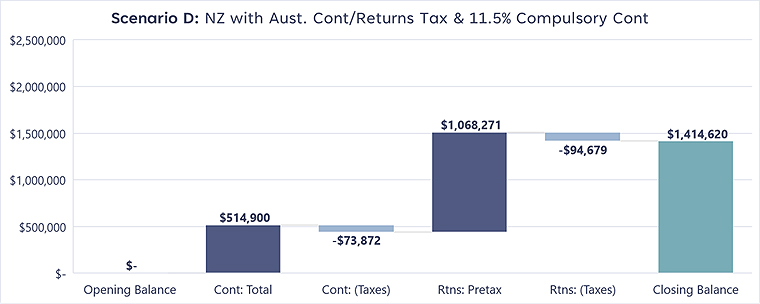

Scenario D: Australian regime applied to all taxes and contribution rate

For the final scenario, we make one last change, by lifting the contribution rate from NZ’s 6% (3%+3%) to Australia’s 11.5% which comes into force this year. This adjustment has the single largest effect on Sam’s balance, almost doubling the previous scenario to about $1,415,000, made up of:

- +$515,000 gross contributions (driven by higher contribution rate)

- -$74,000 tax on contributions (same % rate as Scenario C)

- +$1,068,000 pretax investment returns (a further $431,000 on top of Scenario C)

- -$95,000 tax on investment returns (same % rate as Scenario C)

As shown by the increase in closing balance, applying Australia’s 11.5% employer contribution rate has a major impact on the final outcome. While it results in Sam’s career gross contributions being $213,000 more, these extra contributions, along with cumulative investment returns, bump up the closing balance by a further $573,000. Using the same calculation as prior scenarios, this $1,415,000 future balance provides almost 17 years of living expenses at $3,000 per month in today’s dollars.

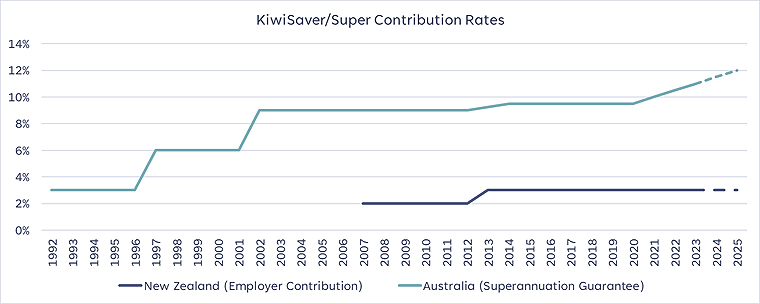

In connection with the material impact of contribution rates, it is noteworthy that Australia’s ‘Superannuation Guarantee’ contribution rate was also 3% in the distant past, but has ratcheted up over the years, and is mandated to be 12% in mid-2025. This, coupled with the earlier inception of Australia’s system, has seen superannuation steadily grow to A$3.7 trillion at the end of 2023 (~A$140,000 per capita) versus KiwiSaver at NZ$0.11 trillion (just ~NZ$20,000 per capita). In reality, because of the long accumulation lifecycle, even if NZ were to adopt Australia’s contribution rate today, it would take several decades before retirees withdrawing would see the full benefit.

***

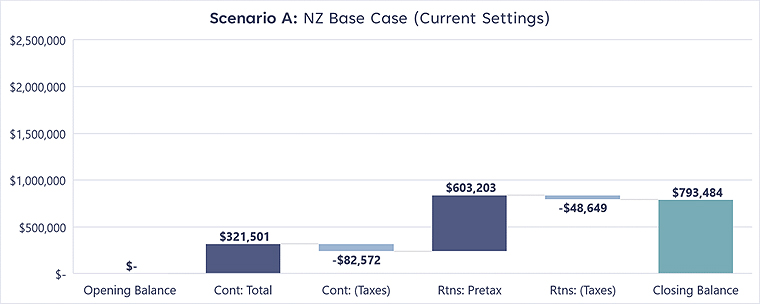

Bringing it all together, two key conclusions emerge. The first is apparent from the gap between Scenario A (current NZ system) and Scenario D (with the Australian regime applied) in the chart below.

If our hypothetical Sam was embarking on a career and considering retirement savings as one piece of the puzzle, the Australian system is far superior, and results in a nest egg 1.8x larger (or over $600,000 more) versus New Zealand. Beyond that there is also an earlier preservation (access) age, and the benefit of all superannuation earnings being tax free when Sam moves from ‘accumulation’ phase into ‘decumulation’ phase and starts drawing down.

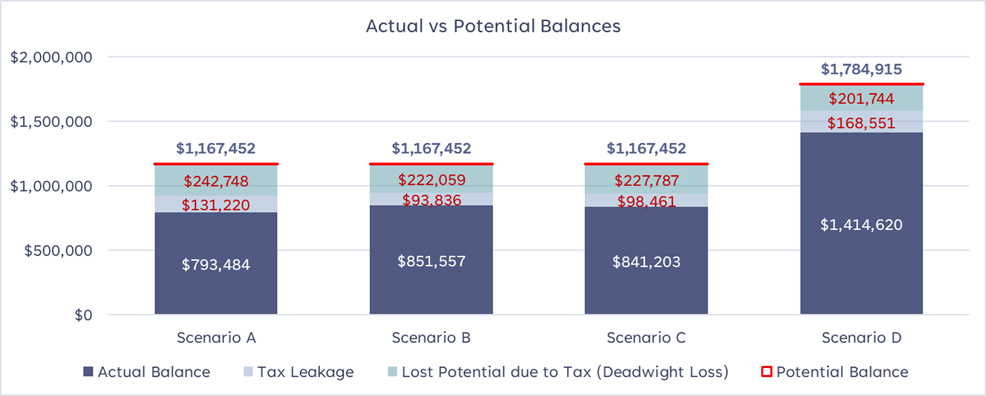

The second conclusion is less obvious, and has to do with both taxes and the deadweight loss caused by taxes hindering the compounding effect of Sam’s contributions and investment returns. Together, these two costs mean Sam’s ending balance in each scenario is less than what the potential balance could have been if there were no taxes. This gap tells us that NZ’s system (Scenario A) is inefficient versus Australia’s regime (Scenario D).

Put simply, in Australia, Sam’s actual balance is 79% of potential, whereas in New Zealand, it is only 68% of what it could be in a tax-free world. When translated into dollars, this difference gets magnified by the compounding effect of contributions. As is the case with potential salaries for many job roles, this dollar difference contributes both to the desertion of aspirational Kiwis across the ditch, and a larger liability for a future means-tested NZ Super as lower balances mean less self-sufficiency and greater reliance on the public purse. Importantly, the potential balance in NZ necessarily reflects the 3% personal contribution being grossed-up for tax that has already been paid on it.

Coming back full-circle, it is difficult to argue that our retirement savings system is fit-for-purpose, especially compared with our neighbours’ across the ditch. Not only do we have an absence of strong incentive to save, but the design of the system dilutes the ability of wealth which sits within KiwiSaver to compound effectively for the future.

The system is unambiguously in need of reform, and whilst the recent retirement commission report puts forward some mild proposals, a bolder ‘shaken not stirred’ approach to recalibrate taxation and contribution settings is needed. As dependency ratios deteriorate due to an ageing populace, it is not a fait accompli that NZ Super will have the capacity to be a universal and adequate safety net generations from now, hence the need for stronger individual redundancy. A lower public funding burden also creates more future scope to reduce taxes, noting New Zealand’s more regressive brackets mean that the vast majority of earners pay a higher effective tax rate than they would in Australia.

Whilst there is inevitably a great deal of politicisation and conjecture around retirement savings, the proof is in the pudding, and perhaps we need less working group and more working model. The better outcomes underpinned by concessional tax and stronger contribution can already be seen across the ditch, but getting there requires the courage to accept some short-term pain for long-term gain, which is most always easier said than done.

***

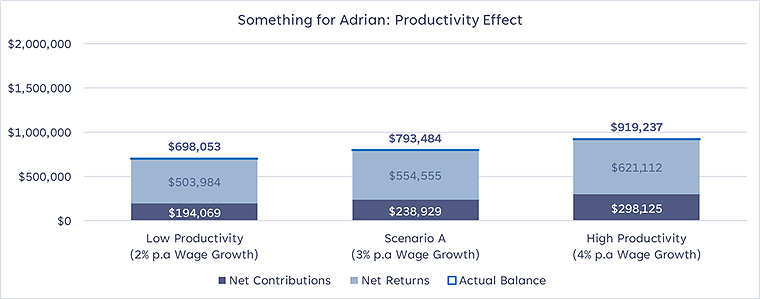

Bonus Scenario: The Productivity Effect

Online KiwiSaver balance calculators from providers are required to use FMA assumptions which include a 2% inflation rate to bring the future ‘nest egg’ value back into today’s dollars, and 3.5% for annual wage growth.

In the scenarios discussed above, the 3% p.a. growth for Sam’s wages is higher than the 2% midpoint of the RBNZ’s target inflation band. This extra 1% reflects productivity, i.e. that the more efficient use of labour and capital over time (due to upskilling, technology, experience etc.) enables wages to grow faster than inflation.

The economy-wide level of productivity also has a significant impact on KiwiSaver balances via the channel of wage growth. Below is a bonus chart which shows a low productivity scenario, where wages only grow at inflation; along with a high productivity scenario where wages can grow at twice the rate of inflation.

The significant difference between the two illustrates the contrast between an economy which can generate growth by using its resources more efficiently and adding value to its outputs, versus an economy that can’t grow except by using more resources. New Zealand has recently fallen more into the latter camp, the decline in real GDP growth per capita reflecting productivity going backwards.

***

Looking for an award-winning KiwiSaver scheme? Find out more about the QuayStreet KiwiSaver funds by visiting quaystreet.com

Disclaimer & Footnotes

The author is Head of Australasian Equities for the QuayStreet Funds and QuayStreet KiwiSaver Schemes. Smartshares Limited is the manager and issuer of those schemes and a product disclosure statement for each of them is available from https://quaystreet.com/documents

This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should it be construed as, investment advice for any person. The scenarios in this article are only intended to broadly map out some key disparities between retirement systems. To prevent the presentation being excessively complex, some simplifying assumptions have been made, which include continuous taxation of returns at respective ETRs, holding income/ESCT tax brackets and rates constant, and addressing the issue of NZ’s taxing point by grossing-up KiwiSaver contributions with tax to better show the actual tax leakage that occurs.

These assumptions mean the dollar values outcomes will differ from actual experience, but notwithstanding, shouldn’t impact the qualitative conclusions reached in comparing the two systems.

* On incomes higher than approximately $30,000 in NZ, the combined income tax and ACC earner’s levy results in effective tax rates higher than Australia’s 15% concessional contribution rate.

**Because of the enormous complexity around how different types of income within each country’s retirement systems are taxed, effective tax rates or ‘ETRs’ have been applied based on tax incurred historically:

- For KiwiSaver, ETR is taxation over 10 years as a % of gross income from scheme assets over the same period, using latest available FMA data (to 2023).

- For Australian Superannuation, ETR is calculated the same way using the latest ATO data (to 2021) which encompasses both large APRA-regulated entities and self-managed funds.

* Xavier Waterstone is Head of Australasian Equities at QuayStreet Asset Management.

13 Comments

This article is now open for reader comments on the issues raised.

..wake up turn on heating, read article, wonder what housing market doing in Perth

What QuayStreet's Xavier Waterstone is telling us, as economist Andrew Coleman does elsewhere, is that Kiwis are bad squirrels who run and jump and play and spend all summer and autumn with no heed of the winter to come.

Although Xavier Waterstone's advocacy of anAustralian-style KiwiSaver with compulsory, high, barely taxed contributions to equally barely taxed funds would be good for fund managers, it would not be good for New Zealanders.

Kiwis make bad squirrels; we don't save enough, that's true. But we also don't pay enough tax. Not only not enough income tax (I think the Aussie top rate is 45%), but we lack a universal land tax, a capital gains tax, inheritance tax and gift tax.

There's no money. An underfunded state health service forces us to pay privately for health care (if we can afford it, otherwise stay ill), the roads are full of pot holes, the water supply, sewerage and drainage are disintegrating. We all know the stories.

The state needs the tax on KiwiSaver contributions, and the tax on KiwiSaver earnings, that Xavier Waterstone would like to see abolished.

A problem with KiwiSaver is its inevitable inequality: those who can save do; those who cannot don't. Many people spend every dollar they earn paying for the roof over their heads, the electricity to heat their home, and to feed and clothe the kids.

KiwiSaver already divides the haves who can save from the have-nots who cannot. If the taxes on KiwiSaver contributions and earnings were reduced or abolished the pots of the haves would grow larger and faster as Xavier Waterstone describes, leaving the have-nots ever further behind.

There is a fair solution. It lies in our existing NZ Superannuation, universally available from the age of 65, and in the NZ Superannuation Fund to pay for it in the future instead of relying on current taxation. New Zealand needs to hugely increase the state's contribution to the NZ Superannuation Fund (which of course ought not be paying tax on its earnings), by introducing all those taxes we now lack.

In essence, the solution is for all squirrels to contribute nuts into one big paataka according to their various means, so that when winter comes there will be enough to be distributed equally to all.

It is a solution that will be cold comfort to fund managers, unless they are allotted a portion of NZSF investments to manage, but it offers a fairer way forward for New Zealand.

But what happens if the squirrels who collect the most nuts go somewhere else JT, then the whole thing just gets hollowed out doesn't it?

Kiwis pay plenty of tax. We pay personal tax, GST at 15% - comprehensively on all goods and services. Australia is 10% on some goods/services and the very high personal rates were dropped to reflect this when we changed from the old regime of taxation of up to 40% on what they called luxury goods (including female personal necessities). We pay ACC levies. We pay tax on interest and shares including an assumed amount on overseas shares irrespective of whether that rises or falls. We pay fuel taxes per litre or RUC per distance. We pay excise taxes eg on alcohol, duties, a range of full and part charges on a user pays basis for services like seeing a GP or getting a passport. We do pay land/property taxes in rates paid to local government. Businesses and employers pay a range of taxes, including FBT for anything like a car or insurances for employees and ESCT on Kiwisaver. Trusts are taxed at 39% now. We have a capital gains tax regime where people sell or develop property for profit pay tax, this can even catch the family home if they don't fit the narrow exceptions. If you need rest home/hospital care later in life, this is means tested and they will take your assets leaving only about $14000, enough to pay for legal and funeral expenses but nothing much else.

More than half your income is gone to tax, savings is whatever you have left to yourself after paying all the other costs to live. I don't think it is sustainable at all to say there isn't enough tax paid, are we going to be allowed to build anything up for a comfortable retirement once the extra tax is laden on? The elderly are definitey far worse off if they don't have a house when they retire and that's even if there is still a mortgage on that. You could strip people of everything but the government would not be able to handle the burden. It doesn't make sense in a recession to do this or the government tax people more, leaving less and less to live on, actually the best thing to do is suspend contributions to the fund until times are better. Once that happens, let people keep more of their income so they've got a bit left over to save and invest for their future.

High compulsory superannuation contributions are all very well and good, and it's helping build Australia. However: there are so many people on good incomes, living from paycheck to paycheck becasue of their high debt servicing, that there isn't much of anything left over to contribute. To reduce debt by having smaller mortgages would require a drop in the property prices, the introduction of CGT on everything except the family home to make property a much less attractive speculative instrument - while somehow making any change a just one, so property investors don't lose too much equity in what really is likely their super fund...amongst a bundle of other changes.

It feels like we've painted ourselves in to a corner that's going to take some very good management to get us away from the low-income, low productivity place we're becoming - or have become - without pulling the place down on top of us.

No amount of managed funds are going to help that if the underlying inconsistencies are not fixed.

Game theory suggests first out best dressed, a drop in NZD so holding offshore assets = better, not good for house market.

Also when comparing the two schemes, you should mention that a KiwiSaver account can be raided to take out a deposit on a home, while the Australian one is limited to a single $15k withdrawal. This destroys the KiwiSaver retirement account as a 20 year old who contributes for 10 years but withdraws the full amount at 30, and then resumes contributions for the next 40 years, still ends up with LESS than the 20 year old who contributes for 10 years and then stops contributing altogether for the next 40 years. I wish people realised the maths behind this fact. You should not be allowed to withdraw funds from KiwiSaver if it is to genuinely be a retirement savings plan, and not just a general savings account.

I really appreciate Xaviers comparison of the two systems which most NZers may be unaware of, esp how Australia tax on super is an Encouragement to save v NZ which is a discouragement. Thank you for the analysis as many in NZ are in denial we have a looming issue so believe a braver retirement commissioner and politician need to start a discussion on this.

Esp as 1.2 million or 40% of kiwisaver members don't contribute anything so miss out on employer contribution if working and govt $521 as well

(Michael Cullen couldn't help himself and ended up taxing employer contributions so we only get effectively 2% from our employers) - this limits the compounding effect dramatically compared to taxing at the other end

I was very disappointed with the bias in this article. I think its misleading and fails to account for Econ101 concepts adequately. Who would have thought a Kiwisaver provider wants more concessionary tax treatment?!

My main critique: The definition in the article for a 'deadweight loss' is wrong. A deadweight loss should be the loss of social welfare across the economy; not simply a loss to the investor. The analysis fails to account for the "benefit" to the government of having the extra revenue, which could be used (for example) to invest in the exact same asset allocation as the investor had, with the exact same income stream. I'm sure there is a deadweight loss but its quantity will be different to that calculated in the article and it is more likely to relate to govt inefficiencies, admin costs, compliance costs and changes in behaviour.

In a similar manner, the lost aggregate retirement savings do not account for the "gain" or improvement in the Crown's savings position.

The so-called deadweight "loss" is conflated with Sam's lost potential balance. The potential balance in scenario D is high (in part) because of a higher compulsory contributions rate (11.5%). What if Sam is hand-to-mouth? What if Sam is unable to fund a child's school books or trips? There are deadweight losses associated with compulsion that are not explored in the article.

Other minor critiques:

A) Strangely the Aus contribution tax (flat 15%) does not seem to be 15% in the scenario ($42k/$302k = 13.9%). Something else is obviously going on in the scenarios but is not explained.

B) Maybe I'm thick but I don't get why the gross contributions in Scenario B are less then A. The explanation is unclear to me: "less pay-away required due to lower tax"

While this is useful to compare like to like from a tax perspective I disagree with the final difference

To simplify and take out inflation and tax and empahsis the difference in contribution. Lets say someone earnt $50k for their whole career +3% employee +3% employer = a 6% contribution = $135k contributed over the 45 year career

But the 6% needs to be compared to a 14.5% contribution in Australia (it 3% contributed by employee + 11.5% contributed by employer = a 14.5% contribution) so the contribution would be 2.4 X greater at $326kand consequently the final number would be perhaps 4 X greater taking into account the compounding effect of a larger contribution on compound interest

Kiwis are lousy squirrels for sure. Play in the summer. Starve in the winter and wonder what happened.

a. National Super will break. It can't last.

b. Start a universal Kiwisaver at large inputs.

c. A phase in/ phase out system with National Super over thirty years.

d. No subsidy, but also zero tax, at entry, during or exit. It''s not an ordinary investment, it's a poverty avoiding social instrument.

e. To those who say they can't afford it. Well, you can't afford not to. We are not a rich country, there is no magic trick money source.

f. To the masters of investing who want to invest for themselves. Nothing stopping you. Do that as well. But you Kiwisaver is also there for you.

We already have a universal KiwiSaver: it's the NZ Superannuation Fund. What is needed is to fund it adequately to invest for the future. To do that we must either levy compulsory contributions on every dollar of everyone's income in the form of a hypothecated tax, or else introduce a capital gains tax on the sale of every asset including the family home, plus reimpose land taxes, inheritance taxes, and gift taxes.

By funding the NZ Superannuation Fund adequately, not taxing its earnings, and allowing it to continue to invest independently, the existing NZ Super will be perfectly capable of providing everyone equally with a pension far into the future.

Those with surplus cash could still invest additionally in their private managed funds, but they should do that without any state subsidy, and be taxed on their account earnings within those funds in line with their ordinary income tax, not, as now, with a top tax rate of 28%.