By Tobias Adrian, Vitor Gaspar, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas

Inflation-adjusted interest rates are well above post global financial crisis lows, while medium-term growth remains weak. Persistently higher interest rates raise the cost of servicing debt, adding to fiscal pressures and posing risks to financial stability. Decisive and credible fiscal action that gradually brings global debt levels to more sustainable levels can help mitigate these dynamics.

Public debt sustainability

Debt sustainability depends upon four key ingredients: primary balances, real growth, real interest rates, and debt levels. Higher primary balances—the excess of government revenues over expenditures excluding interest payments—and growth help to achieve debt sustainability, whereas higher interest rates and debt levels make it more challenging.

For a long time, debt dynamics remained very benign. That’s because real interest rates were significantly below growth rates. This reduced the pressure for fiscal consolidation and allowed public deficits and public debt to drift upwards. Then, during the pandemic, debt increased even more as governments rolled out large emergency support packages.

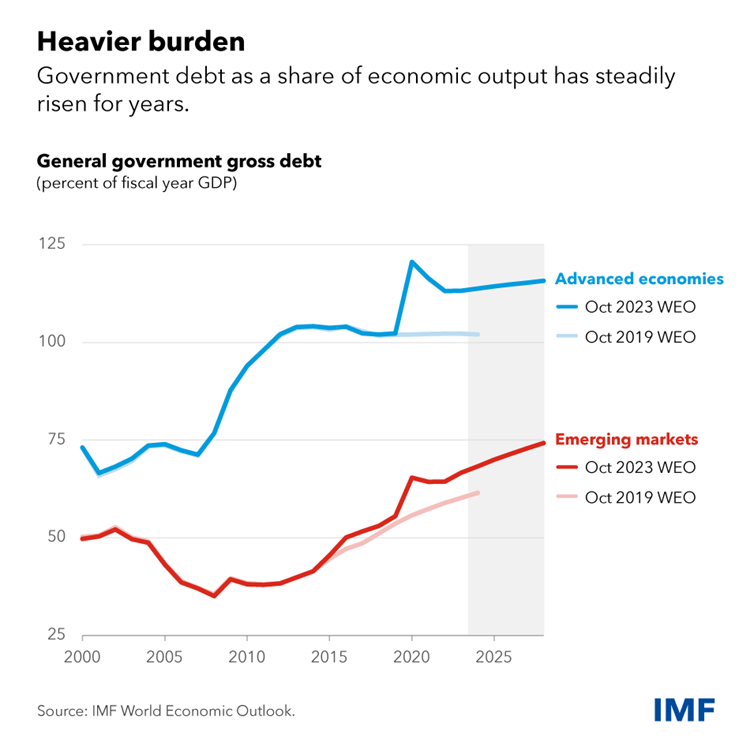

As a result, public debt as a fraction of gross domestic product has increased significantly in recent decades, across advanced as well as emerging and middle-income economies. It is expected to reach 120 percent and 80 percent of output respectively by 2028.

At the same time as we confront higher debt levels, the macroeconomic environment has become less favorable. Medium-term growth rates are projected to continue declining on the back of mediocre productivity growth, weaker demographics, feeble investment and continued scarring from the pandemic.

Against this backdrop, elevated real long-term interest rates could pose significant challenges.

Short- and long-term rates

Public debate has focused on the short-term real interest rate, known as r*, defined as the equilibrium interest rate at which an economy is operating at its full potential while keeping inflation stable. This equilibrium real interest rate has declined dramatically in recent decades driven by slow-moving, structural variables such as demographics, demand for safe assets, productivity growth, or the income distribution. As long as these factors continue on similar trajectories as before the pandemic, equilibrium rates around the world will remain very low as shown in an analytical chapter of the April 2023 World Economic Outlook.

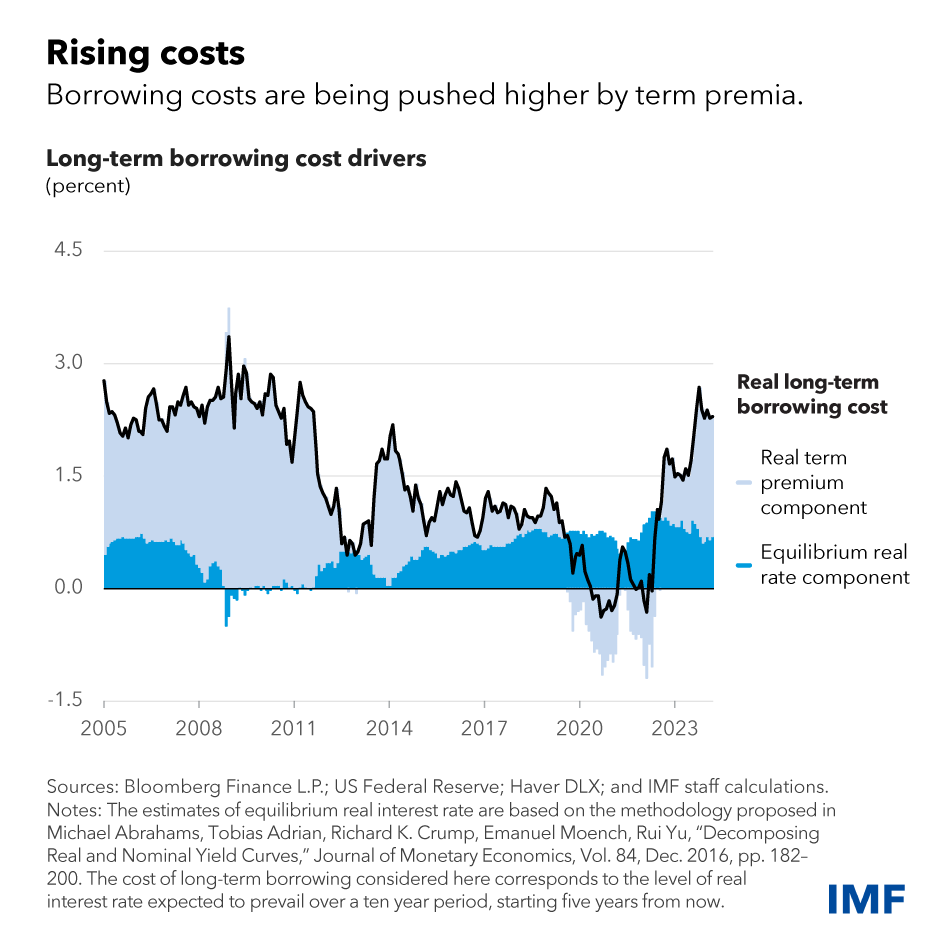

However, even if r* remains low, the real borrowing cost of government, household, and corporate sectors could be higher in the future. This is because they tend to borrow not for short periods, but longer term, and the associated long-term interest rates incorporate a risk premium—known as the term premium—that compensates lenders for providing funds for an extended period of time.

The dynamics of r* and long-term rates can be illustrated in the case of US Treasury bonds, which serve as global benchmark for fixed income markets. The dark blue bars show an estimate for the r* in the United States. This has risen slightly recently but remains at relatively low levels. By contrast, estimates of the term premium, the light blue bars, have risen more markedly over the past year. In fact, the United States Congressional Budget Office has recently warned of the rising debt burden, noting that it could put pressures on the cost of financing.

Longer-term real interest rates are therefore now comparable to their pre-global financial crisis levels in large part due to higher term premium, and there are reasons to believe that may persist:

First, the inflation fight continues. Even as central banks contemplate easing their policy stance, real rates will remain volatile for some time.

Second, the balance sheet normalization that major central banks have started, commonly referred to as quantitative tightening, may also contribute to higher real term premia by increasing the supply of longer dated securities that need to be absorbed by the market.

Third, the rise in interest rates also likely reflects expansionary fiscal policy and longer-term fiscal concerns, at least in some countries. Loose fiscal policy can contribute to higher interest rates, especially when inflation is high, by forcing central banks to tighten even more to achieve their objectives. Loose fiscal policy, if sustained, can also create investor doubts around long-term debt sustainability, leading to higher term premia.

The key point is that despite low equilibrium rates, borrowers in the United States and the rest of the world may face a new normal with significantly higher funding costs than in the past decade.

Financial stability

If improvements in governments’ primary balance cannot be achieved to offset higher real rates and lower potential growth, sovereign debt will continue to grow. This will test the financial sector’s health. First, the so-called “bank-sovereign nexus” could worsen. At high debt levels, governments have less capacity to provide support for ailing banks, and if they do, sovereign borrowing costs may rise further. At the same time, the more banks hold of their countries’ sovereign debt, the more exposed their balance sheet is to the sovereign’s fiscal fragility. Higher interest rates, higher levels of sovereign debt, and a higher share of that debt on the banking sector’s balance sheet make the financial sector more vulnerable.

The bank-sovereign nexus is spreading beyond advanced economies to developing economies and a few vulnerable emerging markets. For example, the median banking system in low-income countries now holds about 13 percent of the country’s sovereign debt, double the share 10 years prior.

What’s more, in a context of limited fiscal space because of high debt, pressures on monetary authorities to tolerate departures from price stability to support public finances or the financial system may rise. This may be especially relevant in countries with high public debt If this were to happen to systemically important countries, financial market volatility could also rise, increasing the cost of financing for businesses and households globally. Debt concerns that spill over to benchmark interest rates could in turn distort asset prices and impair market functioning.

Finally, financial stability could become strained in emerging markets with relatively weaker economic fundamentals, as high debt burdens make them much more vulnerable to capital outflow pressures, exchange rate depreciation, and increased expectations of future inflation.

Policy implications

Some key policy implications follow from the above considerations.

First and foremost, countries should start to gradually and credibly rebuild fiscal buffers and ensure the long-term sustainability of their sovereign debt.

It is easier to rebuild fiscal buffers while financial conditions remain relatively accommodative and labor markets robust. It is harder to do so when forced by unfavorable market conditions. Durable fiscal consolidation will also allow policy rates to fall faster, which should reduce any adverse effects on the macroeconomy. While a substantial fiscal consolidation is necessary, this is not a call for austerity. Too sharp a tack towards fiscal consolidation could backfire by pushing economies into recession. What is needed is for a credible first installment, followed by subsequent, gradual steps in the same direction.

Second, to preserve financial stability, stress tests should adequately account for the impacts on banks and non-banks of higher sovereign interest rates and potential bouts of market illiquidity. Upgrading market infrastructures to improve trading, price discovery, and market depth is also a key policy priority, even in the most liquid sovereign debt markets.

Third, structural reforms should not be postponed. By enhancing future growth, they are the best way to help stabilize debt dynamics.

Vítor Gaspar is director of the IMF Fiscal Affairs Department. Tobias Adrian is the financial counsellor and director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department. Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas is the economic counsellor and director of the Research Department. This article was originally posted here.

19 Comments

Second, the balance sheet normalization that major central banks have started, commonly referred to as quantitative tightening, may also contribute to higher real term premia by increasing the supply of longer dated securities that need to be absorbed by the market.

The Fed has been running QT for over 1.5 years now. The intent was to remove excess liquidity from the system - but it's not happening: - Jun 2022 reserves: $3.3 trillion - Jan 2024 reserves: $3.4 trillion We are witnessing a Sterilized QT. What's that? Link

Why is QT not removing liquidity Audaxes?

Public debate has focused on the short-term real interest rate, known as r*, defined as the equilibrium interest rate at which an economy is operating at its full potential while keeping inflation stable. This equilibrium real interest rate has declined dramatically in recent decades driven by slow-moving, structural variables such as demographics, demand for safe assets, productivity growth, or the income distribution. As long as these factors continue on similar trajectories as before the pandemic, equilibrium rates around the world will remain very low as shown in an analytical chapter of the April 2023 World Economic Outlook.

This is what Milton Friedman called the interest rate fallacy, and it indeed refuses to die. We can tell what monetary conditions are in the real economy, as opposed to financial liquidity, though the two can be linked, by the general level of interest rates. When money is plentiful, interest rates will be high not low; and when money is restricted, interest rates will be low not high. The reason is as Wicksell described more than a century ago:

[The natural rate-r*] is never high or low in itself, but only in relation to the profit which people can make with the money in their hands, and this, of course, varies. In good times, when trade is brisk, the rate of profit is high, and, what is of great consequence, is generally expected to remain high; in periods of depression it is low, and expected to remain low.

When nominal profits are expected to be robust, holders of money must be compensated for lending it out by higher interest rates. Thus, the same holds for inflationary circumstances, where nominal profits follow the rate of consumer prices. During the Great Inflation, interest rates weren’t low at all, they were through the roof well into double digits and higher by 1980. At the opposite end in the Great Depression, interest rates were low and stayed there because, as Wicksell wrote, the rate of profit was low and was expected to be low well into the future. High quality borrowers were given as much money as they could want while the rest of the economy was deprived of funds; liquidity and safety being the only preferences in what sounds entirely familiar. Link

lol ...The only emerging market NZ has is the next housing ponzi....lol

Not sure you understand the term "emerging market"

Pure, unadulterated reckonomics.

There is certainly quite a bit of 'reckons' there and some hard to pin down and somewhat nebulous concepts. But some bits are worth further consideration. I'll be re-reading again when I'm less tired.

I took it as a shot across the bows of the good ship USA (and a few others). Maybe along the lines of, "You are in unchartered waters - so reduce steam".

Governments that spend in their own currencies don't need to issue debt and it's only something that they choose to do and as a sop to the financial markets. https://clintballinger.com/2018/11/13/decouple-spending-from-bond-sales/

Public debate has focused on the short-term real interest rate, known as r*, defined as the equilibrium interest rate at which an economy is operating at its full potential while keeping inflation stable. This equilibrium real interest rate has declined dramatically in recent decades

I don't buy it. The inflation just showed up in asset prices. Fake growth, fake stability, fake news.

If only we lived in a world where asset prices could come back to earth as they naturally should. Instead we will have endless attempts to keep them inflated resulting in the price of everything else going up instead (with the exception of labour of course). Yes, yes, I know that's 'impossible' because it would cause a catastrophe. The whole economy feels like one of those 'too big to fail' scams these days.

If only we lived in a world where asset prices could come back to earth as they naturally should. Instead we will have endless attempts to keep them inflated resulting in the price of everything else going up instead (with the exception of labour of course). Yes, yes, I know that's 'impossible' because it would cause a catastrophe. The whole economy feels like one of those 'too big to fail' scams these days.

You have learnt well young Jedi

Asset prices drives the ability to borrow (inject more debt) and apparently makes us wealthy. The entire financial system is dependent on inflating asset prices and associated returns. Were it all to revert to something sensible the people believe they will be poor and will have lost wealth. Without a different approach it would all just repeat, as it has done for the past century.

Too sharp a tack towards fiscal consolidation could backfire by pushing economies into recession

Unfortunately for NZ, the starting point IS recession, even before considering fiscal consolidation.

Hmmmm. People saw low interest rates, stupidly borrowed heaps, interest rates go up, assets prices down….and now no money to spend. Seems fairly obvious things will be slow for a while during this shake down and rebalancing.

Govt debt as a share of economic output on the graph should scare many. Why is it that govt debt os carrying us through when we should be encouraging and enhancing the private sector SME’s to succeed.

At the current trajectory we will wind up a country with multinational chain stores and 3 landlords for the majority of the population (sarc)

Because we hoard "wealth" and create debt instead of encouraging the flow of money?

"Debt is money" plus usury is the problem. It's also merely a symptom of a deeper collective issue.

Every balance sheet has two sides and the government is on one side and the private sector is on the other and they mirror each other. When the government is in deficit then private sector must be in surplus and accumulating financial assets and so government debt is our savings held in the governments currency.

https://theconversation.com/how-government-deficits-fund-private-saving…

At the current trajectory we will wind up a country with multinational chain stores

Really? Why? Maccas I can understand. Why do MMCs want to build their businesses in NZ? What do we have to offer to Walmart?

Do MMCs try to build their businesses here? I get that we don't have the population base or is it too expensive for new entrants especially in the FMCG sector? Given some of the stories of Walmart maybe our employment laws are too tight for them?

I think the real issue is the rise of private equity/fund managers that just buy whatever they can for extraction purposes.

Then we have incumbents buying up competitors (continuing with the same brand) and creating an illusion of competition.

It used to be that a viable business depended on the quality of service, the relationship between proprietor and customer, which if positive garnered repeat custom and increased custom via positive word of mouth. We appear to have devolved into something more akin to farming the customer, some belief that the digital experience positively replaces customer service, and we are now servants to the market rather than the market serving us. Highlighted by your question "what do we have to offer Walmart?"

But the majority now seem ok with just ordering online more out of convenience (laziness? apathy?) with no relational value. Walk into a store and generally they feel bereft of positive energy. What have we wrought?

'By enhancing future growth, they are the best way to help stabilize debt dynamics.'

No shit? Really?

Project that graph of theirs - world growth, decline thereof - and ask why? (reducing availability of energy and resources, being the answer).

This is a permanent, and accelerating, reduction. Whither debt? Either default, or jubilee. Or increasing inflation, being a controlled default sort of thing.

Funny how detailed they get, while remaining so physically-ignorant.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.