By David Skilling*

Four years ago this month, early reports were coming through from China of a dangerous new virus in Wuhan. Over the next two years, large parts of the global economy were locked down or restricted.

But despite the substantial social and health costs, the economic contraction during the pandemic was less severe than had initially been feared; and the recovery process was stronger. This was partly due to substantial macro policy support, the flexibility and responsiveness of the private sector, as well as the rapid development of effective vaccines.

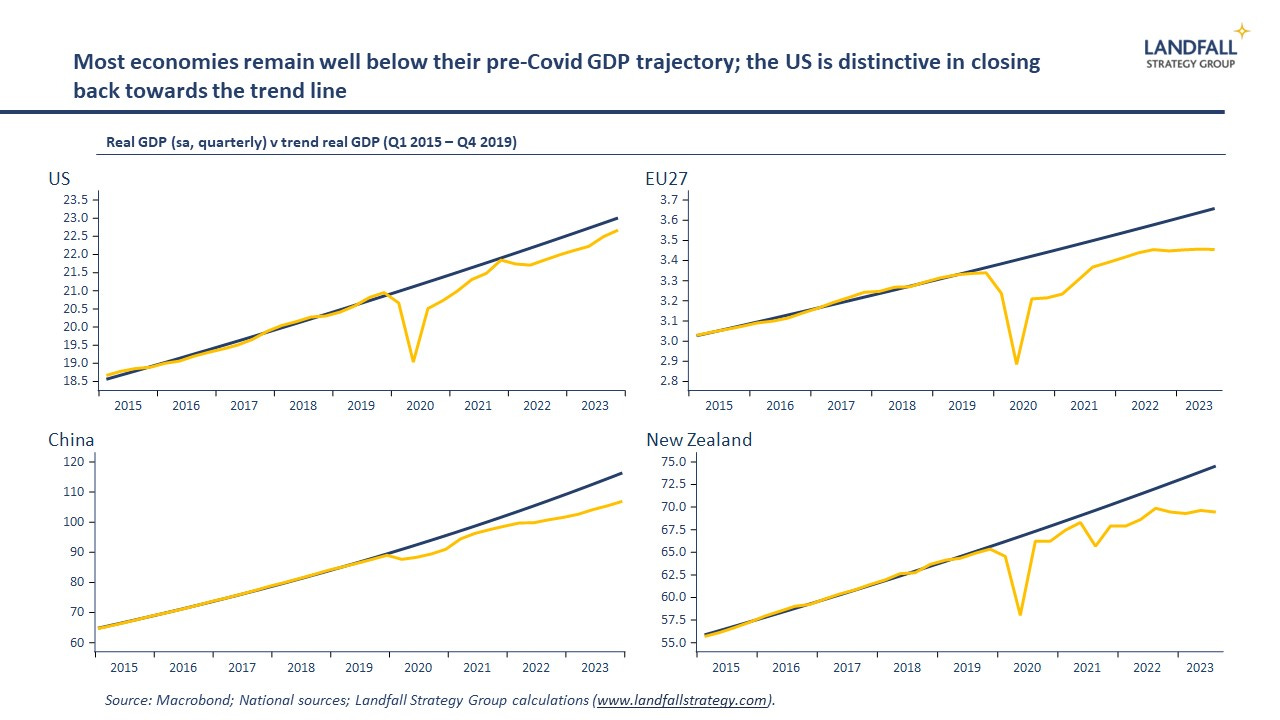

For the most part, the last wave of meaningful restrictions across advanced economies were lifted from early 2022, allowing for full reopening. China was the major laggard, lifting severe lockdown measures only at the end of 2022. Many advanced economies recovered quickly, returning to pre-Covid levels of GDP by the middle of 2021, although there is a gap left to pre-Covid GDP trend. Substantial GDP was permanently lost as a consequence of the pandemic, as well as the ongoing health costs.

Back to normal

Despite the rapid recovery, Covid also scrambled the global economy in many ways. The aftershocks from the pandemic caused the global economy to behave differently, from unexpected inflation dynamics to the expected US recession that never arrived.

The unexpected surge in inflation was partly due to macro stimulus, but also due to various Covid-related supply chain constraints and labour market issues. For example, labour markets tightened in many advanced economies on reduced migration inflows, reduced participation rates, as well as high quit rates as significant numbers of workers moved across the economy. This was reinforced by ‘labour hoarding’ by many firms.

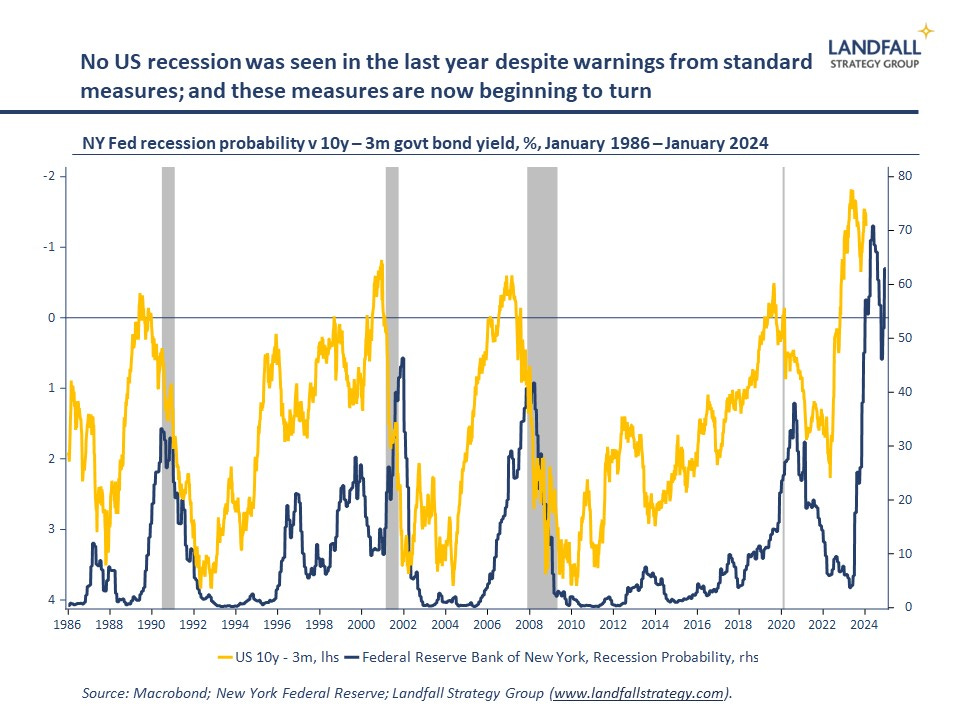

The estimates of the likelihood of recession in the US and elsewhere were well off. Standard predictors of a recession such as an inverted bond yield curve didn’t signal recession in the US, but rather a resilient economy: strong demand with supply side constraints, requiring higher interest rates before inflation faded, partly for transitory reasons. Indeed, data out on Thursday reported that US GDP growth was 3.1% in the year to Q4.

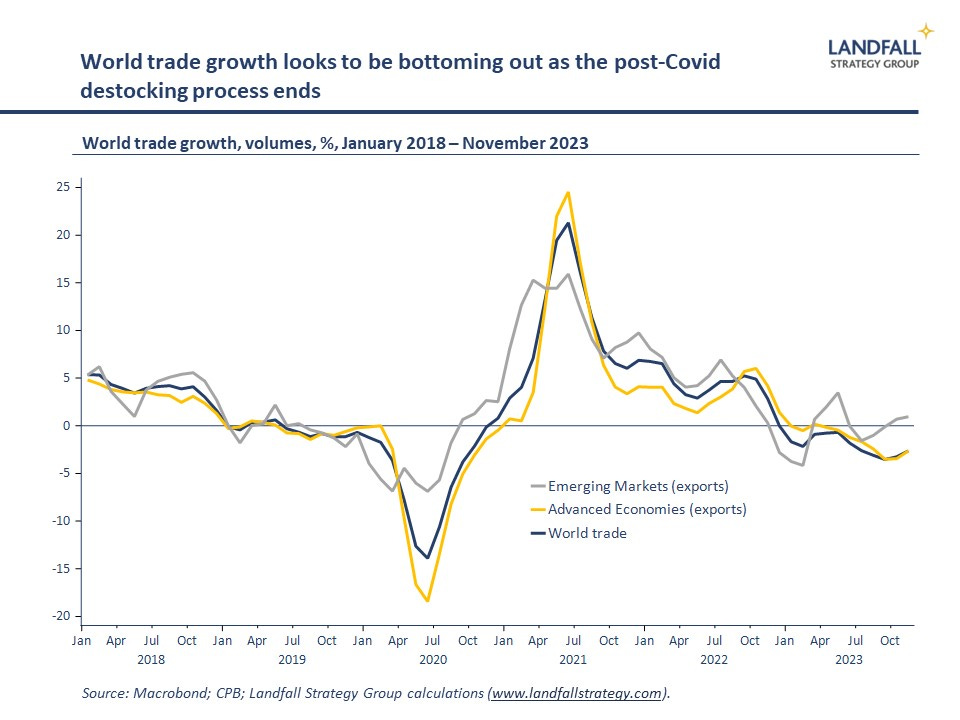

And similarly, there was strong growth in world trade flows from 2020 as demand for consumer durables exploded (relative to spending on services), reinforced by high levels of inventory-building as firms tried to strengthen resilience against supply chain shocks. But this led to excess inventories, and a process of de-stocking – during which world trade and industrial production was weak. But world trade growth looks now to have bottomed-up, with a better year ahead.

On many of these dimensions, the aftershocks of the pandemic are now fading. Global supply chain costs and disruptions have reduced sharply (although trade flows are now subject to other shocks, such as around the Suez Canal); labour market constraints have eased with migration at record levels around the world (and into advanced economies like New Zealand, Ireland, and the UK); and quit rates in many advanced economies are back to pre-Covid levels as the labour market reallocation process weakens.

2024 may be the first year in which the global economy is free from the aftershocks due to the pandemic and operates in a more normal manner. This will make it a bit easier to understand and interpret the global economy.

Structural change

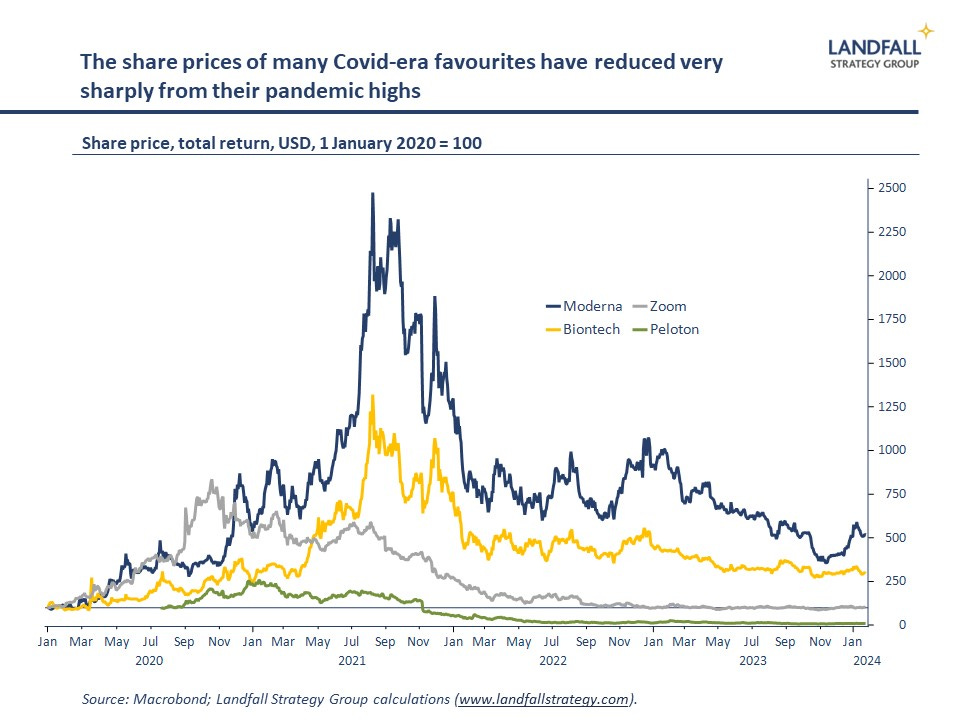

The ending of the Covid aftershocks will also make it easier to see the ways in which the pandemic has had a structural, enduring impact on the global economy. In some ways, the post-Covid world is familiar to the pre-Covid world: tourism has rebounded, particularly short-haul; the share of online commerce has settled back to its (rising) longer-term trend after spiking through the pandemic; and the share prices of Covid favourites from zoom to peloton have reduced sharply from their pandemic highs.

Even so, the post pandemic world is different in important ways. The pandemic has left an imprint. Along with changes in technology, geopolitics, and so on, these changes will require firms, investors, and governments to adapt. There are a few that stand out to me:

First, a changed model of globalisation. Globalisation functioned well during the pandemic, despite many challenges, and trade volumes have continued to grow since. But the Covid experience led to an increased focus on supply chain resilience, particularly in strategic goods from food and energy to medicines. Some of this was underway prior to the pandemic, as firms responded to over-stretched global supply chains, but this has been accelerated.

Governments have become much more focused on strategic autonomy. This inward turn has accelerated the process of global economic fragmentation, with greater emphasis on supply chain resilience and industrial policy in advanced economies.

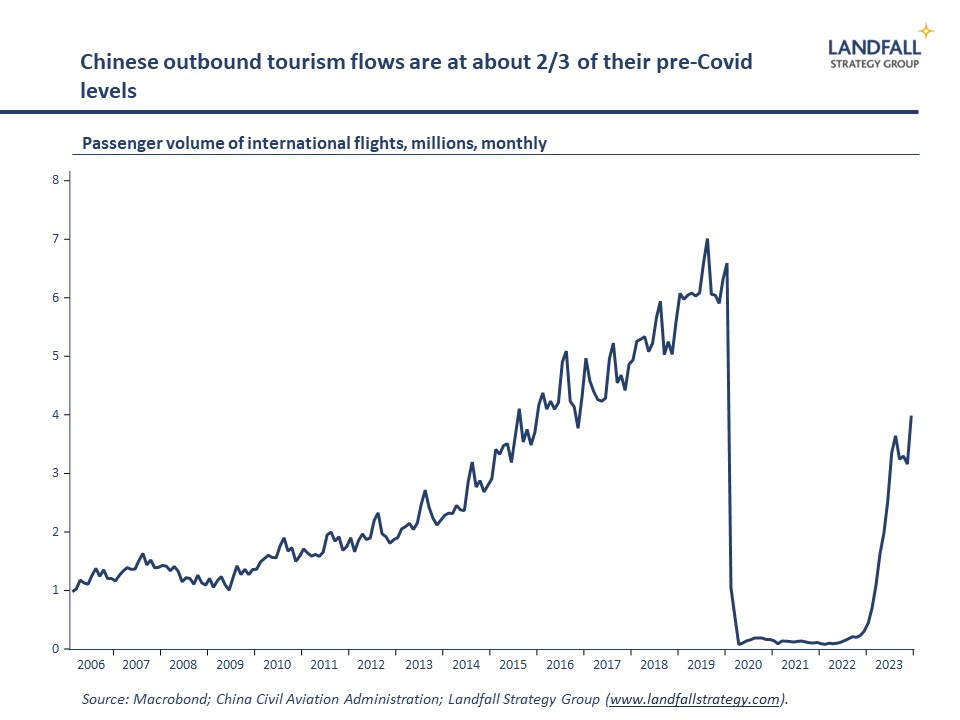

In China, for example, there is an increased focus on import substitution (‘dual circulation’); its imports/GDP ratio will continue to trend down. And China became a less open economy through the pandemic. The long closures of its borders led to effectively no flows of international tourists, migrants, and students through the pandemic. And these flows remain heavily constrained even after borders have been reopened.

Second, economic geography has shifted. People are working remotely to a much greater extent; days in the office for white collar workers average about 50% in major cities in the US and Europe. This shift to hybrid working looks sticky, despite ongoing efforts of some firms to require more days in the office. The evidence doesn’t suggest big productivity impacts one way or the other.

This has big implications for commercial real estate, the hospitality industry, public transport, and much else. The upward pressure on house prices across advanced economies – particularly outside major cities – is partly due to increased home working (as well as low interest rates); and the structural element of this increase is likely to persist.

Third, social and political preferences were shifted by the pandemic experience. Public attitudes on issues from the environment/green (more concern) and family (the birth rate decline has accelerated in multiple countries) to the role of government (more fiscal policy support) have shifted.

And concerningly, the decline in social and political trust has become more pronounced. Populism is not new (Trump, Brexit), but the lockdown measures took this to a new level (e.g. anti-government conspiracy theories). Populist parties, particularly in Europe, have been empowered by these dynamics – intersecting with concerns about the cost of living, migration, and so on. These new political realities will have an enduring effect on policy and governance.

The roaring 20s?

The aftermath of the Spanish Flu after WWI ushered in the roaring ‘20s of social and economic exuberance. There have been claims that Covid 19 might similarly lead to a roaring ‘20s. However, from an economic perspective, there is not yet much evidence of an upward shift in the growth trajectory; forecast GDP growth rates across advanced economies are generally lower than in the decade prior to the pandemic.

I will discuss productivity developments in a future note, but I still think that there is a plausible case that trend labour productivity growth will increase meaningfully over the next several years. This is partly due to the impact of new technologies, notably AI, but is also due to the investments made through the pandemic in digital, capex, new business models, and so on.

Although some of the distortions to economic behaviour from the pandemic are over, Covid casts a long shadow. The world is different, for good and for bad.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

24 Comments

And concerningly, the decline in social and political trust has become more pronounced. Populism is not new (Trump, Brexit), but the lockdown measures took this to a new level (e.g. anti-government conspiracy theories). Populist parties, particularly in Europe, have been empowered by these dynamics...

So let me get this straight...the majority of a country's population voting for the parties and policies they prefer (something that used to be called "democracy") is now called "populism", which is bad?

What policies? All I have heard is repealing everything the bad lockdown worst government ever implemented and life will return to rosy?

Thats a start...

Not all information out there is factual and/or correct. If certain of the population only think they know what the problem is from what they've heard or seen written about an issue i.e. readily believe that which they hear/read without reflection/giving any depth of thought to, then perhaps democracy has been corrupted. Education, which supposedly gives rise to critical thinking skills, underpins democracy?

“Some ideas are so stupid that only intellectuals believe them.” Orwell

Many would argue that modern education focuses more on critical race theory than critical thinking skills.

An element of truth in both responses ...... added to the mix vested corporate interest and the power of money opening the door to political access and influence.

So let me get this straight...the majority of a country's population voting for the parties and policies they prefer (something that used to be called "democracy") is now called "populism", which is bad?

I recommend reading the work of Thomas Frank if you're interested in populism. Reality is that populism has been around for a long time - the New Deal was a result of populism. Closer to home, so was the rise of Cindy Ardern.

In his latest work, The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, journalist Thomas Frank takes on such a challenge to rescue the terms “populism” and “populist” from the mouths of those he deems unfit to use them: the anti-populists. Part history, part polemic, the book argues that both terms have been warped by capable interpreters: his fellow critics of American history and culture. In short, Frank seeks linguistic rectification even if it means becoming that which he abhors with a smoldering passion: a cultural snob.

By seeing the ways in which anti-populists have historically misused “populism” and “populist” at different moments in American history, Frank wants us to better understand how pessimism about popular democratic participation has enlivened “the paranoid right.” He begins his analysis by laying out the historical foundations of populism and exploring the 19th-century “Pops” (rhetorical shorthand for the Kansas-based agrarians who challenged the economic elites of the time). The first chapter is his descriptive baseline: the definition of populism that grounds his reclamation project for the book as a whole. “Populists both loved knowledge and rejected professional elites. The reason was because the economic establishment of that age of crisis was overwhelmingly concerned with serving business, not the people.”

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/reclaiming-populism-on-thomas-frank…

The media now reports anything right of dead center as “far right”. It has completely lost objectivity and credibility

Example?

The non-action of the police in removing protesters trying to prevent a fishing competition because they have some 'issue' with the government. Really this scum should have been dealt with by the police in riot gear, but that would have been divisive and racist and 'far right' (even though the tribe they were affiliated with said they did not support there actions). Meanwhile the police stand by and no nothing. So, situation normal. We have scumbags breaking the law, police standing by doing nothing, any mention of it is 'far-right' and the fishers just go somewhere else and continue their competition ignoring said scumbags. So the point is, the media gives this type of scum oxygen, as if they have some right to disrupt everyone because they don't agree with 'whatever'. The story should have been about the police roughing them up and throwing them in the slammer, not some sob story about some illiterate twits trying to stop a fishing competition, but that is what we got.

Just as well you missed the groundswill protests Jezza - the projected entitlement and disruption caused would have tipped you over the edge.

I saw one of those go by. They were quite different, and you know it

There were a lot more Jeremy's in that protest?

Well said. Totally agree with your comments. Time true New Zealanders stood up and be counted

Reply to "History Repeats"

A very astute observation on your part.

Language is the main tool of propagandists.

David Shilling's "Project Syndicate" contributions are very much about introducing the reader to new vocabulary designed to shape and influence the readers perceptions to favour globalist themes.

His bio on the website of the World Economic Forum is typical of many like him, cultivated to have access to government at high levels mainly with the support of the W.E.F itself.

The key is to understand where these ideas are hatched, whose driving them and for whose interests and purpose.

Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen Real median wages stagnated over decades. They grew only 8 percent between 1979 and 2019. At the age of 30, 90 percent of my generation were earning more than their parents at the same age. In contrast, only half of children born in the mid-1980s earned more. Incomes became more volatile, especially for people without college degrees. It became harder to buy a home; harder to rent one. Harder to pay for healthcare; harder to pay for education. In 2011, parents worked two to five additional hours per week compared to the parents of 1965. And to buy what they needed, middle-class Americans borrowed, adding to significant mortgage debt and student debt.

This was the middle-class reality when, suddenly, middle-class Americans were hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Michael Hudson Well, we’ve discussed in the past how it happened. The United States, starting with President Clinton and actually with President Carter, decided to help American firms make higher profits by moving their labor force out of the United States, by trying to shift manufacturing first to Mexico, along the maquiladoras under Carter, and then under Clinton to China and Asia.

And the idea was to create increasing industrial unemployment in the United States to prevent labor’s wages from rising. And the theory that has guided the Democratic Party’s economists is, if you can cut wages, there will be higher profits and higher profits will lead to more prosperity.

Well, the reality is that you cut wages by moving your industry outside of the country, by de-industrializing. And that is still the policy that America has taken. And it has replaced industrialization with financialization to make money financially, hoping that the companies that have now moved out towards China and Asia and other countries are going to be able to have higher profits and essentially become more prosperous for the donor class to the Democratic and also the Republican parties.

US: ALERT: The 15 Year Silent Depression

NZ: 1) real GDP per capita since just prior to Covid (Dec 2019) 2) % falls in real GDP per capita in multi-quarter downturns in recent decades Link

Boeing’s nosedive: How greed ruined a great American company

The Nationalization of Boeing Begins

The Senate is likely to hold hearings, with Boeing CEO David Calhoun, who is trained as an accountant, roaming Capitol Hill to answer questions.

Things are getting back to normal, despite the best efforts of Labour, maoris and Comrade Ardern.

Normal. A government that governs in the interests of the top 10% of the wealthy of New Zealand. If this is what you want for New Zealand go for it but it is not a New Zealand that I want.

The NZ you want encourages apartheid in NZ, wants to gouge so-called 'rich' people with a wealth tax, the ones who work hard and take risks, destroy the farming industry because of 'global warming', throttle the tourism and airline industries because of 'emissions', squander billions on moronic boondoggles like the dopey gun buyback, the harbour bridge cycleway, 3 Waters, the light rail fail, handouts to maoris, Pike River and 14,000 more civil servants.

NZ was headed for economic ruin, and the electorate knew it.

In the 1980's Corporal Muldoon in his wisdom decided to gouge so-called 'rich' kiwis 66% marginal tax rate, something he called, the 'temporary tax surcharge'. This spawned a plethora of tax avoidance schemes and even blatant tax evasion. Everything was done with cash. The Premier of QLD, Joh Bjelke-Petersen sent a message to kiwis promising better weather, lower taxes and no death duties.. Thousands took the bait, emigrated to Aussie with their skills and money never to return.

Both my children have emigrated to Australia with their skills and I've strongly suggested they don't come back.

Political parties like staying in power and they do that through building their voter base.

Labour builds their voter base by making more people poor and dependent on the state whereas National builds their voter base by lifting people out of poverty and therefore are more likely to vote National.

In other news

"Hong Kong court orders China Evergrande to liquidate with debts of US$300 billion"

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/business/china-evergrande-liquidation-h…

The author's bio from the website of the WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM.

[He is a globalist helping to form your opinions and ideas and has access to the highest levels of government]

Dr David SkDrilling is the founding Director of Landfall Strategy Group, an economic and policy advisory firm based in the Netherlands and Singapore. David advises governments, companies, and financial institutions in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe on the impact of global macro, globalisation, and geopolitics. David writes regularly on global economic and political issues [for Project Syndicate].

He has recently served as a Senior Advisor to the McKinsey Centre for Government; as Senior Advisor to the Secretary of Foreign Affairs & Trade in New Zealand; and as a Fellow at Singapore’s Civil Service College. Previously, David was an Associate Principal with McKinsey & Company in Singapore, as well as being a Senior Fellow with the McKinsey Global Institute. Prior to joining McKinsey at the start of 2009, David was the founding Chief Executive of the New Zealand Institute, a privately funded, non-partisan think-tank. Until 2003, he was a Principal Advisor at the New Zealand Treasury, where he worked primarily on economic growth issues. David has a PhD in Public Policy and a Master's in Public Policy from Harvard University, as well as a Master's of Commerce (Hons) in Economics from the University of Auckland.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.