By David Skilling*

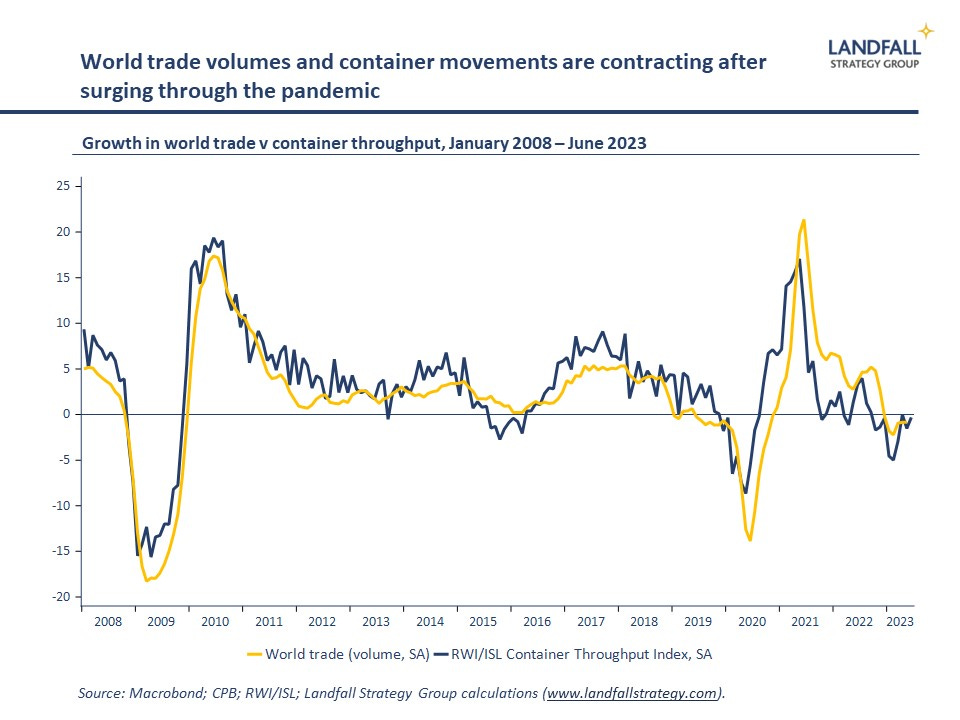

A few recent developments highlight some of the challenges facing global trade flows. Last week, Danish shipping and logistics giant AP Møller-Maersk reported revenues 40% lower than last year, with profits down ~70%, on weaker shipping volumes and prices.

Maersk forecast that global container demand would contract by 1% to 4% this year, marking down its previous forecast on reducing inventories and weaker consumer demand. Maersk’s performance is a useful barometer of the strength of global flows; shipping container movements are a good proxy for world trade. Maersk’s share price is down by about one third from its pandemic highs, although it remains well above its pre-Covid levels.

Alongside this muted outlook, China’s export and import growth data on Wednesday were worse than expected. Chinese exports shrank by 14.5% in the year to July; and imports contracted by 12.4%, reflecting an anaemic Chinese economic recovery. China is not alone: export growth across many exporting powerhouses in Asia (Singapore, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea) has also moved into negative territory, broadly in line with China.

This weakness is reflected in China’s inflation data, out this week. China’s PPI inflation (discussed recently here) continues to decline, to -4.4% in the year to July. And headline CPI inflation moved into negative territory at -0.3% in the year to July. China is now exporting deflationary pressure to the world.

Other measures of global flows reflect a similar story. Last week’s CPB world trade index (data to May) shows a weakening of world trade volumes, particularly from advanced economies. As the world’s largest exporter, China’s weakening export growth will weigh on this index over the coming months. And last week’s release of the global supply chain pressure index shows ongoing easing after surging through the pandemic, as international container shipping prices reduce and port delays and congestion ease.

Explaining slowing global trade

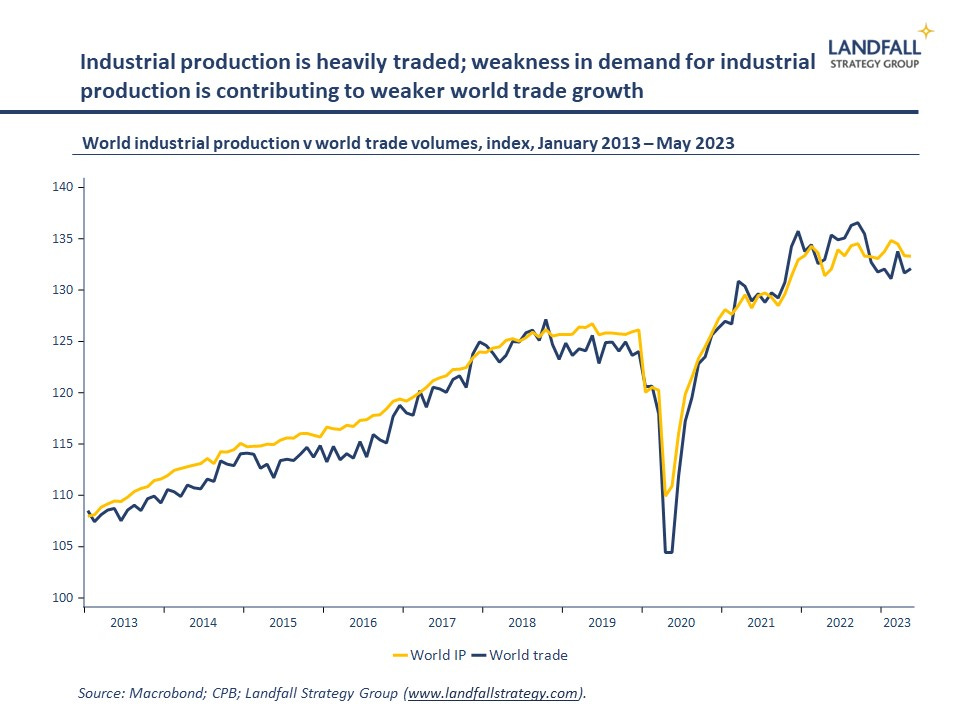

Many of these global trade dynamics are cyclical in nature, reflecting a slowing global economy. And there is a post-Covid normalisation process underway in world trade after strong performance through the pandemic, partly due to surging demand for durables. An industrial recession has emerged as patterns of consumer demand normalise after the pandemic, leading to reduced (heavily traded) industrial production.

There will be some mean reversion in world trade growth, with the WTO and others picking better rates of world trade growth from 2024. Against this, trade and investment sanctions – and inwardly-focused industrial policy (from the Inflation Reduction Act in the US to China’s various localisation initiatives) will likely drag on world trade growth – although these are not yet enormously material.

Weaker export growth is also partly due to weaker export prices, with some resilience in trade volumes. China’s export prices were down 7% in the year to July, the weakest reading since 2009, partly in response to weaker demand. And CPB report declining world trade prices. The surge in inflation flattered world trade growth over the past few years, and deflationary dynamics are now weighing on export values.

China is exposed to these dynamics. For example, China accounts for ~30% of global industrial production – and so a slowdown in demand for industrial goods will affect it. However, China is generating strong export growth in some areas, such as motor vehicles. China has recently overtaken Japan to become the world’s largest car producer, largely because of its dominant position in electric vehicles.

And there are some additional forces at work that will weigh on China’s export performance over time. China is a higher cost location than it was, and some firms are relocating production to other economies to access lower cost production – or closer to end consumers to reduce supply chain risk.

Investment in export-oriented production into locations from Vietnam to Mexico has increased strongly as firms diversify out of China. This reduces exports from China, even if in some cases, it is Chinese firms exporting from these locations.

Friend-shoring with Chinese characteristics

Geopolitics is also a factor. The increased intensity of sanctions as well as the preference among many Western firms to reduce exposure to China is leading firms to diversify away from China as a production base for exports. These risks will likely to intensity as big power rivalry continues to escalate. The announcements this week from the Biden Administration on investment restrictions to China are the latest example. The incentives for relocation are reinforced by the increasingly challenging domestic business environment in China.

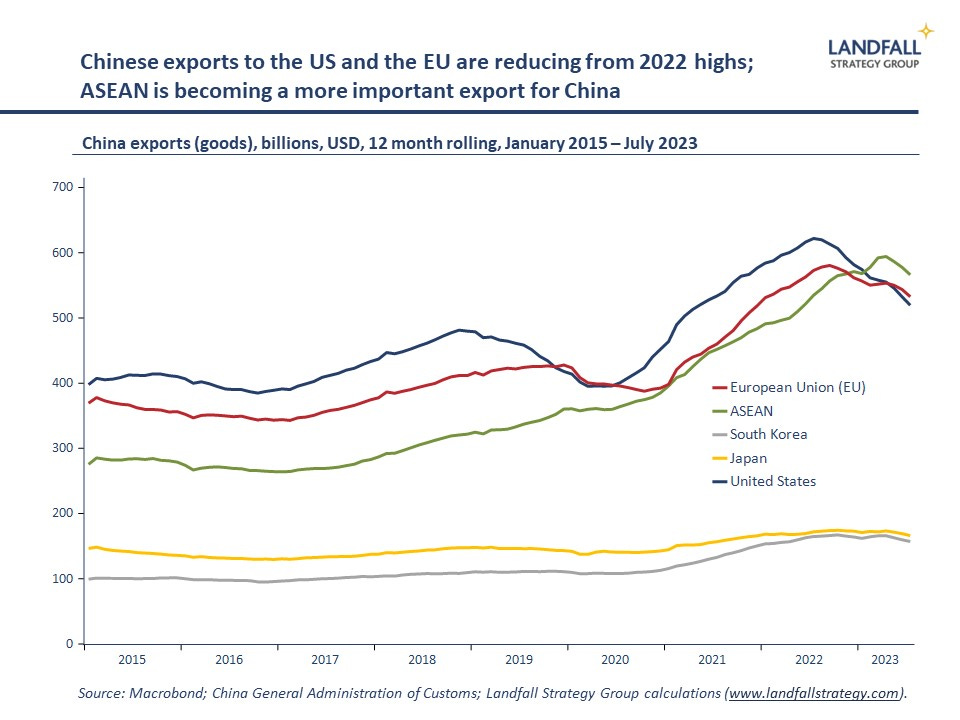

At the moment, however, the impact of geopolitics on China’s trade flows can be seen more in the composition of exports and imports than in China’s aggregate trade growth rates. I have noted previously that China’s imports are increasingly rotating towards friendly countries.

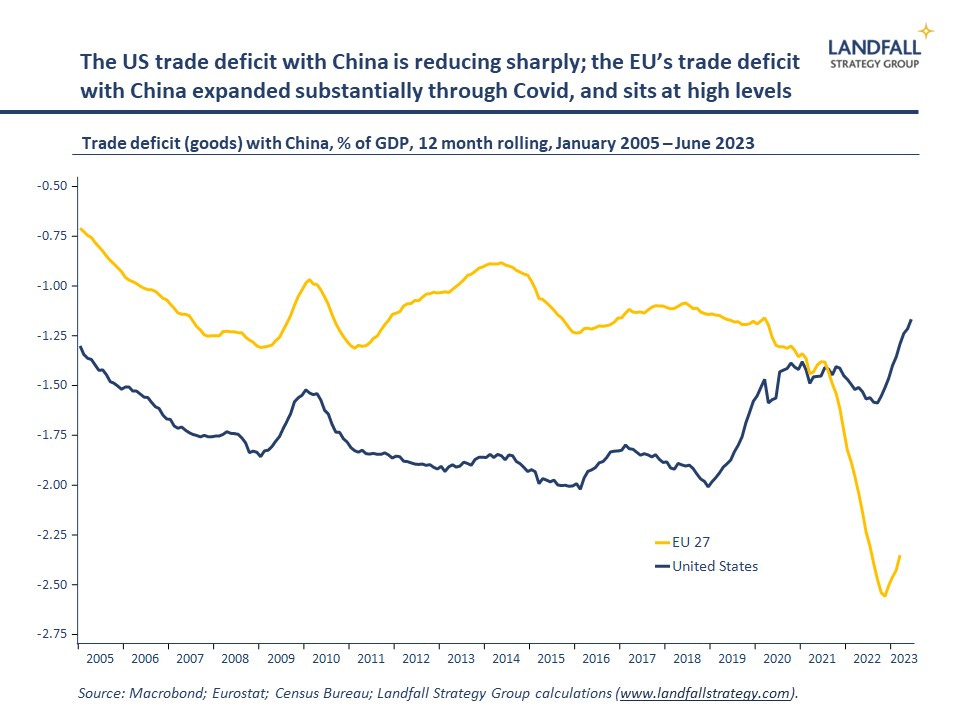

And China’s export growth is stronger with friends than with geopolitical rivals or countries with whom there are political frictions. Exports to the US, Japan, and others are down by more than to ASEAN, the GCC, and others. Indeed, the US trade deficit with China has been shrinking on reduced imports of Chinese goods over the past few years.

One partial exception is Europe: China’s exports to the EU have reduced but it accounts for a higher share of China’s exports. Indeed, EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis this week described the EU’s trade deficit with China as ‘staggering’ – and blamed China’s restrictions on European imports. However, a key part of the story is also Europe’s reliance on China for the green transition.

The EU’s large trade deficit with China (~2.3% of GDP, compared to ~1.2% for the US) has geopolitical implications, reducing the EU’s ability and willingness to de-risk from China. Indeed, the EU noted on Thursday that it won’t yet sign onto the new US restrictions on investment in China’s technology sector.

Looking forward – and small economies

Overall, global trade flows are slowing for both cyclical and structural reasons. But this is not deglobalisation; the evidence suggests more of a reshaping of global flows – more regional and more political. And as discussed recently, greenfields FDI flows rose strongly last year and other forms of trade are growing strongly, e.g. digitally-delivered commercial services.

Globalisation is not ending, but it is clearly changing. National and company growth models will need to change in response. But, particularly for smaller economies, externally-oriented growth models will remain an imperative: international activity is the productivity growth engine of small economies. Although it will be a more challenging environment, small economies can continue to prosper.

Indeed, small advanced economy export growth continues to run slightly ahead of other advanced economies. This is supporting stronger overall GDP growth performance across the small advanced economy group relative to larger economies. And my constructed portfolio of large cap global firms from small economies continues to perform well relative to major indexes.

Given the deep exposure of smaller economies to global dynamics (and lower margin for error), they need to adjust growth models and economic structures to position for this new world. Larger economies, from Germany to the UK, are struggling to pull off this transition to new competitive and geopolitical realities. Small, globally exposed economies, will need to do better.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

If you have not already, you can subscribe for free to receive occasional public notes - or take out a paid subscription for full access to these notes:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

4 Comments

"China is now exporting deflationary pressure to the world."

When the worlds factory is exporting deflation where does your credit growth come from?

Who cares. Sell your bank shares and you'll not care either. ;-)

I don't expect China to continue to be the huge exporter of high labour input manufactured goods it has been, they just don't have the demography for it. The countries demographics mean it's more likely to be a leader in old age homes and assisted living.

Curses, means we'll have to compete with them for nurses.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.