By Lixin Jiang*

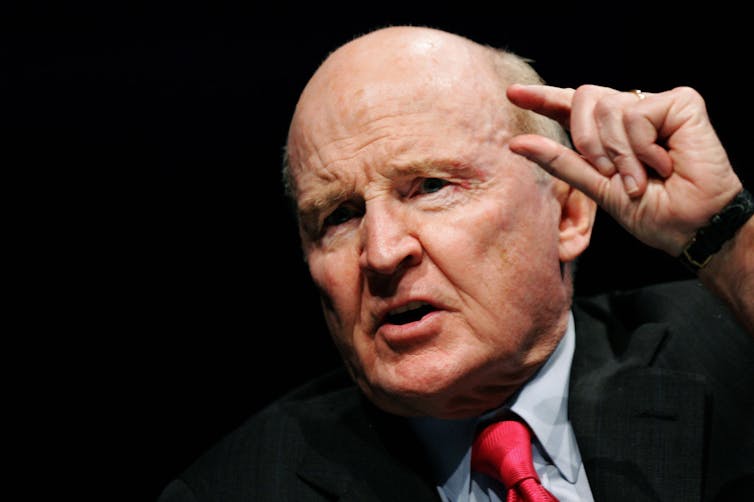

Former General Electric chief executive Jack Welch famously promoted the “20-70-10” system to increase labour productivity. Managers were asked to rank employees on a bell curve; the top 20% received rewards, while the bottom 10% were fired.

Yahoo, Amazon and IBM, among many others, later adopted this performance review approach, termed stack ranking, forced ranking or “rank-and-yank”. Similar practices – termed “up or out” – dominate law firms, accounting firms, the military and professional sports teams.

The goal of “rank-and-yank” is to stimulate subordinates’ work performance by creating the constant threat of job insecurity. It’s a fairly ruthless way to improve the bottom line, but some employers might find it justifiable if it worked. So does it?

Our research reveals the answer depends on the level of job insecurity and the performance criteria in question. But the overall answer might not please fans of the late Jack Welch.

Insecurity and performance outcomes

Researchers disagree about the effects of job insecurity on work performance. Some focus on the adverse consequences of job insecurity, while others spotlight its potential motivating function.

Researchers at the University of Auckland and the University of Texas at San Antonio theorised that the impacts of job insecurity depended on its level of severity and the specific types of work performance that were considered.

Given no single empirical study can adequately address this question, the best way to understand it is to conduct a meta-analysis.

Based on data from over a hundred studies into “rank-and-yank” we concluded that Welch was both right and wrong.

Insecurity as motivation?

We observed that when job insecurity is extremely high, employees do increase their performance and the types of behaviours that are explicitly recognised by the formal reward system.

Similarly, employees also take on tasks that are beyond their formal duties but are beneficial to organisational productivity and visible to mangers. Such tasks may include attending non-required meetings, sharing informed opinions to solve work problems, and volunteering for overtime work when needed.

This appears to be good news. But such “motivating” effects of job insecurity are very weak (albeit statistically significant), with very few practical implications in the real world.

Thus, the job insecurity associated with a “20-70-10” approach is less of a motivating factor for workers than Welch might have hoped for. Additionally, as job insecurity increases, employee creativity declines – and then flattens out.

Employees’ creativity, or their ability to generate innovative and practical ideas or solutions, can contribute to an organisation’s success and is therefore highly valued by organisations.

Moreover, employees facing low to moderate levels of job insecurity decrease behaviours that may benefit their colleagues, such as lending a hand when needed.

Taken together, extremely high job insecurity does not contribute to employee creative performance or “good citizenship” in the workplace.

An unsafe work environment

The data also revealed a link between job insecurity and a decline in employee safety performance.

Safety performance includes wearing safety gear, following safety protocols and communicating safety concerns to managers. These measures are critical to prevent employee injuries and on-site accidents.

20 years later, a fascinating reevaluation of Jack Welch's tenure as #CEO of @generalelectric describes a trail of destructive practices ("rank & yank") and distrust, & labels him as "the man who broke capitalism" @dgelleshttps://t.co/BfSs9iiGfI pic.twitter.com/hgkSrnCNML

— Julian Barling (@JulianBarling) June 2, 2022

Job insecurity also consistently increases the likelihood that employees engage in destructive behaviours that harm the organisation, including calling in sick when not ill and destroying or stealing company property.

Overall, considering the overwhelmingly negative effects of job insecurity on employee attitudes, organisational commitment, health and wellbeing, the small, positive, motivating effect of increasing job insecurity may not be worth it.

Uncertainty and productivity

Considering New Zealand’s poor productivity output, it is worth managers considering how they can effectively motivate workers.

According to the Productivity Commission, New Zealanders worked 34.2 hours per week and produced NZ$68 of output per hour. Yet in other OECD countries, employees worked 31.9 hours per week and produced $85 of output per hour.

So, finding ways to increase employee performance is important. But, considering the data, using a “stick” of job insecurity is unlikely to achieve it.

With the threat of job loss, employees are likely to engage in “quiet quitting”. Employees will also refuse to go the extra mile and instead are more likely to only do the minimum required.

Considering the current low unemployment rate (below 5%) and the “great resignation” trend that emerged after COVID-19, employers need to think twice before using job insecurity as a motivator. People may simply find an alternative employer that treats them with a “carrot”.

Retaining talent and increasing productivity requires offering employees better wages, opportunities for training and career advancement, greater control over their work, and more decision-making opportunities.

Essentially, employers should treat employees the way they want to be treated themselves. After all, as studies have shown, a happy employee is a productive employee.![]()

*Lixin Jiang, Senior Lecturer, University of Auckland. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

25 Comments

I believe a nickname was Neutron Jack. Get rid of people and leave the building standing, the main effect of a neutron bomb.

... around the same era was another executive called Al " chainsaw Al " Dunlap .... similar methodology to Jack Welch ... snip , rip & bust ... boot people out enmasse , walk away with a bag of money for gutting the staff ...

Yet another academic who doesn't factor in energy.

Imagine if you expected every study about every subject to cross reference your pet interests.

Everything's physics in the end. Or maths, if you ask the mathematician.

Boring.

Depends on the environment, the industry, and stage in the economic cycle. Welch came to prominence in the down cycle of the 80s.

Having operated in a few markets, it certainly does seem like a lack of competition and a surplus of security leads to more subdued performance. If there's no one else to call, there's less reason to hustle.

Exhibit A: local & central Government.

My employer adopted this approach a few years ago. So many mid-level managers got the boot...

But has it made your workplace a better place?

So many mid-level managers got the boot...

I've also worked as a manager under a "forced ranking" system for a few years in a multinational private sector company. One of HR's tools to kill "people & culture" stone dead in as short a time as possible. Gave new meaning to "JOB = Just Obey Boss" ensuring dysfunctional groupthink & zero creativity. Lasted about 5 years at my level till the HR fad of the year changed with their staff rotation. I lasted over 25 years there myself; operations staff learned to roll with these "ideological burps" & eventually undermine them with our subtle ways & means.

There are few things worse in business than HR fads.

Ain't that the truth!

If going over and above is so important suddenly, then pay people for it and make that the new normal in terms of expectation.

Otherwise it's just "Be more productive by generating revenue without being paid for it" and I kind of feel like people are waking up to how much of a crappy deal that is.

Usually markets reward value. You have to have an exceptional amount of leverage otherwise.

Lets have more holidays, that will increase productivity.

... we're all in the top 20 % where I work ... all 100 % of us ... it's such a struggle to retain staff , even with a good hourly rate , the boss & foreman look so elated each day when we turn up ...

Easy to take a bit out of history, without any context of the time, & write an article. It currently forms the basis of our warped & woeful educational system & this article fits right in. Without the context of the times (in this article's particular case, with many cases over many times) then the article is just more noisy academic speak, which tends to dominate our media these days. There was a good reason for neo-liberalism in the 80's, in that it followed the worst decade of existence (the stoned 70's) where nobody did anything as they were still on their way home from Woodstock. It's fine to throw stones at the 80's & the 3 decades that followed but if you can remember back that far you will learn that what we had before that was absolute chaos. Indeed, from what I saw & remember, it was was the biggest withdrawal from recreational activities in human history. And this includes the absolute debacle that was Vietnam, along with NZ's own version of a socialist megalomaniac in the form of Muldoon. The 80's happened for a very good reason. We were dead on our feet before that.

Not everyone had the same experience in the 1970s. There was lots of opportunity for those of us who watched all the others "turn on, tune in, drop out". I left school to start full time work as a laboratory technician in 1972 age 16 (with UE). By the end of the decade I'd stayed employed & been promoted to factory manager, got married, had 2 kids, bought a house...

Wrong john,

No, there wasn't a good reason for neo-liberalism then or any other time, though I have to admire the tenacity with which its proponents-the members of the Mont Pelerin Society pursued their aims for decades. I refer to such as Hayek and Friedman. Reagan's election team had over 20 members in it.

Tax cuts to multi-nationals? Like Ireland? Productivity to the moon! ! !

I don't think it would work in my industry. If people felt insecure in their jobs, they'd just look for a more secure job elsewhere.

Yeah - i think this only works for ego-centric, psycho bosses in yesterdays markets.

Productivity is a top down thging... iut comes primarily from awesome leadership (and not the sort of nonsense our politicians and NZ CEO exhibit in the main) where people leave only if they are embarrassed they didnt put in the same effort as the ceo, the bosses rest of the team to achieve their personal, team and business goals. Where leaders lead by example and admit mistakes and try new stuff. It comes from the culture where people WANT change in the organisation as they can see the leaders embrace it and they need to to help the whole company progress. None of this 'she be right' nonsense that prefers the status quo.

NZ also has this pointless tall poppy thing where employees dont want to outperform their peers lest they get ostracized. It needs to sort that out somehow as its mega embarrassing for the country. Outliers who work hard and do well should be celebrated and rewarded and others encouraged to want to achieve the same.

Similarly failure in NZ is looked down on. Most people give uo trying new stuff at all ages coz they get embarrassed to fail. Deal with - you cant enact change without dropping a few clangers whilst experimenting with ideas.

Again - it all comes from the leader and the culture they create. In NZ we unfortunately dont have enough good leaders, and need to change the general culture.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.