This is the Executive Summary of a Report prepared by Sense Partners for the New Zealand China Council, updating where the New Zealand-China trade relations has moved to.

The New Zealand-China trade relationship is mutually beneficial and has played a significant role in pulling New Zealand through the economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While services trade has been impacted by the slowdown in tourism and educations flows, goods exports to China have grown during this time. Exports to other markets have slowed, further elevating discussions around New Zealand’s market concentration risks.

The New Zealand China Council (NZCC) has engaged Sense Partners to:

- Provide an update on New Zealand’s trade and investment relationship with China.

- Examine how the relationship has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Consider the risks and mitigating factors for New Zealand exporters of increased market concentration in China.

This report updates and builds on a previous report by Sense Partners for the NZCC, “How many eggs, in how many baskets?”

Key findings

- The bilateral trade relationship amounted to $37.70 billion of goods and services in 2021, up from $31.30 billion in 2020 and $33.41 billion in 2019.

- New Zealand exported $21.45 billion of goods and services to China in 2021 and imported $16.26 billion.

China has played an important role in pulling New Zealand through the COVID-19 economic downturn…

- In 2021, New Zealand’s total goods exports rose by $3.4 billion (5.4%) from 2020. This is despite exports to markets such as Australia and the UK falling.

- Our goods exports to China grew by $3.3 billion (19.8%) over 2021, as the Chinese economy rebounded relatively strongly from its initial COVID-related output declines.

- New Zealand’s goods imports from China also grew strongly over 2021, increasing by $3.1 billion (26%) from the previous year.

- Export growth to China has resumed its strong trend after a very small drop in 2020 ($100 million, or 0.6%). The 2021 growth rate of 19.8% is similar to pre-COVID growth of 23.3% in 2019 and 21.8% in 2018.

- It seems reasonable to suggest that China has played an important role in mitigating the disruption caused by COVID on the New Zealand economy.

…which has pushed up our export concentration for goods to 32.6%

- In 2021, China accounted for 32.6% of our goods exports, up from 25% in 2018. Our next largest export partner, Australia, accounted for 11.5%.

- Our share of exports to China has grown faster than that of many other developed countries over the past decade, from 12.8% in the year to 2011 to 32.6% now.

Bilateral services trade has been hammered as tourism and education flows ground to a halt

- The pandemic has seen our exports of tourism services to China fall by over $1 billion, (68%) in 2020, with a further $390 million fall in 2021.

- Education exports dropped by ‘only’ $250 million or 19% in 2020, reflecting the fact that there is an existing group of Chinese students in New Zealand that have stayed since the pandemic began. Education exports rose slightly in 2021 but will not recover until borders open fully and students are confident travelling overseas to study again.

- While there has been strong growth in sectors such as Insurance and pension services and cultural and recreational services in the past year, these are very small in comparison to education and tourism. No data is available on digital trade.

- Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has not resulted in a structural change to New Zealand’s goods and non-travel services trade with China.

Being concentrated on one key market is not unique to New Zealand

- New Zealand’s overall export concentration of 32.6% to China is lower than that of APEC members Chinese Taipei (50.1%), Australia (40.3%) and Chile (39.8%).

- Many economies have certain products for which China takes more than half of their total exports, such as metal ores (e.g. India, Indonesia, Colombia, Mexico, South Korea) and wood pulp, paper and paperboard (e.g. Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand).

- In 2020, other developed economies sent a much greater share of their exports to their main trading partner (albeit they are geographically much closer than New Zealand is to China):

- Canada sent 72.1% of its exports to the US.

- The UK sent around half of its exports to the EU.

- Both Canada (in the Trump administration period) and the UK (post-Brexit) provide examples that the risks of export concentration are not limited to China.

Trade disruptions come in many forms

- Many events can disrupt global and bilateral trade patterns, including income slowdowns, fuel price shocks, pandemics, economic coercion, sanctions regimes and conflicts. As a small, open economy, New Zealand is highly exposed to these shocks.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of global trade to sudden shocks. The impact of that sudden shock is giving way to more gradual shocks in the form of constrained supply chains, global inflation and an uncertain global recovery.

- Other more gradual shocks include increased domestic production within China, an objective of its “dual circulation” strategy. The initial impact may be on strategic goods, such as semiconductors, but it is possible that the range of goods considered strategic by China could potentially become broader in due course.

- Trade disruption between Australia and China, driven by foreign policy disagreements, has loomed large in the past 18 months. Recent research3 indicates that – in aggregate – the impacts of Chinese trade policy on the Australian economy have been relatively moderate to date, although specific sectors have felt the pain more keenly (e.g., timber, wine).

- In part this is because affected Australian exporters have redirected exports away from China towards alternative markets: the exports that were destined for China are not simply lost.

- With this in mind, we have carried out some indicative scenario analysis to explore the potential impacts of disruption in our trade with China.

- This is not an exercise in forecasting or a prediction of what will happen. It is designed to provide some perspective on the risks to our export sector from being highly exposed. A formal model of global trade would provide more nuanced estimates.

We need to consider competing suppliers to China as well as our export concentration

- A product is a priori most exposed to trade disruption when:

- New Zealand sends a large share of total exports of that product to China (we are highly exposed); and

- China has many other large import sources for that product to which it could switch (we have a low market share in China, and hence low leverage).

- Many other factors also determine exposure. They include consumer preferences, the quality of the good, whether the product is essential or a luxury good, where it fits into value chains, and the ability of other producers to scale up to meet supply gaps. For this simple analysis, we focus only on export and import shares.

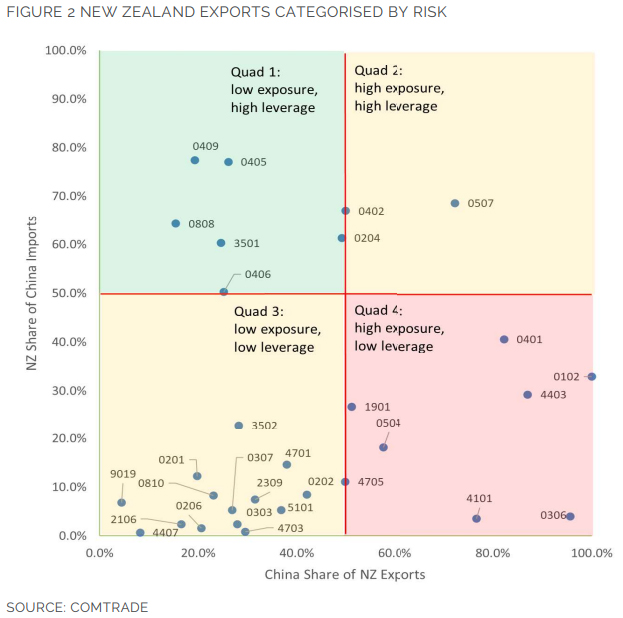

- Using an arbitrary threshold of 50% for exposure and leverage, we can divide up our key export products into risk quadrants, as shown overleaf.

- The products in Quadrant 4 are, prima facie, the most exposed into the China market. For example, China takes 97% of New Zealand’s total exports of lobsters and crabs (HS0306), but it sources about 95% of its total imports of these products from markets other than New Zealand.

- The other products in this high-risk quadrant are live cattle (0102), logs (4403), milk and cream (0401), infant formula (1901), raw hides (4101), wood pulp (4705) and green offal (0504).

- Each product has its own context. For example:

- Live cattle exports from New Zealand will be banned from 2023.

- Green offal was previously a waste product until a market was found in China, though uses are increasing elsewhere.

- And as we have seen through COVID-19, the New Zealand dairy industry, including for milk, cream and infant formula, does have the ability to pivot in its product mix. This enables production to be shifted between types of dairy products and/or channels, mitigating the impact of trade disruption.

The redirection of exports from China to other existing markets would mitigate much of the economic cost of trade disruption

- We built a simple scenario model to illustrate how exports of the products listed above could be redirected to alternative markets in the event of a one-year disruption to imports from New Zealand, and the impact of such a disruption on New Zealand’s export revenue.

- We assume 10% of those exports cannot be redirected and the remaining 90% is spread across existing markets based on their share of current non-China exports. Prices in these alternative markets decline, with a price elasticity of demand of -0.2.

- As noted above, each product has its own context. Some sectors, like dairy, can shift between different types of product. As a result, the amount of dairy products which cannot be redirected is likely to be significantly less than 10%.

- Table 1 summarises the potential impacts on total New Zealand export revenue by product.

- These illustrative impacts are not trivial and could be material for smaller sectors. But neither are they particularly large relative to our total goods exports to China of $20 billion or our aggregate exports to the world of $63 billion.

Opening up new trade opportunities is the most meaningful way of supporting optionality for exporters

- New Zealand’s high exposure to the Chinese market has delivered exporters significant benefits. But such exposure comes with obvious risks too. If the Chinese economy slows materially or barriers are imposed on New Zealand exports for any reason, some exporters will face challenges.

- Calls to diversify New Zealand’s export profile have become louder since our last report. This is fine in theory, but difficult to achieve in practice.

- Individual companies assess risk and make decisions based on many factors, including selling into markets with existing customer relationships and which provide the greatest returns.

- New Zealand’s aggregate exports to China represent the sum of thousands of individual business decisions. Who determines which companies should export which products to China, and how much is too much?

- Our trade negotiators are working hard at opening up other markets for New Zealand exporters to give them more options, most notably via the UK and EU at present. This is the most meaningful way of supporting optionality for exporters.

- Our scenario modelling indicates that the ability to redirect exports to other markets reduces the overall economic costs of hypothetical disruption to the China market for any product. Investing resources in these alternative markets to deepen commercial relationships would seem to be a prudent option. The ability to pivot production toward different products will also enhance New Zealand’s trade resilience.

This is the Executive Summary of a Report prepared by Sense Partners for the New Zealand China Council, updating where the New Zealand-China trade relations has moved to. The original Report includes Notes. It was funded by New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, New Zealand International Business Forum, ANZ Bank, the North Asia Centre of Asia-Pacific Excellence and MinterEllisonRuddWatts.

16 Comments

at the end of day, the EU will keep relying on Russia's energy, and NZ will keep relying on Chinese market, and relying on Chinese technology in near future if not already.

is there a point to fight against trend?

I would have thought the situation unfolding in Ukraine and the European economies having to pivot away from Russian energy is a great example of why one should fight against that trend.

Oh poor Xingmo, Chinese technology is largely copied or stolen from the west.

Pity the FTA with India seems to have stalled. Talking about dairy pivoting into other products, surely NZ Ghee would be happily snapped up at a premium by India's elite!

To a large extent, the products we send to China are unlikely to find markets in India. As the report says, in relation to India "hope springs eternal" but the challenges are very great. Lots of failures and few successes has been the NZ history of trying to develop exports to India. And there are good reasons for this.

KeithW

This is an excellent report and the full report is well worth downloading.

However, I tend strongly to the perspective that the report underestimates the challenges of diverting products elsewhere as a result of using a greatly flawed Treasury generic assumption that the price elasticity of demand is only -0.2. Price elasticity varies greatly between products and for key products including milk powder, lamb, mutton and timber, the market would totally crash without China. In contrast, some other product such as beef and cheese could be more easily diverted, albeit still at considerably reduced prices.

KeithW

I concur,navigating the tension between our trading reliance on China with escalating geo-political tensions will require exceptional diplomacy.

As an aside, it's hard to take Australia seriously when on one hand they relentlessly bluster on coming millitary conflict with China while simultaneously exporting >40% of all trade to CHina including the very resources China require to create the millitary infrastructure required.

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/reality-of-our-time-dutton-warn…

I agree with you Te Kooti, I have always maintained that we have to walk a fine line with China as there is no one to take up the economic slack if we lose them as a buyer of our primary goods.

It is noticeable in the graph provided that the countries with substantial exposure to particular markets were exposed to largely democratic customers , as opposed to our exposure to an autocratic market which has proven belligerent to others recently. So arguably our risk by the nature of our customer in China is higher. As for technology we are better to look to other western suppliers who are less prone to spying or using that technology for their own ends . So yes there is a multitude of good reasons the trend is not our friend.

I believe that with China it is totally inevitable that sooner or later we will reach the same point that we are with Russia. Just look at the situation now. Despite their ambiguous rhetoric and prevarication, they basically support Russia and their actions, and through intermediaries are providing military support. Read their media. The tenor of their coverage is that basically they support Russia's actions and their only concerns are how it may affect them commercially and their intentions re Taiwan. Their political and economic aggression is blatantly obvious and their military aggression is barely cloaked while they are increasing their capability and strength. We are fools if we increase our dependence on them any further because that is a noose that they will be very willing to tighten when it suits them as they have amply demonstrated in Australia. Our urgent task now is to reduce our dependence on them as quickly as possible without precipitating a negative reaction from them. i.e. respectfully and politely back away from them as fast as we can, and when far enough away, run like hell. Any NZ business which is dependent on China and is not thinking like this will face the very real risk of going broke when the inevitable confrontation occurs.

We need to be very careful not to fall into the trap of rationalising to preserve the status quo. The example being all the Jews in Germany who did this and did not heed the obvious warnings and get out while they could.

More than 90% of Australia’s fuel imported – leaving country vulnerable to shortages, report says

What diversification is NZ undertaking to ensure fuel supplies beyond nations which support and do not sanction Russia - I am thinking of OPEC + in the first instance? Surely China and Russia are major decision makers in this process.

Chris, we trade with China because it's in our own best economic interests to do so and there is nothing wrong with that. There is line we must defend but is it Ukraine or will it be Taiwan? Where is the point that we voluntarily reduce our standard of living and send our young men to die on foreign battle fields? I was at our family Urupa a week ago and it has a number of 28th Battalion buried there. It is sobering.

The older I get, the more cynical I get. Less than 20 years ago the US/UK invaded a soveriegn state based on fabricated evidence with the loss of 200,000 civilian lives in the process. The Ukraine invasion suits both the UK and US regimes as it distracts from the domestic ineptitiude of both leaders and they are in the business of war.

Ukraine is fast becoming a proxy war with Russia using Ukrainian soldiers, hence the enthusiasm the west is supplying them with better equipment to weaken Russian military , however there will be an inflection point where Russia will fight back and then the west will need to be very careful we don't end up in WW 3 .

Yeah but were to from here Fairyfrank, we may as well take Putin head on now or wait for the inevitable. This should have been learnt from the Hitler saga.

No fairy's here hans . I think the Ukraine war will come to stare down between Putin and the west to see who buckles first it will be very nerve racking for all teetering on the brink , there has been report's of Putin having Parkinson's disease for quite some time and recent footage of him having tremors etc seems to give it some credence. While I couldn't give a stuff about his health if he does have it he has got nothing to lose which makes him very dangerous.

Sorry frank didn't mean to spell your name wrong. I totally agree with what you say but the west can't take a backward step now. Lets hope Putin drops dead.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.