By David Mahon*

When exercising authority, start sternly and then exercise leniency.

If you start leniently and then become stern,

People will resent you …

Hong Zicheng, Daoist, 16th century CE

Economic reform in China has been a constant feature over the last forty years, but some government initiatives have appeared counterproductive to the market forces that have driven China’s economic evolution. Reforms can manifest as loosely governed experiments sometimes leading to surging growth, but also containment and consolidation, which have often been misinterpreted by the West as communist recalcitrance.

The idea of a prevailing ideological struggle at the heart of China’s political and economic planning is a misinterpretation of Chinese political culture. The Chinese Government knows there is no alternative to a market economy, but one qualified by greater degrees of intervention and planning than in American and European economies. It has learned much from its economic management mistakes over the past four decades and tends not to repeat many, but it remains deeply haunted by those that have sparked social unrest in the past.

The demonstrations in Chinese cities in 1989 were triggered by hyperinflation (28% in late 1988 and into 1989). In the late 1980s the Chinese leadership was following the advice of Western institutions, particularly the International Monetary Fund, which encouraged the swift abolition of price controls, and a core of Chinese policymakersthought only rapid change would free China from its command economic past. The carnage that ensued after people took to the streets in their millions, initially to protest the consequences of economic shock treatment but later including varied causes such as greater political representation, so shocked the government that it will now pay almost any economic price to avoid such chaos. The Chinese Government has still to learn how to intervene in a timely manner when bad policies threaten stability. It tends to act too late.

China became the centre of global manufacturing in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and importing and exporting became key drivers of reform, but these were poorly governed and often facilitated corrupt practices. As long as Chinese factories drew workers from the overcrowded fields and villages to burgeoning industrial centres, and prosperity grew, trade irregularities were tolerated. By the turn of century, the corruption and inordinate empowerment of smugglers, influence peddlers and their political backers threatened social and economic stability in some sectors.

We were investigating the live lobster trade from New Zealand into China in the late 1990s. Ninety percent was sold legally to Hong Kong but then smuggled through Chinese ports, all controlled by four family companies in southern China. I was cornered in a warehouse at the back of a wet market and told I would be beaten up if I did not stop asking questions about the smuggling. The smugglers were making an enormous margin, so the incentives were significant. With the tensions with Australia now, a lot of lobster is being stopped at ports again, and the smugglers are back.

Foreign consulting firm employee

In the late 1990s, the central government warned a crackdown was coming and most smugglers of products such as seafood, alcohol, computers and iron ore switched to legitimate practices. Those who did not were arrested and many sentenced to long prison terms. Trade was generally not disrupted and officials, a few of whom had made small fortunes working with former criminals, swiftly became zealous enforcers of customs regulations, taxes and tariffs.

In more recent years, warnings were given, and subsequent campaigns waged against shadow banking, polluting factories, illegal conversions of agricultural land to industrial and residential use, and worker exploitation. The Chinese ‘socialist free market’ is in many ways a market struggling to apply effective rules, often belatedly and clumsily, but rarely different than in other developing economies. In China, however, the leadership has an uncommon capacity to accept economic losses for the sake of market and social stability. Its COVID management has been an example of this. COVID was also an opportunity for the more statist inclined Chinese officials to empower government owned assets at the expense of the private sector, which has largely not occurred.

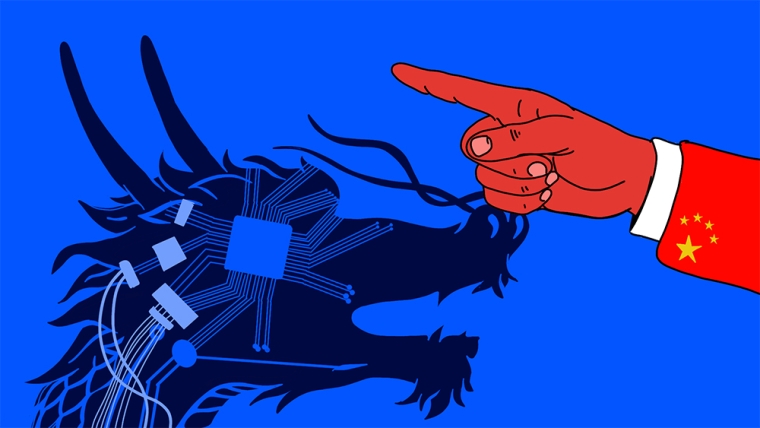

The current tech company crackdown is not an assertion of state control over a profitable sector out of some need for competition, but a long overdue attempt to bring stability and accountability to a critical part of the economy. It is fanciful to imagine that a president as powerful as Xi Jinping would feel threatened by any high-profile billionaire. Chinese businesspeople do influence local officials profoundly at times, but they do not ‘own’ senior politicians to the extent found in many political cultures where politicians’ careers are facilitated through extensive private and corporate funding.

Tech robber-barons

The government fining Alibaba RMB 18.2 billion (USD 2.8 billion) for violating China’s antitrust laws, and suspending the phone app of ridehailing firm DiDi while investigating its use of customer data, are attempts to contain these companies’ monopolistic and social influence. Not only do these two firms stifle innovation in their sectors, they also possess vast databases of customer information, and therefore the means to manipulate individual thought and behaviour. The latter is the jealously guarded domain of any government, but particularly one as authoritarian as China’s.

The Chinese Government also knows it needs a competitive technology sector if it is to achieve the levels of domestic innovation upon which its economic future and national security depends — particularly when Washington is doing all it can to block China’s technological development. The present campaign is not primarily a crude assertion of state power over the potential political power of technology robberbarons. The Chinese state clearly intended that political consequence, but the larger motive was to implement anti-trust legislation and facilitate a more dynamic, innovative technology and service sector domestically.

Fighting intellectual infanticide

Private tuition companies have also been the target of Chinese regulators recently, not because they are monopolistic, but because they are products of the failures of the Chinese state education system. China’s online education market was RMB 454 billion (USD 70.25 billion) in 2020. The private tuition sector exists because the schools do not impart enough in the day to equip children to secure scarce places in good universities. The need for extra tuition at night creates inordinate stresses on Chinese students and their families.

The government has been responding to middle class anger, but in the short term has made the issue worse. In this crackdown, the Chinese authorities have taken away facilities that were giving many children the competitive edge needed to qualify for tertiary education and created even more pressure on Chinese households, forcing parents to step back into the nightly drudge of administering extra tuition. With so few places in good universities in China, it is hard to see the swingeing national examination system changing soon.

The cost and stress of helping one child through their education is such that birth rates will not rise until this is resolved. The core and structure of Chinese education itself needs reforming. It is one of Xi Jinping’s aims, but as in medicine, dealing with symptoms rather than root causes can often prolong suffering.

Recovery and caution

The technology sector will recover its equilibrium and much of its value soon. Alibaba will adapt to the constraints being placed on it, while remaining a strong, innovative company. Despite some excesses in its financial businesses, Alibaba has striven to maintain ethical standards amongst its employees and strong principles of service to its customers. It has been a trailblazer in the creation of e-commerce and cashless transactions, not just in China, but throughout the world. Ride hailing firm, DiDi appears little affected operationally, despite new subscribers being unable to download the DiDi app.

My work is the same. Most people already have the DiDi app and just as many use the other apps to book us. If the government controls this company a bit more it may mean our working conditions improve. You can hope, right? If they screw it up, another company will appear, and I will work for them. In the end we are all really self-employed.

Beijing DiDi driver

The education-tuition sector will not recover as quickly or deliver similar returns as in the past once it stabilises, for the Chinese Government is determined to reform state education and reduce the profit motive in the private tuition sector. Fully registered private secondary schools are different, for they offer examples of best international practice from which the state can learn.

In all these recent instances of government intervention, there is a common denominator that foreign investors should have been considering more deeply over the last five years. The Chinese Communist Party will resist any challenges to its political and social power from private companies, and it will also filter and manage content, whether it is in school exercise books, films, or on social media platforms. This is not a threat to the foreign and private domestic firms that make up 90% of the economy, as few will even graze these domains. It is companies of scale that trade information across platforms and offer media content, and in Alibaba’s case, consumer credit, that risk censure.

Whenever a sector is booming, investors should stand back and see how rapid growth may relate to political sensitives and operate within the existing constraints of Chinese regulation, before investing for the medium or long term.

China will attract strong foreign investment in the coming years as the underlying economy is sound and the returns attractive. The Chinese Government is not hovering at the edge of each burgeoning sector ready to nationalise commercial successes, but it is ready to marginalise what it perceives as companies operating beyond the state’s social controls. These risks can be quantified, and there are grounds for confidence that the government can balance social control with a level of freedom that market operators require. But foreign investors must not ignore the need for social and political due diligence alongside financial and corporate due diligence.

*David Mahon is the Executive Chairman of Beijing-based Mahon China Investment Management Limited, which was founded in 1985. This article was first published here and is reposted with permission.

23 Comments

I would hope NZ has equally competent leaders to it a better place.

zing,

Isn't it wonderful to have the freedom of expression you have here? Not that we are perfect, very far from it and there are areas in which our right to free speech is under threat. However, belonging to the Free Speech Coalition is not going to see me arrested.

China has the right to govern itself as it wishes, but I far prefer our very imperfect democracy.

A bit wrong there. When tackled on the question of free speech in China their president quickly retorted that there was no issue at all with free speech in China, it was only after speech that you might not be free.

It's like eating lava. You can eat lava but only once.

Or as per Mae West - you only live once, but if you do it right, once is enough.

Competency as one of the most significant factors for my vote. However not quite as important as morality; so along with increasing productivity which is the only way NZ will become wealthier I'm concerned about the treatment of those who are severely mentally or physically ill. And above both economic competence and kindness I'm most concerned about accessing the information needed to make judgements about those two factors. Along with my daily newspaper and various news outlets both on TV and online I read Interest.co.nz looking for challenging opinions.

I would hope NZ has less autocratic and dominant state leaders to help it to a better place.

You're not going to win the crowd in a free democracy over by offering them more control and fewer rights.

I first met David Mahon in Beijing in 2008. Ever since then, when one of his newsletters arrives in my Inbox it is always immediately opened. For Westerners, trying to understand China is very challenging. My Chinese friends tell me it is also challenging for them. As one part of trying to put the big picture together, I always find David's insights to be valuable.

KeithW

His recent pieces have been much better. At one stage his pieces lacked balance and he seemed quite biased towards our 'Chinese fiends', Haha sorry couldn't help myself.

My personal analogy is always China tries to be an XXXXL sized Singapore. In that sense, Singapore can always give western audiences some cues.

That's because Lee Kuan Yew chided Deng Xiao Ping which the latter took it as personally to prove what China can become.

particularly when Washington is doing all it can to block China’s technological development.

On what grounds is the US justified taking this unilateral action and for whose benefit?

America first. Exceptionalism.

To understand China, start by being a Chinese.

i saw an analogy saying for the west to understand China is like for the two dimension beings to understand three dimension beings.

To learn something new, one has to unlearn everything he knew and leave his prejudices behind.

hmmm

like the Taosim says ...

Don't the communists hate taoism?

Chung Kuo Wan Wan Sui ?

Check it out. The most cooked in the head bromance I’ve seen in a long time :D

xing,

Chinese exceptionalism is no more justifiable than American exceptionalism or indeed the British version when they were the world's Great Power.

key words here: not to be irreverent!...is that correct Jack Ma?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.