The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the transition to a digital economy, which will hold the key to future growth and opportunities. That is why, as we prepare for the post-pandemic era, we must acknowledge that the digital economy’s potentially limitless benefits will not be equally distributed unless we take the right steps now.

Mobile devices, the internet, cloud computing, and other innovations have created a hyper-connected global space in which billions of people can work and pursue more dynamic ways of life. Digital platforms have changed the way we consume, work, and create economic value, and digital assets such as computers, communications equipment, and software have helped firms reduce production costs and enhance efficiency.

The digital transformation will continue to accelerate with the wider adoption of big data and the convergence of Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies such as 5G, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things. Already, a McKinsey Global Survey finds that the pandemic has led businesses to accelerate “the digitisation of their customer and supply-chain interactions and of their internal operations by three to four years.”

But the question is whether the benefits of this acceleration will extend beyond businesses to workers and consumers. By making old technologies, processes, and even entire industries obsolete, digitalisation will continue to cause job losses. The World Economic Forum’s 2020 “Future of Jobs Report” predicts that many private companies will employ machines and algorithms more broadly than ever, hindering employment prospects across sectors and regions. AI, robots, and other new technologies could threaten 15% of the average company’s workforce as soon as 2025.

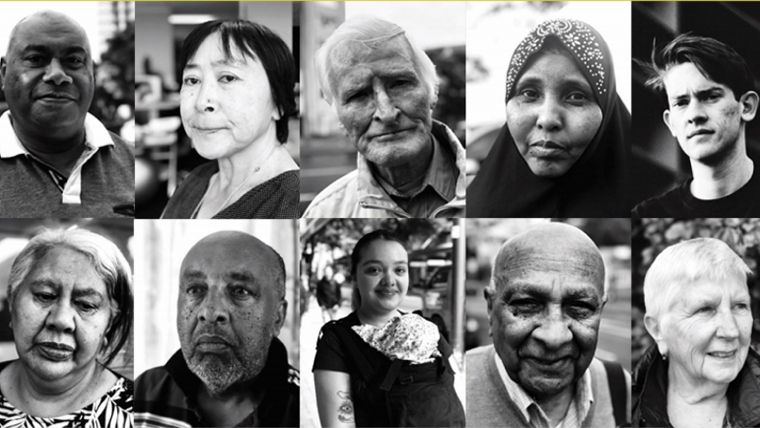

Given such effects, the digital transformation could widen social and economic disparities and expand the wage gap between digitally skilled and unskilled workers. There is already a deep divide between socioeconomic groups and across regions when it comes to access to new digital technologies, and technological diffusion will be uneven across firms and industries as well. Small companies may have less capacity to adopt new innovations than larger ones, which in turn may try to block new competitors from entering the market.

More broadly, it could take some time for the digital revolution to drive economy-wide productivity growth. Economists have long observed the “paradox” that the impact of information and communication technologies shows up “everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Now that the pandemic has widened the productivity gap across firms and industries, traditional companies and small businesses may be slow to recover, while the tech giants flourish under conditions of heightened digital demand.

The digital revolution also raises political concerns, such as when governments and corporations misuse data and technology. During the COVID-19 outbreak, some East Asian countries used contact-tracing apps, mobility data, cameras, and other digital technologies to contain the virus, but this surveillance often came at the expense of privacy. With the tech giants wielding such massive power through their command of user data, consumers are becoming more aware of the importance of data security and privacy protections.

Addressing such questions is essential to preparing for the post-pandemic era, when all countries will need to embrace new ways of working, producing, and consuming. Digitalisation can make a huge contribution to public health, the environment, consumer welfare, and wealth creation across society, but only if the public and private sectors work together to ensure inclusiveness.

Most countries will need policies to narrow the gaps in digital skills and access, because a growing share of jobs will require more technological know-how. Education systems must do more to equip students with the knowledge and skills they will need in a digital future. And job training must keep all workers up to date on the latest digital technologies.

Governments have a critical role to play on all of these fronts. It was state support and commitments that brought us revolutionary innovations like the internet, antibiotics, renewable energy, and the mRNA technology behind the development of the most effective COVID-19 vaccines. To fulfill their role as market makers, governments need to increase investments in physical infrastructure and human capital, and provide financial and tax incentives to ensure equitable access to critical technologies. They should also be exploring ways to provide more grants, subsidies, and technical support for small and medium enterprises and start-ups, so that the benefits of digital revolution do not remain limited to a few large companies.

When it comes to Big Tech, in particular, the rules and standards of the pre-digital economy no longer apply, which means that most countries will need to update their competition policies and regulatory frameworks to ensure free and fair competition. And along the way, they should establish clearer rules and standards for data security, digital ownership, and user privacy.

Ultimately, though, effective governance requires a global consensus. Different national approaches will merely fragment the digital economy and invite tax and regulatory arbitrage. Fierce competition between the United States and China over 5G hardware, social-network platforms, and semiconductors has led to nationalistic and protectionist measures, pointing to the need for a more multilateral, cooperative approach. The goal must be to devise a new system to manage the cross-border exchange of digital information and technologies, while creating stronger rules and standards for digital trade.

The world is still recovering from an unprecedented shock. But the sooner we prepare for the “new normal,” the better off we will be. And successful preparation will depend on whether we ensure digital inclusion.

Lee Jong-Wha, Professor of Economics at Korea University, was chief economist at the Asian Development Bank and a senior adviser for international economic affairs to former South Korean President Lee Myung-bak. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021, published here with permission.

2 Comments

Does the main message of the article lie in the second-to-last paragraph?

"Global consensus" is necessary for "effective (global) governance". So, as if we aren't

already slaves to "big tech", it seems we are being encouraged to accept the idea of more central, global control, sold as "inclusive" as "beneficial". I wonder if we'll have a choice in the matter?

Hilarious for these people to believe a person with onset dementia or severe learning issues will rapidly be able to learn and use new technologies as easily as they did. Perhaps they just like to disenfranchise and ostracize people with disabilities; that would explain most the banks closing branches and denying services to people with disabilities.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.