In early April I spoke to the New Zealand Farm Forestry Conference in Napier about farm forestry options as I saw them. Most of the farmers I was talking to have had many years of experience in farm forestry, so I was certainly not going to tell them how to grow trees. Rather, I explored how to find a pathway through some of the challenging and at times imponderable issues that farm foresters currently face.

Many of my forestry presentations have focused on flaws in the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS). This presentation was different. I simply took the rules as they are and looked at how farm foresters could best respond in their own interests, be they economic interests or broader issues coming from the heart.

My starting point was to briefly look at the journey New Zealand’s production forestry has taken in recent decades. I used three graphs published in November 2023 in a USDA GAIM Report, where GAIN stands for Global Agricultural Information Network. GAIN reports are a great source of current and historical facts with no political messaging.

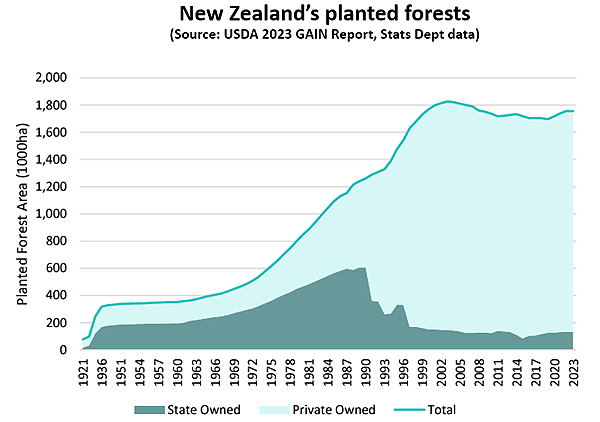

The first graph below demonstrates two key points. The lower dark-coloured area shows how New Zealand production forests were sold off in the 1990s from public to private ownership. The upper light blue area demonstrates the big uptake in forest planting in the 1990s.

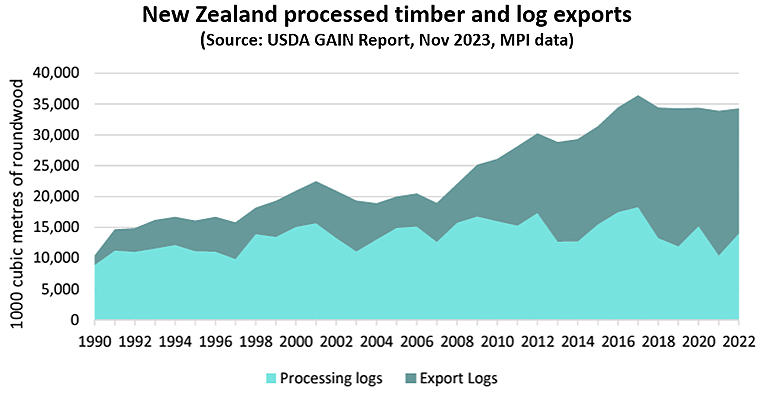

The second graph demonstrates that processed-wood volumes have bounced around but there has been no overall growth in recent years. In contrast, the log trade has grown from almost nothing thirty years ago, reaching a maximum in 2023. What the graph does not show is that export volumes are declining this year. This is not because there is less timber to be harvested, but because decreasing returns and increasing costs mean that the economics of harvesting no longer stack up on land that is steep or distant from ports.

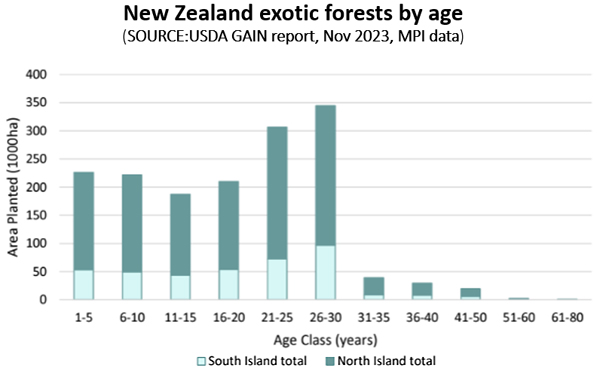

The third graph demonstrates the wall of wood aged 26 to 30 years waiting to be harvested from the big plantings in the 1990s. if it were not for economic issues that threaten harvest operations, the next five years would see more exports than ever before.

I then observed to my audience that timber is where we are more dependent on China than for any other export product, with almost 90 percent of log exports going there. I also observed that China now has less need for our timber than in the past. This is in part because China’s big infrastructure years are now behind us. Our logs are largely used for concrete formwork rather than products with higher value-add.

New Zealand is now the only country that exports significant volumes of softwood logs to China. Countries like Russia now only export lumber, not logs. Also, China is becoming increasingly self-sufficient in timber, with big eucalyptus plantings in the south of China. However, China’s timber markets are obscure and it is hard to confidently take an overall positive or negative stance about the future.

I then looked at the economics of sheep and beef farming relative to various farm-forestry options.

There is no doubt that most sheep and beef farmers are doing it tough right now. Profits in the last 10 years have typically been in the range of one to two percent return on capital and slipping below that in the last three years. Right now, many farmers are cash-flow negative, with land values also dropping precipitously.

This also means that many farmers lack cash right now to convert some of the rougher country to trees.

When preparing the talk to farm foresters, I ran lots of spreadsheet models of net present values and internal rates of return for various production forestry scenarios. The big message was that using prices and costs from two to five years ago told a story of nice returns for radiata pine. But that story now belongs to history. Looking forward, the big message relating to production returns is lots of uncertainty and high economic risk.

This aligns with the current attitude of the big forestry companies. Whereas until about 18 months ago there was a mad dash to buy land for its potential timber value, that interest has disappeared. Almost no-one is interested in buying land for production timber by itself.

I then looked at what happens if land is developed out of pasture for new radiata pine production based on harvesting at 25-30 years and at the same time earning carbon credits through to 16 years under the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS)) averaging regime.

I used a conservative price of $60 per tonne of carbon (NZU) whereas the minimum prices for which the Government currently auctions carbon is $64 this year, with this price having been officially set to rise in each of the coming years.

In doing these calculations, I used the official look-up tables for radiata pine growth in different parts of New Zealand. These tables are used for assessing carbon credits for all forests of less than 100 ha and are generally considered to be conservative. Forests of more than 100 hectares are measured on actual growth.

The big message here was that carbon credits are the business to be in if converting pasture to trees. They can rapidly turn a likely unprofitable timber-production business into a profitable dual business. It did not matter what scenario I looked at, as long I used a carbon price of $60 then the internal return was acceptable, and in many cases much more than acceptable. In a typical example, it raised the IRR from around 2% to about 9% even with these low carbon prices and an inbuilt land value. It also brought the payback period including land value as a cost back to around ten years or slightly less.

These projected returns raise questions as to why the big investment companies are not doing this right now. The most important reason is that confidence has been knocked around so much over the last two years, with Governments changing the regulatory rules of the game multiple times, that commercial investors lack confidence that the rules won’t be changed again. Forestry is a long game.

I then looked at growing so-called permanent forests, where new forests are registered in the permanent scheme and then not harvested for at least 50 years. I compared this to two cycles of production timber harvested at 25 and 50 years combined with carbon credits under the averaging scheme limited to the first 16 years.

The results showed that both systems were profitable but the economics of the permanent scheme were superior under almost all realistic scenarios that I could envisage. Of course, pine forests can grow for much more than fifty years. There are radiata pines in the Wellington Botanic Gardens that are more than 160 years old. They are believed to be the first radiata pines ever brought to New Zealand

Some farm foresters are not keen on the idea of non-harvested pine forests. The reasons are generally unrelated to economics. Also, some farm foresters, who have been committed to both production and environmental forests for much of their lives, are suspicious of the whole concept of carbon farming.

Subsequent discussions went on well into the night, as we not only talked about radiata pines but also discussed eucalypts, redwoods and poplars. Within the farm forestry association there are groups of farm foresters strongly supportive of each of these other introduced species and with sound reasons developed from experience.

My own perspective is that all of these other species are underutilised within the New Zealand forestry landscape. I plan to say more about them on the coming months, and what we need to do about this.

There is also the issue of indigenous species and the role they can play. I had long discussions about this with both nursery providers and farm foresters, including the monumental issue of establishment costs. Many of the farm foresters are absolutely committed to using indigenous species, particularly for riparian plantings, but the cost of establishing indigenous woodlots at scale is so much more than for introduced species. Also, the introduced animal-pest species absolutely love indigenous trees. Introduced species are much more pest resistant.

The biggest message from all of this is that carbon credits lie at the heart of forestry economics. But it is not a simple story.

*Keith Woodford was Professor of Farm Management and Agribusiness at Lincoln University for 15 years through to 2015. He is now Principal Consultant at AgriFood Systems Ltd. You can contact him directly here.

17 Comments

I remember hearing a wise and successful businessman say something along the lines of:

Never embark upon and enterprise that relies on government policy - it can change at anytime.

However having said that, I am growing trees for carbon credits - but realise that the future income stream is by no means certain

Thanks Keith.

I feel NZ missed a golden opportunity when we went down the radiate path rather than the eucalyptus path. In that pine needs alot of harmful treatment to be used were as eucalyptus in some species can be sat straight on the ground and won't rot. They grow quick etc. Yes they do have a habit of falling over when a good blow is happening. Be good to read your future articles on them and redwoods. From my understanding our hole system from milling to grading these species is not there.

I went for eucalypts and macrocarpa - and have no regrets. If you leave the edge trees, they don't fall over. Both are best left growing for 50-70 years - longer than the usual short-term-return window. Same with most species.

As for credits, I've said this before; you can't pull yourself up by your bootlaces, and you can't 'make money' from a 'sink', unless someone somewhere else, commensurately isn't. And the resistance is strong...

I made the mistake of planting euc.nitens. in our warmer climate they only last 15 years, then become susceptible to rot and insect damage. By that time they are 20 meters high, so a drama to drop. Apparently it is best to coppice them every 5 years or so. My other eucalyptus are doing well.

Had some E nitens that blew over milled along with some pine and fir. Thought I'd make raised garden beds out of them. I didn't expect the timber to last, but I cut a lifetimes worth so durability didn't really matter.The timber looked great coming off the mill. Really heavy to handle though. It's been stored in the shed for a couple of years and while I've heard of nitens having a problem with collapse, I didn't expect my 6 metre 150x50 planks to suffer as badly as they have. Definitely a firewood tree! Shame, I have inherited a lot of the things. I have tried 3 other Euc sp and would like to try more, but the advice I got was my place has rainfall, frost and wind limitations for the most useful types.

Our Farm in Taupo was situated in the best spot in NZ for growing E Nitens but they also got that bug. But there are hundreds of different Eucalyptus that could have been developed some for furniture some for framing etc rather than just used for boxing if we are looking at value added Eucalyptus had more potential.

When I built a house twenty plus years ago I used a small amount of Saligna and a rooms worth of Fastigata(?). I also used a heap of second hand native, tawa, rimu, matai and kahikatea.

The eucalyptus was ok but the weight and shrinkage was a complete pita. I'd use again but only because the natives are so hard to come by. Tawa flooring was excellent and matai for bench tops and stuff. Natives were so much more workable, incredible what we lost by clear felling/burning everything.

Eucs are too prone to windborne pathogens from our Aussie neighbour. A risky bet. They have thrived in introductions in the tropics but we are just too susceptible - living downwind + main trading/biosecurity partner.

Radiata thrived because it was resilient to disease when compared to the 100's of other species that were trialled by our forefathers.

Monterey Pine when first brought to NZ is not the same Radiata Pine it was back then due to for a word genetic modification. So imagine if NZ govt way back in the 50s rather than invest the resources they did into Pine they had into eucalyptus, or another species Ifeel would have been a better out come all round

Profile is right - be very careful venturing into other species. Research all the work and study that has been done over the past 150 year and why we have ended where we are. I'm not anti other species (just put in a Saligna floor and joinery in a new house and its great) but the economics and other risks need to be carefully understood and realize a lot of this stuff has been tried before and failed.

Excellent piece Keith, looking forward to hearing future instalments. Particularly relevant for me with a 30 year old radiata plantation. Harvest economics not great, ETS too uncertain. Would very much like to extend native planting but establishment costs very high as you note

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.